By FRED KAPLAN

In 2010, the Cold War had been over for 20 years, and superpower tensions seemed a figment of the past. President Barack Obama’s “reset” policy with his Russian counterpart, Dmitry Medvedev, was spurring major initiatives in cooperative diplomacy. Obama’s “pivot” away from the ancient conflicts in the Middle East to the dynamic opportunities for commerce and peace in the Pacific seemed promising. Threats to our security came less from rival nations than from shadowy terrorist groups, which our former rivals opposed as well. The few wars we were fighting involved local insurgencies and hadn’t metastasized into the wider proxy battles of earlier times.

In 2010, the Cold War had been over for 20 years, and superpower tensions seemed a figment of the past. President Barack Obama’s “reset” policy with his Russian counterpart, Dmitry Medvedev, was spurring major initiatives in cooperative diplomacy. Obama’s “pivot” away from the ancient conflicts in the Middle East to the dynamic opportunities for commerce and peace in the Pacific seemed promising. Threats to our security came less from rival nations than from shadowy terrorist groups, which our former rivals opposed as well. The few wars we were fighting involved local insurgencies and hadn’t metastasized into the wider proxy battles of earlier times.

Now, as the decade roars to a finish, the world seems a very different place. Russia is once again a geostrategic foe. We’re locked in a trade war with China, whose expansionist aims—long a matter of concern—are clearer than ever. Regional conflicts, especially in the Middle East, are serving as chessboards for the competing ambitions of outside powers.

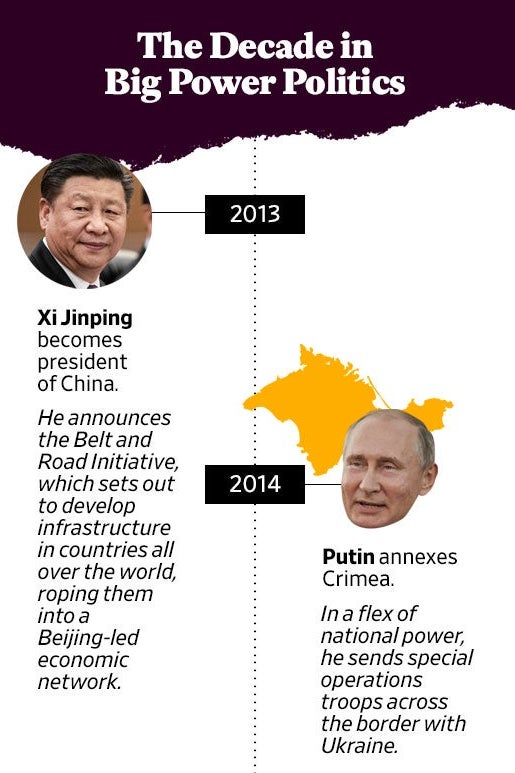

This transformation is only partly due to changes in leadership—Obama to Donald Trump, Medvedev to Vladimir Putin, China’s Hu Jintao to Xi Jinping. What’s happening, in a larger context, is that global politics are reverting to form.

Graphic by Slate. Photos by Fred Dufour - Pool/Getty Images, Sean Gallup/Getty Images, and Getty Images Plus.

When Putin invaded eastern Ukraine in 2014, Obama’s secretary of state, John Kerry, blasted the move not merely as immoral and illegal but also as anachronistic, saying, “You just don’t, in the 21st century, behave in 19th-century fashion by invading another country on completely trumped up pretext.” But, apparently, some countries do. Land grabs and power plays didn’t begin in the 19th century. (Read Thucydides on the war between Athens and Sparta in the 5th century B.C.) Nor, it seems, are they just yet relics of history.

What specifically caused the relative calm at the decade’s start to slide into turmoil? That calm, at least among the world’s big powers, was real. In 2010, Obama and Medvedev signed the New START nuclear arms-reduction treaty. Obama also persuaded Medvedev to cancel a lucrative contract to sell Russia’s most modern air-defense missiles to Iran—a move that stiffened the pressure on Tehran’s rulers to negotiate what became, five years later, the Iran nuclear deal. China seemed ready, at least in principle, to join in counterterrorism campaigns and to pressure its ally, North Korea, to stop developing nuclear weapons.

The chance of war with a major power seemed so remote that, for the first half of the decade, the U.S. Army suffered an existential crisis. Small-scale units, mainly special operations forces, were fighting insurgencies and advising allied militaries around the world, but the notion of large battles with tanks and artillery seemed absurd. Many serious officers wondered: What do we do with—and do we really need—a standing army of more than a half-million active-duty soldiers?

Then two things happened: Medvedev’s conciliatory leanings went too far, and Putin—who had stepped down from president to prime minister but had never fully relinquished power—stepped back up. A former KGB officer with a hankering for the glory days of the Soviet Union, Putin had long been nursing resentments over the West’s socioeconomic occupation of Russia and its shattered empire—the flood of Western companies, economists, and cultural artifacts—in the aftermath of the Cold War. President Bill Clinton had already gone too far in “enlarging” NATO right up to Russia’s borders. Ukraine, which Putin regarded as part of Russia, was drifting toward the European Union. Then, in 2011, Medvedev voted to abstain from, rather than veto, a U.N. Security Council resolution to condemn Libyan leader Muammar Qaddafi, one of Russia’s only stalwart allies in the Middle East. As a result, the West intervened and toppled Qaddafi, who, amid the chaos, was killed by rebels.

Putin ran for president again in the next election; Medvedev stood aside to let him win; and Russia, which had regained much of its oil wealth since the USSR’s implosion, set about rebuilding its military and cracking down on dissent at home. The Soviet empire was forever vanished, but Putin was determined not to succumb any further to what he saw as American-led imperialism. In 2014, after Ukraine’s pro-Moscow president, Viktor Yanukovych, fled Kyiv and Western-leaning politicians moved in, Putin annexed the Crimean peninsula—which Nikita Khrushchev had given to Ukraine in 1954. Soon after the annexation, Putin roused a secessionist movement in the eastern Ukrainian region of Donbass, even moving Russian forces across the border to help the rebels.

Both of those moves marked the end of Obama’s “reset.” They also cheered many American officers. The Army once again had a familiar mission. The NATO alliance, which was experiencing its own identity crisis (its new post–Cold War mission, to serve as a global expeditionary force, hadn’t gone too well in Afghanistan), returned its gaze to deterring and preparing for possible conflict in Europe.

Graphic by Slate. Photos by Saul Loeb/AFP via Getty Images.

The upshot was this: The United States and Russia could still carve out areas of mutual interest—arms control, counterterrorism, nuclear nonproliferation—but the two nations were never cut out to be partners. Their conflicts of interest—suppressed or submerged during the years of Russian weakness just after the end of the Cold War—were too numerous and too deep to avoid, and after a while, the tensions spilled over to diplomatic forums as well.

But this was not a revival of the Cold War. Neither the United States nor Russia dominates an entire sphere of the planet. Nor do their armies face each other, in vast garrisons, across a contested border. Putin has gained strength mainly by exploiting fissures within the West, most notoriously through the “information warfare” of influencing public opinion during elections.

China too has built up its power through nonmilitary means, stealing high technology from the West, infusing it into its own products, and selling them—while, at the same time, investing, mining, and manufacturing—around the world: in short, by pursuing a purely mercantilist foreign policy, which President Xi calls the Belt and Road Initiative.

Xi has also built up China’s air force and navy, not to conquer distant lands (he hopes his economic policies will do that), but rather as an “area-denial” strategy—i.e., to keep others, especially the U.S. military, from dominating the area around its borders. To extend the reach of its defenses, China has even constructed artificial islands in the middle of the Pacific Ocean and turned them into air bases.

In ordinary times, all this could have redounded to America’s benefit. Russia’s rumblings, earlier in the decade, roused European unity. China’s did the same with our allies in the Asia Pacific. Obama—like Clinton and the two Bushes before him—struck a balance, trying to lure Beijing into the global economy while containing its expansionist tendencies. In 2016, he and 11 other leaders negotiated the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a trade deal that would have solidified the U.S. alliance in the region and formed a bulwark against China’s unfair practices.

But Donald Trump has squandered these opportunities. In a way that has flabbergasted his own officials, alienated the allies, and filled our revived adversaries with glee, he has eviscerated America’s influence in the world.

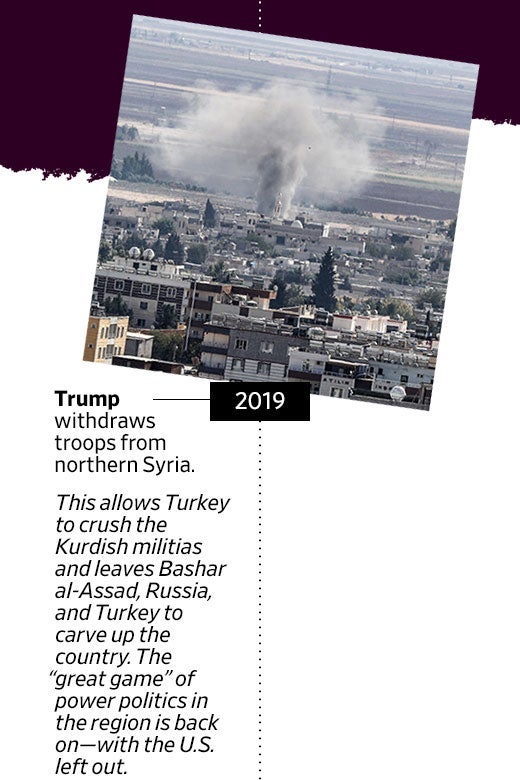

For reasons that no one has fully explained, he has often served Moscow’s interests: badmouthing NATO almost as intensely as any Kremlin commissar ever has, downgrading relations with Ukraine (even before the famous phone call with President Volodymyr Zelensky), and withdrawing the small contingent of U.S. troops from northeastern Syria. This last move allowed Russia to solidify its control over Syrian territory and set the stage for a power contest involving Russia, Syria, Turkey, Iran, and various jihadist and Kurdish militias that could intensify the region’s wildfires.

Graphic by Slate. Photo by Burak Kara/Getty Images

Yet for all his cooing over Putin, Trump has never come up with a strategy to leverage their putative friendship to America’s benefit. He could have worked out a deal to extend the New START treaty (which expires in 2021) or to tighten the accords struck in the early part of the decade to lock up loose nuclear materials. But Trump is hostile to any treaty that was negotiated by Obama. So we all must deal with the consequences.

Trump also did the opposite of exploiting the chance to cement alliances in Asia, not just in canceling the Trans-Pacific Partnership but also in launching the trade war against China, which has wound up hurting American farmers and manufacturers at least as much as it’s hurt China. (A tougher economic policy against China was justified, especially in fighting intellectual property theft, but wholesale tariffs are misguided; Trump seems unaware of the interlaced supply chain, in which many U.S. products contain Chinese parts.)

And, as with Russia, Trump has no strategy for competing with China—economically, diplomatically, or militarily. Meanwhile, Russia and China are doing all they can to extirpate themselves from the dollar-dominated global economy. (This will take years, but they’re off to a good start.) And large American companies, bereft of guidance from Washington and unable to do long-term planning in the face of Trump’s erratic tactics, are conceding to Chinese demands in order to preserve their bottom line. High-profile American emblems, from software firms to Hollywood studios to the NBA, are making these concessions. And the rest of the world watches; they see which way the wind is blowing.

So where does this leave us? The Cold War, which lasted roughly from 1947 to 1991, was a time of dreadful danger and destructive “small wars.” But it was also a system of international security, at least for the nations that allied themselves, by choice or by force, with one of the two superpowers. When the Cold War ended, that system broke down with it. The first two presidents of the new era, Clinton and George W. Bush, didn’t do much to create a new system. Bush and his team didn’t think they needed to: America was “the sole superpower,” and it would reshape the world in its image. That proved to be fantasy.

At the start of this decade, Obama seemed aware of the need to construct a new system, and Medvedev seemed a plausible collaborator in the project. But its foundations were flimsy. A new system would have required new rules on permissible behavior, new treaties of cooperation, maybe the drawing of some new borders or power blocs, and much more lavish spending—a new Marshall Plan of sorts—to foster security and stability in areas that were no longer protected by a superpower and that might, therefore, relapse into the territorial and sectarian disputes that gripped them in decades and centuries before.

None of that happened. It would have taken visionaries, the likes of which we’ve rarely seen, to make it so. Instead, as we enter the third decade of the 21st century, we see the old, familiar patterns and ploys of international politics—which John Kerry decried as “19th-century fashion” but which, in fact, date back to antiquity. Only this time, they’re unspooling in a world that is as hyperconnected and lethal and disorderly as any that’s ever been seen.

No comments:

Post a Comment