By ROBERT ZARETSKY

A leader who had promised the best of times had led the nation to the worst of times. Impulsive and ignorant, he disdained the civil servants his predecessors depended upon and had instead surrounded himself with a clique of craven counselors. Given to pronouncing rambling speeches and driven to prove himself on the world stage, he had a weakness for military parades and provocative claims. “The sad and worrisome thing,” concluded one of the ruler’s closest advisers, “is that for him appearance trumps substance.”

A leader who had promised the best of times had led the nation to the worst of times. Impulsive and ignorant, he disdained the civil servants his predecessors depended upon and had instead surrounded himself with a clique of craven counselors. Given to pronouncing rambling speeches and driven to prove himself on the world stage, he had a weakness for military parades and provocative claims. “The sad and worrisome thing,” concluded one of the ruler’s closest advisers, “is that for him appearance trumps substance.”

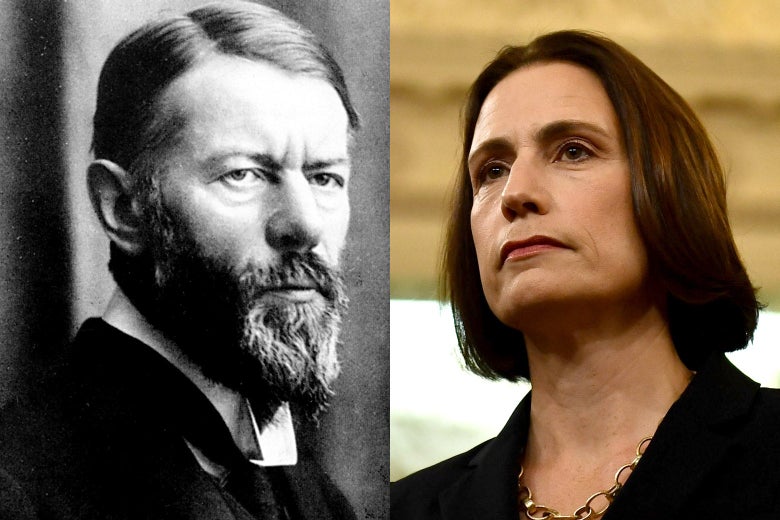

So stood the state of affairs in Wilhelmine Germany in November 1917 when the sociologist Max Weber gave a public lecture at the University of Munich. The talk was published under the title “Science as a Vocation”, along with its companion piece “Politics as a Vocation,” two years later. At first glance, a lecture devoted to science and vocation seems as irrelevant to imperial Germany’s dire political situation as it does to our own a century later. Yet the essay remains one of the most lucid accounts of the relationship between policy and power—or more starkly, between those who propose and those who dispose—and one that casts a powerful light on last week’s House impeachment hearings.

Weber’s lecture was draped in great expectation and drama. By 1917, he was not just an academic but Germany’s most famous and influential public intellectual. Hence, his use of the terms science and vocation carried far beyond the academy. By science, he wasn’t just referring to laboratories, telescopes, mathematicians, and chemists, but to any specialization based on fact and analysis. Wissen, the German word usually translated as science, also means knowledge, and perhaps even the wisdom that issues from knowledge. As for vocation, Weber meant an activity that, in an elusive yet essential sense, transcends mere work. To have a vocation—Beruf in German—is to have a calling. For Weber, who never fully escaped his Calvinist background, the intensity of this calling bordered on the religious.

Famously, or infamously, Weber insisted that science cannot provide ultimate meaning or lasting truths. All it can do, instead, is provide the means in order for us to pursue what we, in all our glorious irrationality, hold to be true or meaningful. Tell me what you want to achieve in a particular field, the specialist declares, and I will tell you what you need to do. But there is a crucial proviso: The scientist, by explaining the method that must be followed, also obliges us to give a coherent account of the meaning of our own actions. By introducing what Weber calls “inconvenient facts,” she invites us to reflect upon the potential consequences of our actions.

Wilhelm’s love of pomp and circumstance and his bluster and bluffs had unsettled other countries and isolated Germany on the world stage.

As a political scientist, and not a political commentator, Weber identified those inconvenient facts that, like the trenches and craters along the western front in the world war that was then ongoing, pocked the government’s foreign policy aims. He methodically dissected the character and consequences of the personal rule of Wilhelm, a ruler whose love of pomp and circumstance and whose bluster and bluffs had unsettled other countries and isolated Germany on the world stage. For a leader who chose his policies with less thought than he did his military uniforms, it is not surprising that he treated his civil servants with less respect than he did his personal servants. The duties of these civil servants were hardly helped by a kaiser who was, in Weber’s words, “an absolutely immeasurable factor”—in short, a ruler who was as unpredictable as he was, in every sense of the word, unthoughtful.

It is, of course, under the shadow of America’s current “absolutely immeasurable factor” that our civil servants, in particular those at the State Department, now labor. It was striking to see how closely the traits of the specialists in the foreign service resemble those that Weber applies to his ideal scientist more than 100 years ago. In his lecture, he summarized them as having “a sense of duty, a commitment to clarity and a feeling of responsibility.” A glance at the “12 Dimensions” listed by the State Department for potential foreign service specialists suggests that Weber’s geist hovered over its authors. Candidates for this department must be able to absorb and retain “complex information drawn from a variety of sources and draw reasoned conclusions from analysis and synthesis of available information.” Moreover, they must be capable of discerning “what is appropriate, practical and realistic in a given situation” and “to weigh the relative merit of competing demands.” Finally, they must be “fair and honest,” “avoid deceit,” and “present issues frankly and fully, without adding subjective bias.”

In her opening statement to the House Intelligence Committee, former National Security Council Russia analyst Fiona Hill distilled these qualities in a few limpid lines. “I am a nonpartisan foreign policy expert,” she stated, “who has served under three different Republican and Democratic presidents. I have no interest in advancing the outcome of your inquiry in any particular direction, except toward the truth.” Hill was insisting upon the factual and often inconvenient truths essential for those who, with our national interest always uppermost in their minds, guide our actions on the world stage.

What the 12 Dimensions leaves out, but was exemplified by Weber and the witnesses, was the imperative of vocation. Ambassador Marie Yovanovitch cited this quality as the defining characteristic of foreign service officers: We are, she announced, “public servants who by vocation and training pursue the policies of the President, regardless of who holds that office or what party they affiliate with.”

As he gazed at the expectant faces of his students, Weber warned that, without this vocation, they might as well find a different occupation. “Nothing has any value for a human being as a human being,” he affirmed, “unless he can pursue it with passion.” But he quickly added that passion does not guarantee success. There is, in fact, a tragic quality to the pursuit of such vocations.

Despite the inconvenient facts he underscored in his merciless analyses of Germany’s war aims and methods, Weber failed to persuade Wilhelm and his spineless court. Similarly, Weber’s inheritors in our State Department have been no more successful with Donald and his equally supine appointees. Germany’s all too foreseeable defeat, and the social and political upheavals that followed, nearly overwhelmed Weber. Yet he continued to work passionately on behalf of Germany until 1920, when he fell victim to the influenza epidemic. As he concluded in his lecture, “We must go about our work and the challenges of the day both in our human relations and our vocation.”

As for the challenges of our own day that confront foreign service officers, as well as all of those who share their “truths,” they could do worse than recall Weber’s description and devotion to their calling.

No comments:

Post a Comment