George Friedman

The Chinese People’s Liberation Army has begun minor operations to try to quell the unrest in Hong Kong. This is a step that the Chinese hoped to avoid. For one thing, they wanted to portray the unrest as minor, not requiring their intervention. For another, they did not want issues raised about Chinese human rights violations, which inevitably emerge in such interventions. At a time when China is trying to portray itself as the global alternative to the United States, it doesn’t want other countries, particularly those in Europe, noticing human rights abuses.

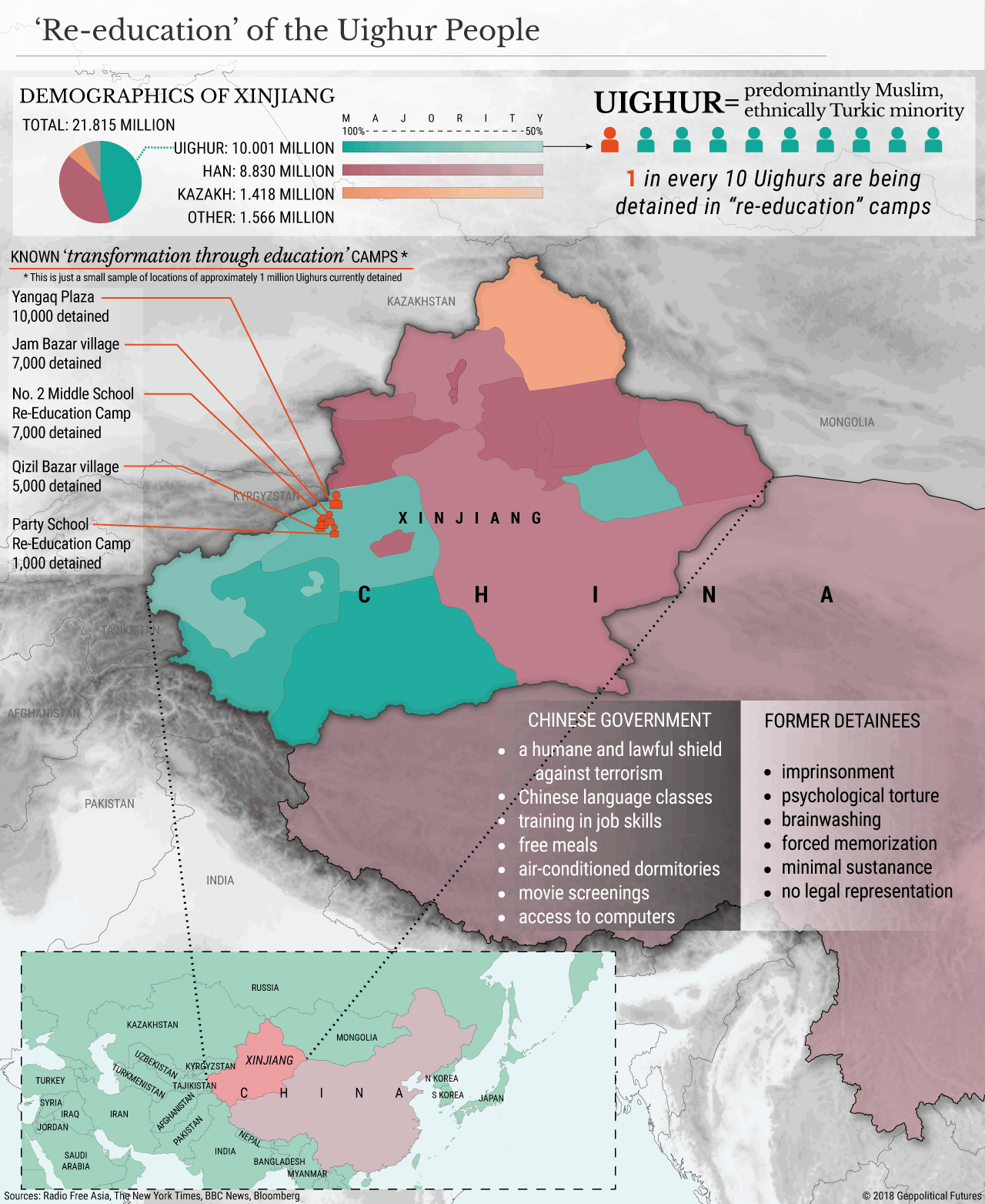

This strategy took another huge blow with the leak over the weekend of government documents describing in detail a broad Chinese assault that has been underway for several years on the ethnic minority Uighur community in the western province of Xinjiang. The documents gave detailed accounts of massive detention camps for “retraining” purposes and the separation of families on a scale that is startling even for China. Beijing clearly wants to break the back of Islam in the province.

Chinese detention of Uighurs is not new. We have been hearing about this for over a year. What is startling is the leak of documents so sensitive that they validate claims of mistreatment that the Chinese long denied, for obvious reasons. This raises a key question: Who released the documents? They might have been leaked by Chinese officials, appalled at what is going on in Xinjiang. They might have been released by the Chinese government as a warning to other dissident groups. They may have been released by senior members of the Chinese government who have become disillusioned by President Xi Jinping, hoping to force him out.

All three are possible, but to understand the events in Xinjiang, we need to also consider what’s happening in Hong Kong. The Xinjiang detentions predate protests in Hong Kong by quite a while but demonstrated a turn of the Chinese government away from liberalization. Xi had already taken that turn during his massive anti-corruption purge, which obviously was a cover for a systematic purge of real and potential opponents. The demonstrators in Hong Kong watched the purges and the events in Xinjiang, and realized that the fairly radical extradition bill, which sparked the initial protests, was the cutting edge of an attempt to force Hong Kong to submit to the Chinese framework and to Beijing’s power.

That is what is happening in Xinjiang, a province that is formally part of China but not Han Chinese, the majority ethnic group in China. Han China is surrounded by four buffer states: Manchuria, Inner Mongolia, Tibet and Xinjiang. Its eastern coast is dotted by former European enclaves, such as Hong Kong and Macao. Over the years, the Chinese struggled to retain these buffers. Japan seized much of Manchuria in World War II, with less than unanimous opposition. There have been uprisings and resistance in Tibet. Xinjiang was rumbling with Islamist sentiment. And while Macao accepted mildly the redefinition of its status, Hong Kong exploded at what it saw as an attempt to redefine its status prior to negotiated dates.

Tibet’s resistance, led by the Dalai Lama, remains. Manchuria and Inner Mongolia are pacified. But Hong Kong and Xinjiang are the real dangers. They cannot be left to fester, lest Islamist terrorism spread to Chinse cities, or Hong Kong serve as an inspiration to other cities in eastern China. The efforts needed to pacify them, however, carry costs outside of China. The Belt and Road Initiative could turn from being an ambitious Chinese project into a symbol of Chinese repression. This is not an image China wants to project.

For months, riots on the streets of Hong Kong have been broadcast on global television and discussed over social media. Those who have been paying attention have known about the repression of Uighurs in Xinjiang for a while, but it had not entered the global zeitgeist. Until now. Xi, who came into office as the central power that would modernize China and make it a great power, is now facing three domestic problems. The first is the fading memory of the anti-corruption purges. The second was the festering repression in Xinjiang now made virally public. The third is the riots in Hong Kong. In the first two cases, China is made to seem Stalinist and fascist. In the last case, it appears inept, unable to bring the matter to a close. To put it another way, the Chinese clearly wanted Hong Kong to settle down without action from Beijing to drive home the message that China is modernizing despite the Xinjiang affair and the purges. But Hong Kong may not fade away and the PLA might have to enter Hong Kong in force.

China needed to present itself to the world as a burgeoning economic power and a benign political power, overseeing a united mass of people moving forward in history. The purges raised eyebrows but could be dismissed as what they were claimed to be: an anti-corruption campaign. Xinjiang was far away and, for most people, out of focus. But Hong Kong is not far away or out of focus. It forces us to see the other two issues in a different light. Now we see China not as a symbol of progress, but as a fearful nation struggling to repress discordant elements.

This brings us back to the question of who leaked the documents. There are three possible explanations for the leak. First, Xi’s team might have leaked them to show his determination. Second, they might have been leaked by someone in the government who was appalled by what they saw. Finally, they could have been leaked by an emerging anti-Xi faction in the Central Committee, appalled by Xi’s handling of the United States and Hong Kong and using the documents to weaken him. Of the three, I favor the third explanation. Too many important things are going wrong in China for such a faction, however small at this point, not be forming.

Xi’s incompetence is manifest. The major task of the Chinese president is to handle the American president, and Barack Obama, George W. Bush and Bill Clinton were handled. He failed to bring Donald Trump under control with promises of future meetings and postponed studies. As a result, China is in a trade war with its largest customer. In addition, quite apart from the trade issue, the Chinese financial system is unstable and growth is slowing. Now, Hong Kong is out of control, and the global talk is of Chinese concentration camps. This is not what was expected from Xi.

The Central Committee is the ultimate arbiter of what China does, particularly if the president weakens and loses his way. There must be some in the Central Committee who remember Xi’s inauguration and have concluded that China’s evolution has not gone the way they expected and Xi promised. The Central Committee is usually opaque, as it is now, but if there is opposition developing to Xi, and it is hard to imagine there is not, then release of these documents merely turns a known event into a global event, further showing Xi’s incompetence.

All of this is framed by a primordial fear. Before Mao’s victory, regional conflicts tore China apart and allowed the Japanese to seize major parts of the country. Regional conflicts in the future are the single biggest threat that China does not want to face again. The Chinese are suppressing the threat in Xinjiang, and now maybe in Hong Kong. But China does not want to have to suppress regional threats. Xi, however, is doing just that and he also came in suppressing political threats with the purges. Between that and mishandling the Americans, many nerves are being touched. I would bet that the leak came from the Central Committee, and that Xi has enemies.

No comments:

Post a Comment