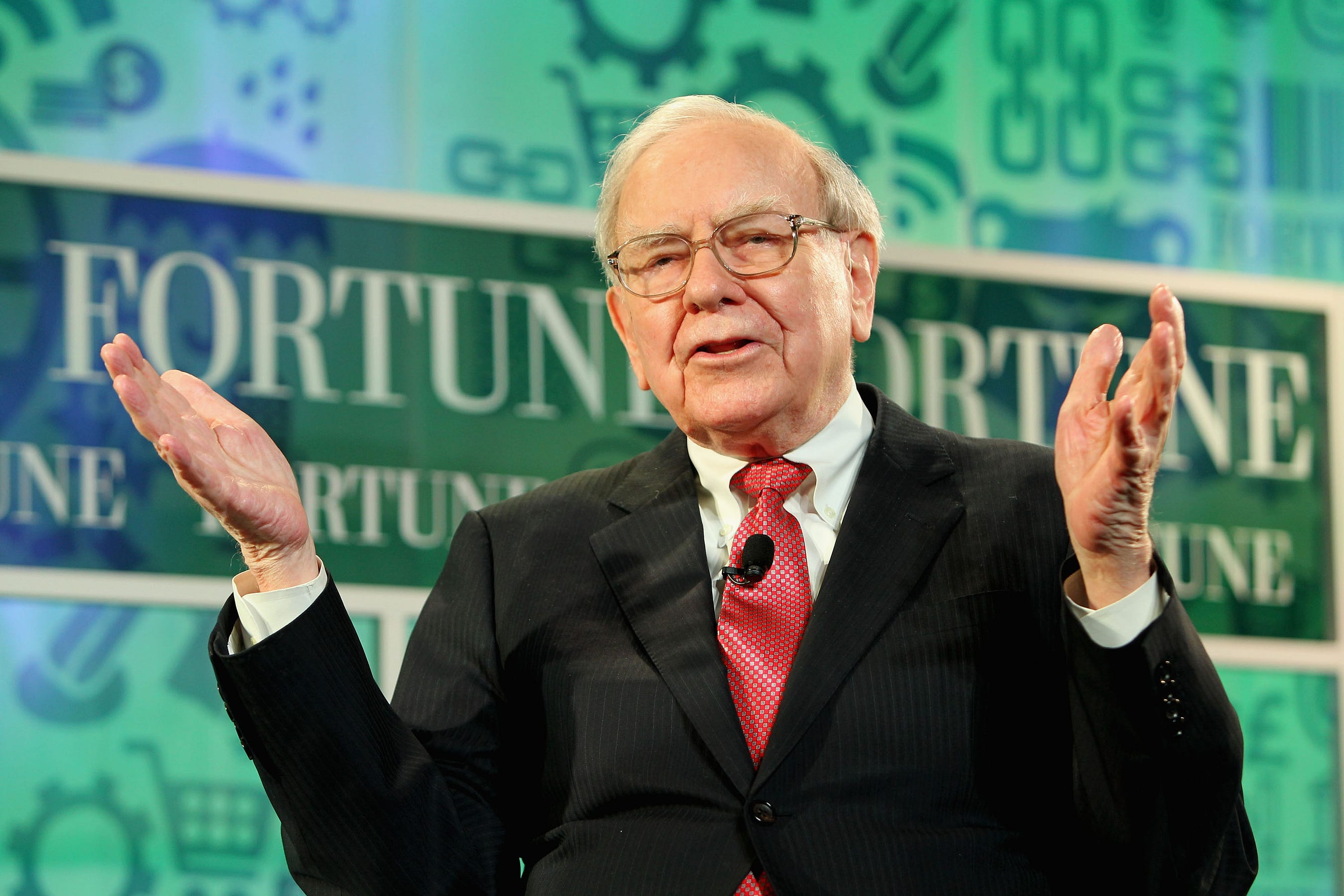

Growing up, I admired nobody more than Warren Buffett, the greatest investor ever. His achievement is towering. The market is an implacable opponent but here was a man who beat it year after year, making $75bn out of nothing but wisdom and charm. There was moral purity in his modesty, his ethics and his quiet attachment to home in Omaha, Nebraska. What footballer, politician or thinker could compare?

Now 87, Mr Buffett wields huge influence over US business and finance, usually positive. He pushed companies to expense stock options, warned of danger in derivatives and taught the public to invest long term in low-cost index funds.

But however much you admire the man, his influence has a dark side because the beating heart of Buffettism, celebrated in a thousand investment books, is to avoid competition and minimise capital investment in the real economy.

A torrent of recent studies show how exactly those forces — diminished competition, rising profits and lower investment — afflict the US. Economists Jan de Loecker and Jan Eeckhout chart a rise in corporate mark-ups, a measure linked to profit margins, from 18 per cent in 1980 to 67 per cent today. In a paper presented at the Brookings Institution last week, Germán Gutiérrez and Thomas Philippon show how investment has fallen relative to profitability. Mr Buffett did not cause these trends. However, they are central to his fortune. When you celebrate him, you celebrate them.

Mr Buffett is completely honest about his desire to reduce competition. He just calls it by a folksy name — “widening the moat”. “I don’t want a business that’s easy for competitors. I want a business with a moat around it with a very valuable castle in the middle,” he said in 2007.

He tells Berkshire Hathaway managers to widen their moat every year. The Buffett definition of good management is therefore clear. If you have effective competitors, you are doing it wrong.

As with many aspects of his career, Mr Buffett used to act more visibly. An example is his 1977 purchase of the Buffalo Evening News. He bought this newspaper for $32.5m, a high multiple of its $1.7m operating profit, then launched a Sunday edition and drove the competing Buffalo Courier-Express out of business. By 1986, the renamed Buffalo News was a local monopoly making $35m in pre-tax profit. At the time, it was Mr Buffett’s largest single investment.

His concept of a moat is linked to his views on capital investment: the beauty of one is you do not need the other. One of his most celebrated purchases is See’s Candies, a company he bought for $25m in 1972. Every year, Mr Buffett raised prices. So strong was its brand that despite sales growing little, profits grew mightily, with barely any need for capital investment. “The ideal business is one that takes no capital, and yet grows,” he said last year.

His statement is unquestionably true for an investor. For an economy, it produces the pattern above: low investment relative to higher profits. A line attributed to business partner Charlie Munger in Alice Schroeder’s biography of Mr Buffett, The Snowball , is revealing: “Munger had always kidded Buffett that his management technique was to take out all the cash from a company and raise prices.” That does sum it up.

If Mr Buffett in his brilliance had found a few truly unusual companies and bought them on the cheap there would be no issue. But acolytes are taking his methods economy-wide.

These days, Mr Buffett has two main ways of putting his money to work. On one hand, he is finally investing in physical assets, although only in regulated industries such as electricity and railroads where returns are largely guaranteed. On the other, he is working with Brazilian private equity firm 3G as it slashes costs to the bone and drives up margins at Burger King and food company Kraft Heinz.

Kraft now makes a 23 per cent operating margin and an enormous return on tangible capital. In a competitive market, those high margins ought to present an opportunity for rivals to invest and steal market share. Instead, Kraft competitors such as Unilever and Nestlé are under pressure from their owners — a mixture of index funds and Buffett-like activists — to match those sky-high margins. If rivals also cut, rather than invest and compete, Kraft can cut even more. A kind of Buffett equilibrium is taking hold.

To be clear, this is not the only reason for declining investment and higher profits in the US. Nor is there a simple solution. Better antitrust enforcement would help, but recent proposals for a complete revamp of competition policy are not well founded. Although research linking lack of competition to cross-ownership by institutional funds is interesting, it does not capture the reality of private equity operators such as 3G.

We can decide who to admire. Mr Buffett is brilliant at buying into monopoly profits, but he does not start companies or gamble on new ideas. America is full of entrepreneurs who do. Elon Musk is investing in two wildly risky and competitive sectors: automobiles and space. Even the much-reviled Koch brothers built most of their fortune on investment in the real economy. Celebrate that kind of business. It is the kind America needs.

No comments:

Post a Comment