Brad W. Setser

No modern president believed as strongly that reducing the trade deficit could deliver a sustained boom to the United States economy (and particularly those parts that had been hard hit by the 2015-16 industrial recession).

And Trump can hardly be accused of inaction—he has engineered a revolution in U.S. trade, putting substantial tariffs on around two-thirds of U.S. imports from China (the largest single supplier of goods to the United States), rewriting NAFTA, and threatening broad action against auto imports.

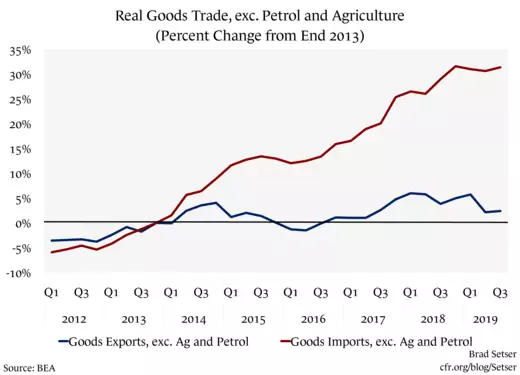

Yet, well, the gap in non-petrol goods trade keeps on rising. The chart data is in real or volume terms. I also took out agriculture as it has its own sources of seasonal volatility but adding it in wouldn't change the trend.*

Share

The intensification of the trade war has slowed real import growth in the past few quarters—imports from China are down, and imports from the rest of the world are up, but not up by enough to fully keep import growth on trend. Of course, that slump in imports also came at a cost to the U.S. economy (tariff revenues are a form of fiscal tightening, plus uncertainty around trade policy has likely dampened investment in some sectors).

But the trade deficit isn't shrinking, because exports are down too—the gap between import and export growth that opened up after the dollar appreciated back in 2014 hasn’t gone away.

It is almost as if trade policy decisions—unless they are truly radical, with across the board tariffs that deliver a large fiscal tightening—impact the level of trade more than the balance of trade.

That after all is what most macroeconomists predicted. Tariffs would impact individual sectors, but not the broad pattern of trade—which is set by variables like the dollar, the relative pace of U.S. demand growth and demand growth in U.S. trade partners, and perhaps China’s ongoing “deglobalization” (China’s import growth has consistently lagged its GDP growth over the last 8 years; 2017 is the exception not the rule).

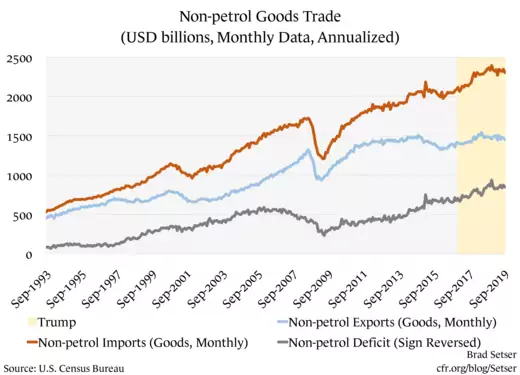

Trump’s approach, judged on his own terms, hasn’t really worked. The non-petrol trade deficit is up over the course of his term.** No wonder Trump wants Jay Powell to bring interest rates and the dollar down.

Share

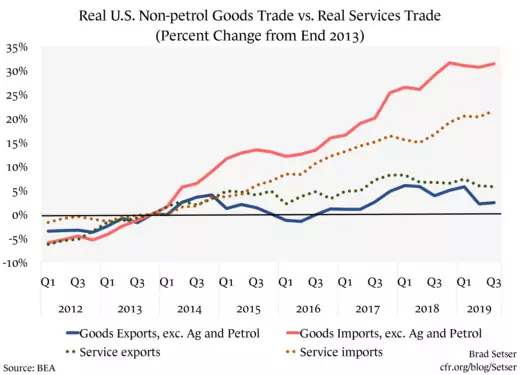

The post-2014 slowdown in export growth, incidentally, is as apparent in the services data as in the goods data. Tourism trade in particular does respond to changes in the dollar.

Share

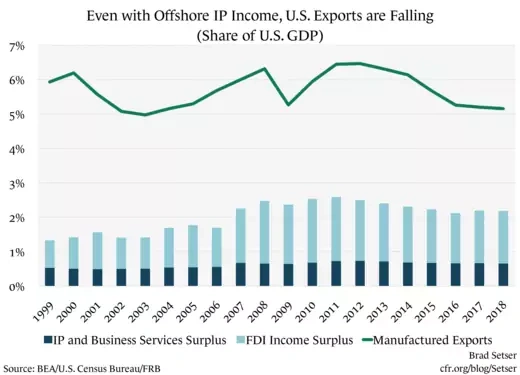

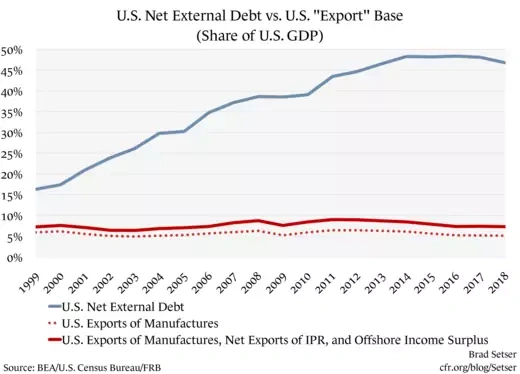

As a result, over the last five years the fall in manufacturing exports as a share of GDP hasn't been offset by higher service exports, or even higher offshore profits of U.S. firms. The U.S. has slowly been deglobalizing on the export side—

Share

Oil has provided an important offset. The United States no longer imports more oil than it exports. But the U.S. isn't likely to be a major oil exporter either—U.S. consumption is too high.

Consequently, the ongoing slide in other exports relative to U.S. GDP isn't really sustainable in the long-term. Of course, the long-run can be very long—nothing precludes a rise in the United States external debt (as a share of the economy) above its current levels even as exports shrink (relative to the economy, and relative to imports). Lower long-term interest rates in theory allow more external leverage. But make no mistake, U.S. external debt has already risen substantially relative to the United States' export base over the last twenty years.

Share

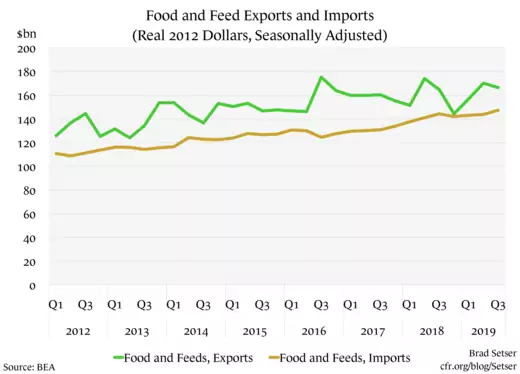

* Real agricultural exports were hit by China’s retaliation in q4, but are currently running at about their normal pace. Here the seasonal adjustment likely deceives—China didn’t buy when it should (pulling down q4) but it has been buying a bit when it shouldn’t (q2 and q3) and out of season exports can have a disproportionate impact thanks to the seasonal adjustment. Nonetheless, for now, the “real” shock to agricultural export volumes looks modest. That isn’t to say farmers aren’t facing tough times—though their difficulties stem at least as much from the dollar’s 14-15 appreciation and the commensurate fall in dollar prices for key agricultural commodities as to the trade war.

Share

** The nominal non-petrol goods deficit has increased by about $400 billion over the last five years, about half of that increase followed the dollar's 2014-15 appreciation, and the other half followed Trump's stimulus.

Share

No comments:

Post a Comment