Announced in 2013, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI, also known as One Belt, One Road) aims to strengthen China’s connectivity with the world. It combines new and old projects, covers an expansive geographic scope, and includes efforts to strengthen hard infrastructure, soft infrastructure, and cultural ties. As of October 2019, the plan touches 138 countries with a combined Gross Domestic Product of $29 trillion and some 4.6 billion people.

Unpacking the Belt and Road Initiative

Supporting a diverse array of initiatives that enhance connectivity throughout Eurasia and beyond could serve to strengthen China’s economic and security interests while bolstering overseas development. At the first Belt and Road Forum in Beijing in May 2017, President Xi Jinping noted that, “In pursuing the Belt and Road Initiative, we should focus on the fundamental issue of development, release the growth potential of various countries and achieve economic integration and interconnected development and deliver benefits to all.”

The BRI is an umbrella initiative spanning a multitude of projects designed to promote the flow of goods, investment, and people. The new connections fostered by the BRI could reconfigure relationships, reroute economic activity, and shift power within and between states. In March 2015, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs disseminated an action plan (issued by the National Development and Reform Commission) that fleshed out specific policy goals of the BRI. These included:

Improving intergovernmental communication to better align high-level government policies like economic development strategies and plans for regional cooperation.

Strengthening the coordination of infrastructure plans to better connect hard infrastructure networks like transportation systems and power grids.

Encouraging the development of soft infrastructure such as the signing of trade deals, aligning of regulatory standards, and improving financial integration.

Bolstering people-to-people connections by cultivating student, expert, and cultural exchanges and tourism.

Beneficiary countries are likely to find the most attractive elements of the BRI to be its provision of hard infrastructure. Likewise, the BRI provides China with an opportunity to use its considerable economic means to finance these infrastructure projects around the world. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) estimates that the developing countries of Asia collectively will require $26 trillion in infrastructure investment to sustain growth.

Leveraging these needs against its economic strength may ultimately garner China significant political gains. Notably, many of the areas targeted by China suffer from underinvestment due to domestic economic struggles, and they often register low on the United Nations Human Development Index (HDI). Myanmar and Pakistan – two countries heavily targeted by the BRI – rank 148th and 150th globally in terms of HDI.LEARN MORE"Does China dominate global investment?"

To support the BRI, Beijing has injected massive amounts of capital into Chinese public financial institutions, such as the Chinese Development Bank (CDB) and the Export-Import Bank of China (EXIM). These banks enjoy low borrowing costs, as their bonds are treated like Chinese government debt with very low interest rates and they have access to lending from the People’s Bank of China, allowing them to lend cheaply to Chinese companies working on BRI projects.

This easy financing enables China’s state-owned enterprises (SOEs) to offer highly competitive bids for projects against foreign companies that might be more financially constrained. For instance, in 2015 Japanese construction companies lost out to their Chinese counterparts in a bid to build a high-speed rail project in Indonesia.

Discussing the reasons behind their choice, the Indonesian government cited Chinese financing from the CDB, which came with fewer strings attached. It should be noted, however, that the project has been fraught with problems. Critics have decried the terms of the contract, which has been revised several times since it was awarded, as unrealistic. Furthermore, contractors have yet to break ground on the railway due to licensing and land acquisition issues.

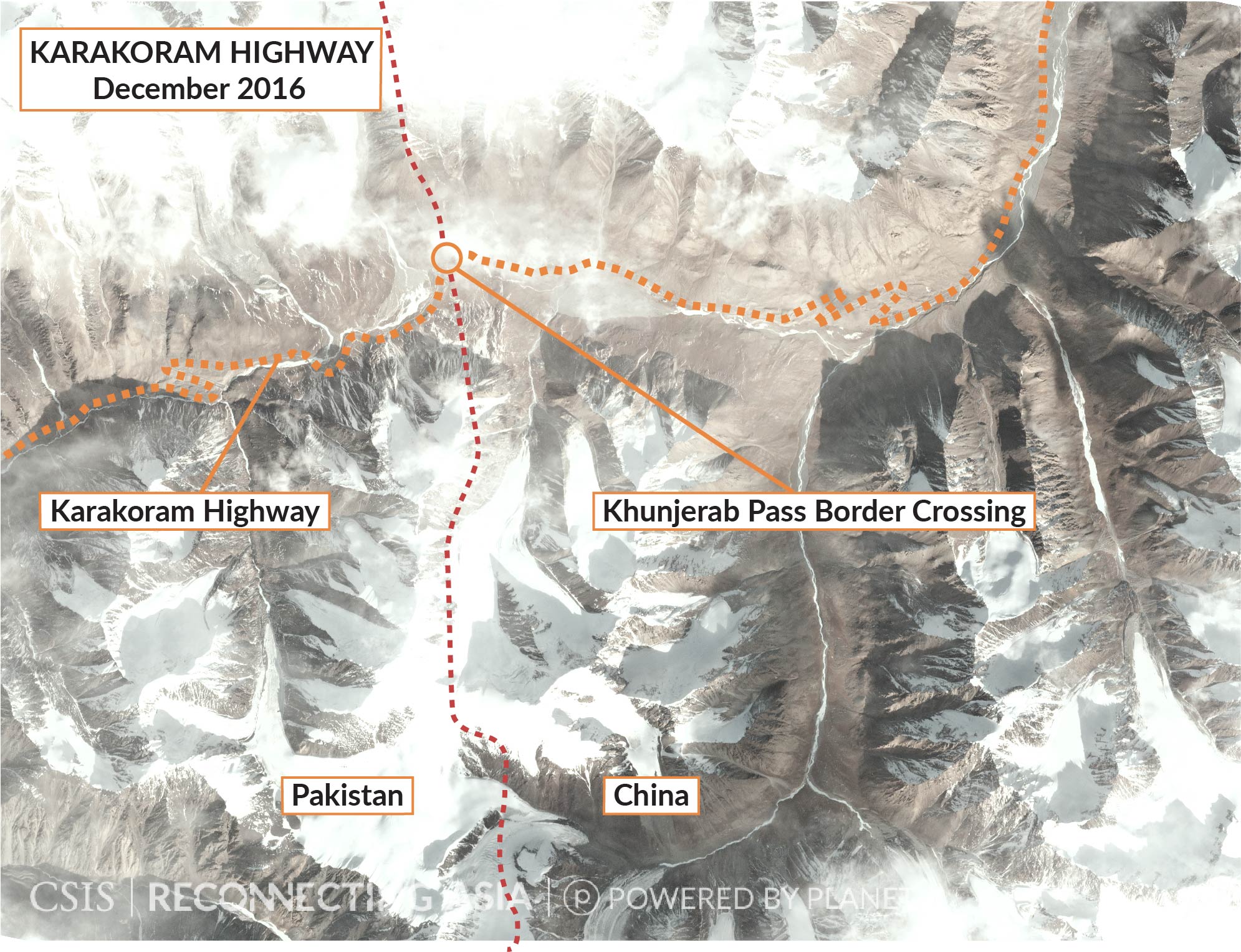

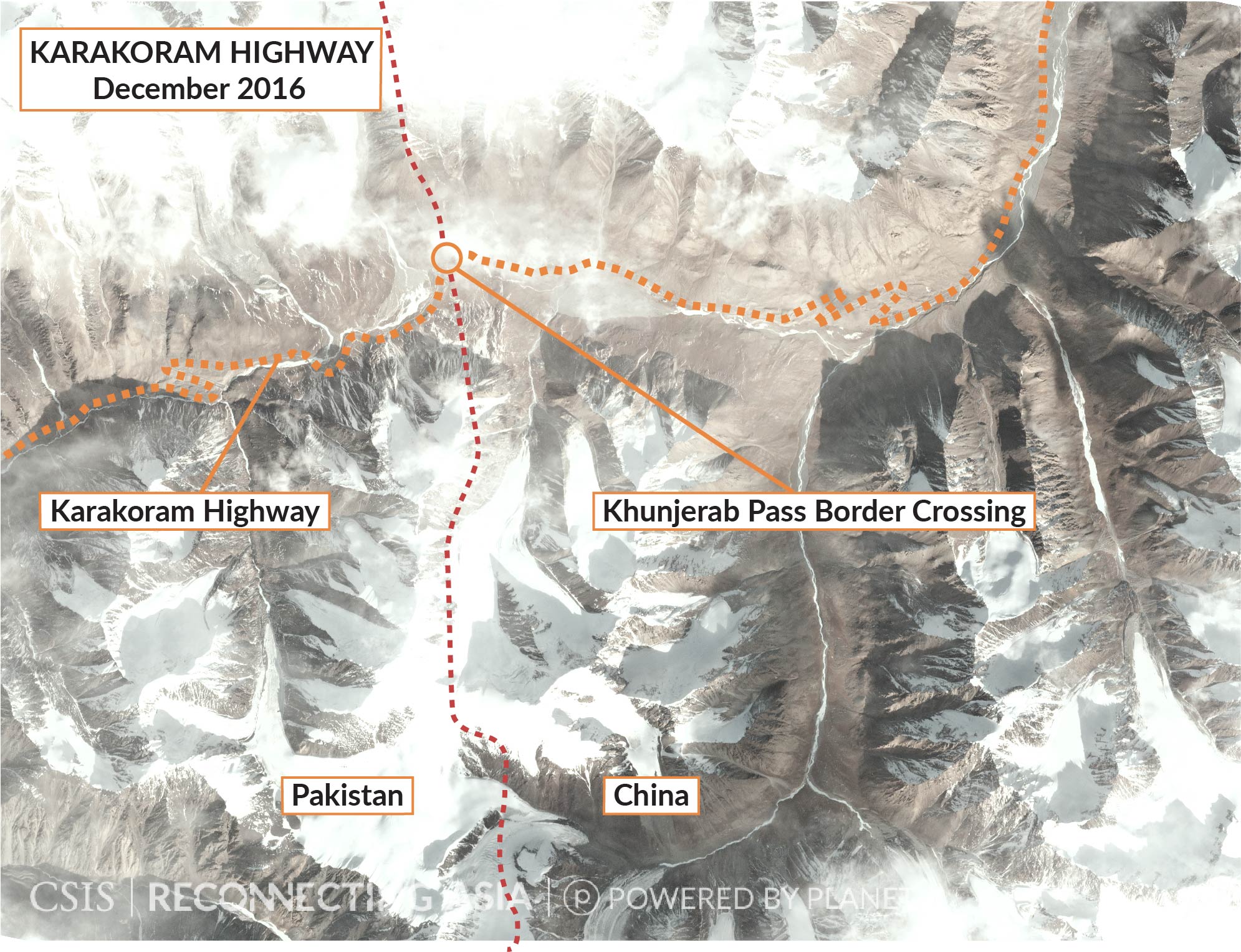

Some BRI projects are already underway, such as those associated with the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) – a 3000-kilometer corridor that runs from China’s Kashgar to Pakistan’s Gwadar. CPEC includes a wide array of infrastructure projects including highways, railways, pipelines, and optical cables, but more than half of the total planned investment for CPEC will go to energy projects like power plants. He Lifeng, Chairman of China’s National Development and Reform Commission, notes that CPEC is “an important loop in the larger chain of the Belt and Road Initiative, and would enable the possibility of a 21st Century Maritime Road.”

Pakistani leaders also view CPEC as important. In the face of a recent slowdown of CPEC projects due to geopolitical tensions, Pakistan Prime Minister Imran Khan took controversial steps in October 2019 to push forward the development of CPEC and provide tax exemptions for the state-owned Chinese Overseas Ports Holding Company, which operates Pakistan’s Gwadar Port.

CPEC is intended to connect the land-based Silk Road Economic Belt with the Maritime Silk Road, and Gwadar Port is an important part of this effort. It was leased to the Chinese Overseas Ports Holding Company from the Pakistani government until 2059, and is already being expanded. A highway from Kashgar to Gwadar has also been considerably upgraded. Further development projects of CPEC include the Gwadar Special Economic Zone, which is currently under construction next to the port and due for completion by the end of 2020.

How China stands to gain from the Belt and Road Initiative

The BRI has the potential to yield considerable economic and political gains for China. Many of these have been explicitly acknowledged in China’s official policy communiques, such as the expansion of China’s export markets, the promotion of the Renminbi (RMB) as an international currency, and the reduction of trade frictions like tariffs and transport costs.

Additionally, developing and connecting hard infrastructure with neighboring countries will help reduce transport times and costs. Establishing soft infrastructure with partner countries will allow for a broader range of goods to be traded with fewer regulatory hurdles. Raising capital for these infrastructure projects by issuing bonds in RMB will also encourage its use in international financial centers. In particular, China’s lower-income western provinces stand to gain, as the creation of overland economic connectivity with Central Asia will boost growth there.

Attendance at Belt and Road Forums

Forum (Dates)Number of Heads of State/Government1st Forum (May 14-15, 2017) 29

2nd Forum (April 25-28, 2019) 37Source: Various

Many of the potential benefits of BRI are less publicly articulated. For instance, some of China’s SOEs – such as cement, steel, and construction companies – have built up significant capacity (expanding factories and hiring workers) to serve the once booming domestic economy. As China’s economy has slowed, these companies are struggling to find productive uses for their resources. Similarly, China has a large reserve of savings that is not being invested productively. Investing in large-scale overseas infrastructure projects enables China to export its excess savings and put its SOEs to work.

If successfully implemented, the BRI could help re-orient a large part of the world economy toward China. Increasing the amount of trade, investment, and connectivity between China and countries throughout Eurasia will also render these countries more dependent on the Chinese economy, increasing China’s economic leverage over them. This may empower China to more readily shape the rules and norms that govern the economic affairs of the region.

The BRI may also win China political gains. Beijing may be able to exploit its financial largesse to influence partner country policies to align with its own interests, particularly in certain countries in Central and South Asia that lack good governance and robust rule of law. Some countries that are part of BRI rank unfavorably on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, an index running from 0, indicating very high corruption, to 100, indicating very low corruption. BRI recipient countries with particularly poor Corruption Perceptions Index scores include Turkmenistan (20), Pakistan (33), and Sri Lanka (38).

Accepting Chinese capital may come with expectations that Chinese companies will then be contracted to manage infrastructure, giving them at the least some influence over critical infrastructure. From China’s perspective, investment into strategic locations like Gwadar will help diversify China’s transport network for critical natural resources like oil and gas, which could help reduce dependency on trade routes, such as the Strait of Malacca, through which China currently receives much of its oil and gas.

Partner countries should likewise reap concrete benefits. Fulfilling the infrastructure needs of these countries will speed development by helping them export their products to overseas markets, which could help create new jobs and foster stable growth. Other potential sources of infrastructure finance, such as the World Bank, tie lending to conditions that recipient governments may feel encroach on their sovereignty, such as stipulations that governments limit spending to a certain level or enact anti-corruption measures. Chinese investment on the other hand has been historically less likely to require recipient countries to adhere to such conditions.

Long-term feasibility of the Belt and Road Initiative

China will need to overcome several hurdles for the BRI to succeed. There is a real possibility that offers of investment will be met with lukewarm responses from partner countries that may distrust Chinese motives. This has been evident in past cases of overseas investment by Chinese SOEs not tied to the BRI. Australia, for example, has proven reluctant to allow certain investments by Chinese state companies, and has thus far rejected calls to formally align its state infrastructure fund with the BRI. In 2016, Canberra blocked two investment bids by Chinese SOEs in the energy and agriculture sectors citing national interest and security concerns.

Regional Breakdown of BRI Partner Countries

RegionNumber of CountriesAsia 43

Africa 40

Europe 26

Americas 19

Oceania 10Source: Various

Myanmar has also demonstrated some hesitation in accepting Chinese investment, reversing course from its prior enthusiasm. In 2011 the government of Myanmar halted construction of the Myitsone dam – one of China’s largest investment projects in the country – due to concerns over growing Chinese influence and potential environmental damage. While the project remains in limbo, China was still the largest investor in Myanmar, with more than $15 billion invested in business projects in the country in 2018.

India has expressed significant hesitation toward the BRI. Leaders in New Delhi opted out of both the 2017 and 2019 Belt and Road Forums. In addition to being generally skeptical of the BRI, one specific major concern is the building of CPEC infrastructure through disputed Kashmir.

Interested in learning more about new connections in Asia? Reconnecting Asia is mapping new linkages – roads, railways, and other infrastructure – that are reshaping economic and geopolitical realities across the continent.

Economic considerations further complicate these concerns. BRI infrastructure projects in Central Asia, Pakistan, and Myanmar are projected to lose money due to underutilization and could potentially cause more harm than good. For instance, the Kara-Balta oil refinery – Kyrgyzstan’s largest Chinese investment – has faced significant problems with overcapacity in recent years. Elsewhere, in Thailand, officials are still grappling with the difficulties of financing and negotiating the $9.9 billion Thai-Chinese high-speed railway project in Thailand, which is already long delayed.

Many BRI projects are expected to reap benefits only over the long term, but will tie up large amounts of capital in the meantime that could otherwise be more productively employed elsewhere. This has proven the case with Qinzhou port in southern China, which was slated to function as a crucial hub for trade with Southeast Asia but is still severely underused even five years after completion.

Notwithstanding these hurdles, it is important to recognize that BRI is a long-term plan. Many of its projects are still in their planning phases and will not be completed for years to come. While offers of Chinese investment have been met with mixed responses, should China successfully complete a few keystone projects the reception could become much warmer. This makes the success of the first wave of projects all the more crucial. While it may be many years before the success of the BRI can be properly judged, it certainly has the potential to forge stronger economic and political bonds throughout the region. This deeper integration may grant China more influence over other countries and a stronger hand in guiding development of the international economic system.

No comments:

Post a Comment