By SYDNEY J. FREEDBERG JR.

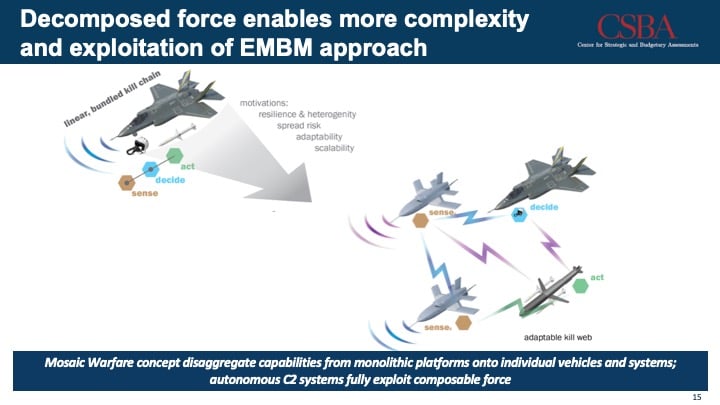

CSBA calls for networks of manned and unmanned systems, each performing a specialized role. (Credit: Center for Strategic & Budgetary Assessments)

Despite rising budgets and high-level attention to electronic warfare, the Pentagon’s “efforts have been unfocused and are likely to fail,” warns a congressionally mandated study out today. What the US needs, the Center for Strategic & Budgetary Assessments report says, is a radically new approach that can outfox Russia and China.

In the much-delayed 2020 budget, the Pentagon requests $10.1 billion (in the unclassified budget) for electronic warfare – but the lion’s share goes to traditional platforms like the Next Generation Jammer for the Navy’s EA-18G Growler and the SEWIP system for surface warships. (The Army and Air Force have largely disbanded their EW corps and left the mission to the Navy since 1991, and they’re only now trying to rebuild). These platforms are big, they’re expensive, they have humans aboard, so they’re not expendable – yet their radars, radios, and jammers give away their presence to the enemy by emitting powerful signals.

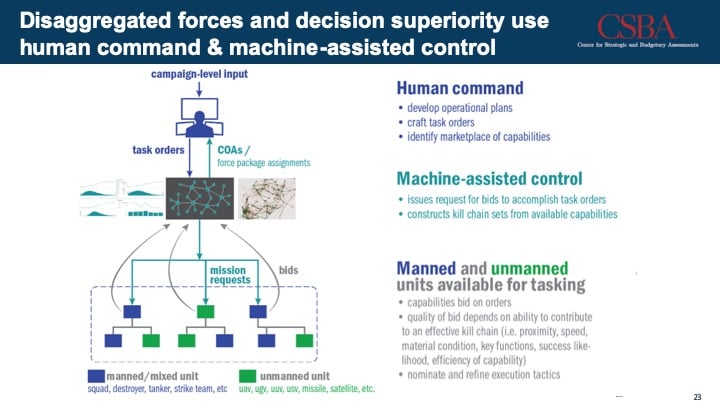

CSBA proposes Uber-like algorithms for matching missions to units (Credit: Center for Strategic & Budgetary Assessments)

On top of that, China and Russia have invested heavily in traditional platforms – planes, ships, and heavy trucks laden with high-power antennas – and the US just can’t match them on their own terms, CSBA warns. Instead, the US should leapfrog ahead of its adversaries by deploying a new generation of both technology and tactics. Imagine a network of manned and unmanned systems, with relatively expendable drones actively emitting signals while the rest of the force stays silent, stealthy, and survivable. Imagine a multi-domain command and control network that can pull together forces from air, land, sea, space, and cyberspace, reorganizing as needed on the fly. The goal: create a dispersed, flexible force our authoritarian adversaries’ centralized systems can’t keep up with.

How would that work? “It is essentially like Uber,” lead author Bryan Clark told me. “A commander inputs the task he or she wants the force to do, identifies the units to be made available for tasking, enters some constraints like geographic bounds, timing, etc., and the system comes back with some proposed courses of action. To develop the courses of action, the system runs an auction across all the units available to determine which can best accomplish the tasking” – much the way Uber’s algorithm match passenger’s desired pickup points and destinations with available drivers, in seconds, millions of times a day.

Of course, the artificial intelligence driving this kind of Joint All-Domain Command & Control system would have to be much more sophisticated than Uber’s. Instead of just distinguishing between regular rides, group rides, and luxury cars, it would need to know the capabilities of different types of drones, planes, ships, ground vehicles, satellites, and more, then calculate which was best able to do a mission based on both its inherent capabilities and its current location. Instead of just knowing where to drop off a passenger, it would need to figure out the best kind of bomb to drop, or jamming to conduct, or malware to deploy, against a wide variety of targets.

Part of CSBA’s inspiration is the DARPA concept called Mosaic Warfare, Clark told me. In very simplified terms, DARPA argues a traditional military organization is like a jigsaw puzzle, where every piece can fit in one and only one place in the larger picture; the future organization needs to be like a mosaic, where a set of tiny building blocks can be combined in all sorts of ways to make an infinite variety of images.

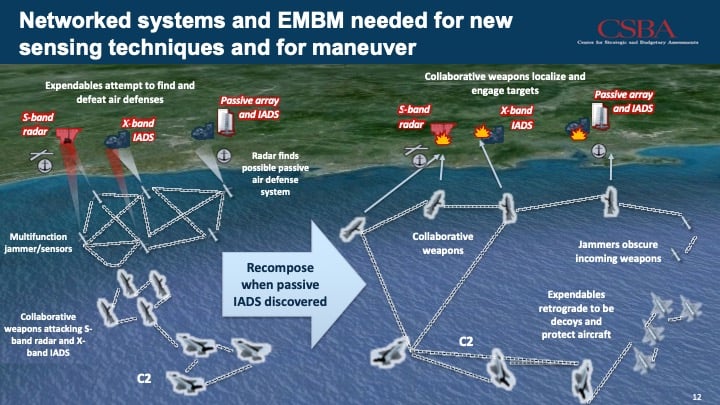

Much like the Internet, this kind of networked force could survive enemy attack – physical destruction, hacking, or jamming – by reorganizing itself to pass data around the damaged nodes, Clark & co. argue. That would make it much harder for Russian and Chinese forces to cripple it by jamming a few key links or physically destroying major headquarters, bases, ships, and satellites.

CSBA scheme for electronic warfare and Electromagnetic Battle Management (EMBM) on land, sea, and air. (Credit: Center for Strategic & Budgetary Assessments)

Israeli defense sources say they believe the types of targets and the Iranian casualties incurred will force Iran to retaliate. At least 23 were killed in the night attacks across Syria, 16 of whom are believed to be Iranians.

“The growth in DoD EW spending…. is not guided by a coherent vision of how U.S. forces would operate and fight in the EMS and is unlikely to yield significant improvements against China and Russia,” CSBA says. That’s in large part because “it is concentrated in a few platform-centric EW programs such as the ALQ-249 Next Generation Jammer [which goes on Navy EA-18G Grower jets] and SLQ-32 Shipboard EW Improvement Program [aka SEWIP, which goes on surface warships]. These systems update existing programs, but do not fundamentally change the way US forces operate.”

And a fundamental change is what’s required, CSBA argues. In stark contrast to Russia and China, the US military puts a high value on initiative and improvisation by junior leaders – but it doesn’t actually give those leaders the sophisticated planning tools to understand a complex, changing battlespace and execute a sophisticated response.

“The tools available to field commanders are insufficient to enable them to develop and plan creative operations. As a result, commanders, particularly junior ones who lack large planning staffs, will tend to fall back on doctrine, habits, and traditions that the enemy can predict,” CSBA argues. “The essential element of this new C3 [Command, Control, & Communications] approach is the development of new planning tools” – like some DARPA has been working on – “that enable leaders up and down the chain of command to creatively plan, adapt, and recompose their forces and operations.”

These new tools would help commanders rapidly retask and reorganize a new kind of force. Instead of relying on large, powerful aircraft that can do all aspects of an electronic warfare mission alone by themselves – which simplifies both US planning and the enemy’s countermeasures – the future force would disaggregate capabilities across multiple manned and unmanned platforms. Expendable drones might emit radar signals, while other drones and manned systems would passively receive the radar returns, then compare notes over hard-to-detect datalinks to figure out where the enemy forces were. Other expendable drones – possibly launched from a manned mothership — could transmit the powerful signals required for jamming, but every unit in the network would have the capacity to passively listen for enemy transmissions.

Now, CSBA doesn’t call for canning the Pentagon’s big ticket programs – just trimming them to free up funds for more smaller and more innovative items. “Replacing a small portion of today’s multi-mission ships, aircraft, or troop formations with smaller, cheaper and less multifunctional units would be enough to enable significantly more adaptability in US forces packages while imposing considerable complexity on adversaries,” the report argues.

China in particular – which has much greater resources than Russia, but much less actual combat experience – relies heavily on detailed advance planning and centralized control, CSBA says. “The relatively static and inflexible nature of PLA military systems and [its] continued reliance on centralized, consensual decision-making may create opportunities that US forces could exploit,” the report argues – if the US can build military technology and organizations that truly empower its people.

No comments:

Post a Comment