By Jacek Bartosiak

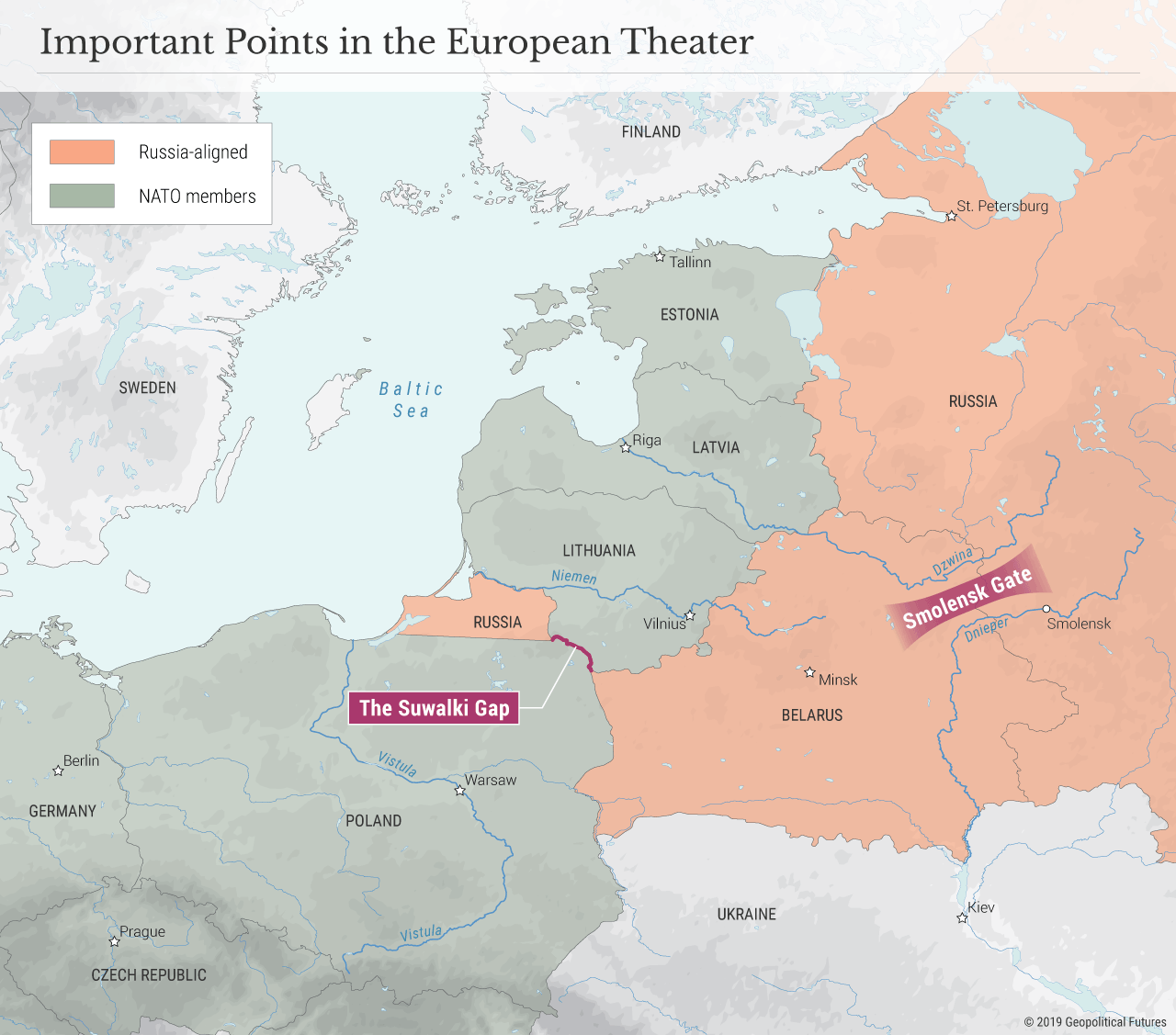

The frequently cited Suwalki Gap is the only communication route connecting Poland – the operational base of NATO and the U.S. – to the Baltic states, which abut Russia and thus are vulnerable to Moscow’s military advances. This narrow area is essential to sustaining NATO cohesion and guaranteeing the collective security afforded by NATO. In military terms, NATO’s Line of Communication, or LOC, through the gap is extremely difficult to establish and maintain; it traverses a challenging terrain over a long distance, from Warsaw to Tallinn, and since it is flanked by Belarus and Kaliningrad, it is vulnerable to Russian anti-access/area denial assets. (Indeed, the importance of Belarus and Kaliningrad cannot be overstated. They affect NATO’s general strategy, the escalation ladder, nuclear aspects, political dimension, cohesion of the alliance, and so on.)

However, the Suwalki Gap is less important to Poland – whose independence would remain intact even if Russia invaded the Baltics – than it is to Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia. And it is far less important than the Smolensk Gate – more on that in a moment. The Baltic states are like three pieces of meat on a skewer comprising a single road route from Poland that passes through terrain less than 90 kilometers (60 miles) wide at its narrowest point. The fact that a single LOC can be cut by a potentially hostile Russian force, therefore, demands an analysis of what it would take to discourage Russian aggression.

The Smolensk Gate

The Smolensk Gate is situated between the Dnieper and Dzwina river systems in an area that has historically been the primary avenue of invasion from Russia to Poland. The terrain itself channels the movement of military forces, rendering it the most strategic area in Central and Eastern Europe and making Belarus a key element of the geostrategic architecture of Central and Eastern Europe.

For Poland, the Smolensk Gate makes the Baltic states a secondary area of operation in any major confrontation with Russia. Poland is most vulnerable on this axis, as is Russia. Essentially, Belarus serves as the potential battlefield. NATO security policy in Eastern Europe must take this reality into account since it decouples the interests of Poland from the U.S. and the Baltic states. Russian military theorists understand as much, hence the 2016 formation of the powerful 1st Guards Army at the entrance to the Smolensk Gate. This single Russian army has more offensive weapons than all of the Baltic states, Poland, Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg combined. The covering force on this axis consists of one skeleton Polish brigade and one Polish cavalry regiment. Behind the 1st Guards Tank Army is the 20th Guards Army, which is currently being organized and which will have equally substantial firepower.

Eastern Europe is less a conventional flank than it is a strategic region with three fronts: the Baltics, Belarus and Ukraine, with Poland, to borrow a term from Carl von Clausewitz, serving as its center of gravity. NATO force deployment will determine the course of any war and thus the fate of the Baltic states, Poland and Belarus. While NATO military planners are focused on the operational-tactical issues, the alliance needs to also conceptualize the geostrategic aspects of Russian coalitional warfare plans.

To be sure, those plans exist. Since 1999, three Russian Zapad military exercises have simulated invasions of the Baltic states and Poland. Russia’s 6th Army, too, has frequently practiced invading them. Moscow has recently reinforced the 6th Army with additional self-propelled multiple rocket-launcher systems and practiced massive notional fire-strikes against the Baltic states. As part of its force package against the Baltic states, the Russians have added artillery to the 76th Air Assault Division at Pskov.

Russia’s Point of View

From Russia’s point of view, Europe comprises three strategic directions: northwestern, western and southwestern. The western and southwestern directions in this European theater of operations include three fronts: the Baltic, the Belarusian and the Ukrainian. Within this area, the Dzwina, Dnieper, Niemen, Bug, Vistula and Narew rivers create a complex, intersected battlefield with the massive swampy terrain of the Polesia dividing the Belarusian and Ukrainian fronts.

Contrary to the conventional wisdom that the Baltic front lacks sufficient depth to be successfully defended, the region is approximately 300 kilometers deep and features rivers, streams, swamps and densely forested terrain that impedes maneuver warfare. The terrain provides ample opportunity to conduct defensive operations to halt rapid movement and to attrite attacking forces.

The Belarusian front, which ends at the Smolensk Gate, is located north of the Polesia and south and east of the Dzwina and Niemen rivers and features reasonably accessible terrain for at least part of the year. Forces may, at times, move reasonably rapidly. Except for the upper Niemen and Shchara rivers and their respective swampy valleys, there are no prohibitive terrain barriers preventing movement. This has always been the shortest and most convenient approach from Russia to Poland, with staging areas near Minsk, Orsha and Vitebsk, backed by the strategic depth of Russia proper and its vast resources.

Any Russian approach along the Belarusian front will cut off the Baltic states, deny them access to their ports and may rapidly bring war to central Poland near the northwestward curve of the Vistula River, i.e. to the very heart of Poland. The geography of central Poland lures potential attackers into an area north of Warsaw that cuts the Gdansk operational line and denies any cross-Vistula reinforcement form western Poland. Yet, that gives the defender sensible options for counteraction from the south (but east of the Vistula River) to cut the operational line of the attacking forces, provided that the attacking forces on the Ukrainian front do not threaten to flank any such counteroffensive.

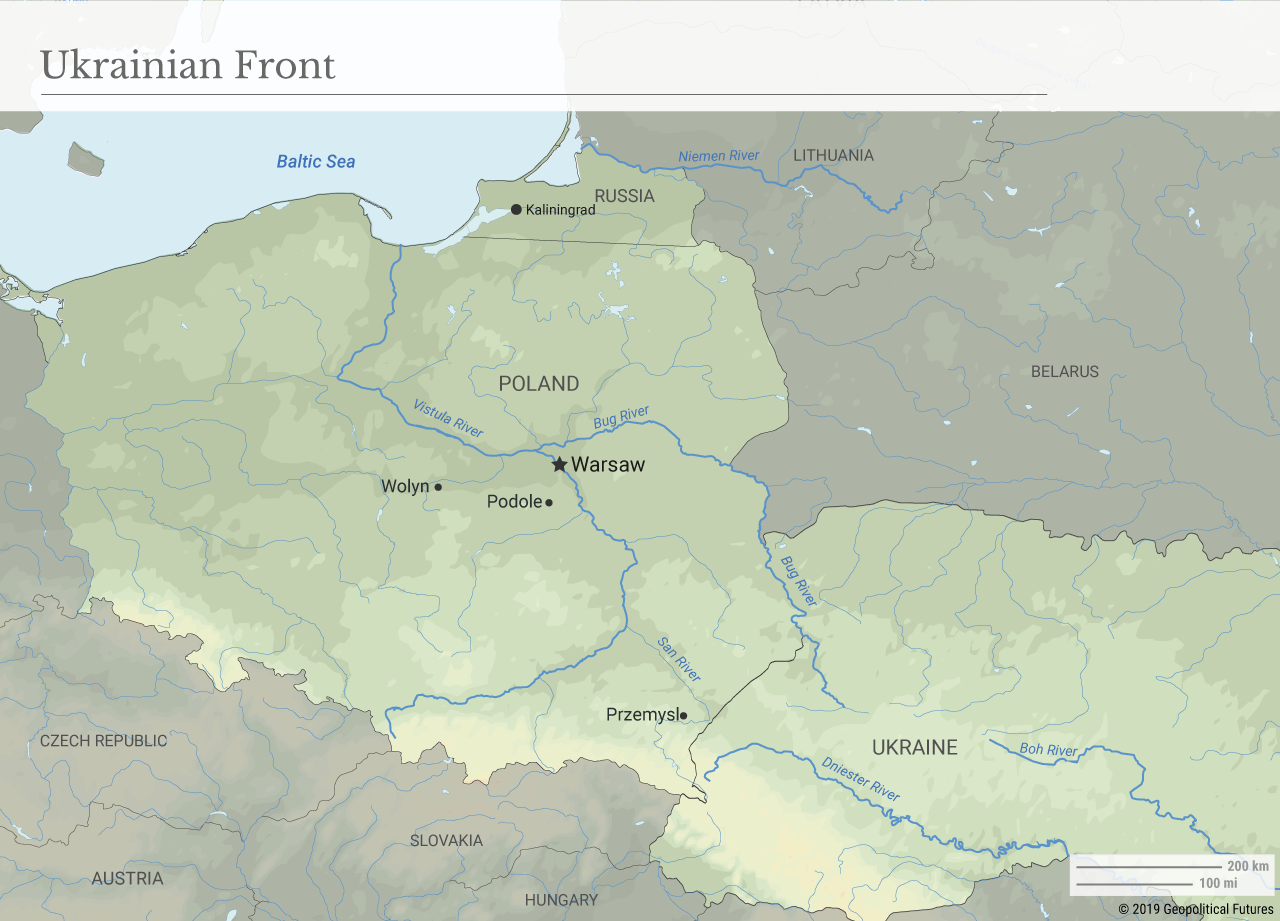

The Ukrainian front of Podole, Wolyn and Ukraine proper has no substantial barriers and is perfect for mass tank warfare, except for the massive Dnieper River. East of the Zbruch River, the steppe rolls along the Dniester River with no forests or obstacles making tank use even easier.

The approaching forces may enter Poland through the permissive terrain of Przemysl Gate, which allows for a concentration of attacking forces. This region used to be perfect for massive cavalry deployments and maneuver warfare dating back to ancient times along the famous route of the big steppe nomads conquering Europe from Asia.

The last line of defense before the Vistula River and Warsaw is the Niemen and Bug rivers, which connect south with the Boh and Dniester rivers in what is now Ukraine. The area is cut horizontally by the Polesia swamps, creating two separate fronts, one of which has historically been neglected to the benefit of the other. Napoleon neglected the Ukrainian front in the south in 1812, when he could have sealed his victory by separating grain-rich Ukraine from the Russian Empire. After seizing the Smolensk Gate, Hitler failed to exploit the prospect to close in on Moscow and instead decided to turn south to the Ukrainian front losing precious time and – as a consequence – losing the war. In 1920, the Soviets failed to advance fast enough on the Ukrainian front, thus failing to connect with the Belarusian front units. This permitted Polish forces to defeat Soviet armies approaching on the Belarusian front in the battle of Warsaw in August and later in the battle on the Niemen River in September 1920, thereby sealing the victory in the war for Poland.

The new realities recall the contemporary Polish military and planners of the eternal patterns of the battlefield of Central and Eastern Europe, proving that continuity in geopolitics and military strategies imposed by geography is more than just a fashionable phrase.

No comments:

Post a Comment