By SYDNEY J. FREEDBERG JR.

DETROIT: “I get so frustrated,” fighter pilot turned Microsoft exec Mark Valentine said, when “senior program officials and my former colleagues from the Air Force [ask me] ‘Dude, I need to get me some of that AI.’ And I shake my head.

DETROIT: “I get so frustrated,” fighter pilot turned Microsoft exec Mark Valentine said, when “senior program officials and my former colleagues from the Air Force [ask me] ‘Dude, I need to get me some of that AI.’ And I shake my head.

“To do what?” Col. Valentine asked the AUSA conference on autonomy and AI here. “What are you trying to accomplish?”

Then there are the customers who know just enough to be dangerous, added Leonel Garciga, an expert in military intelligence IT on the Army headquarters staff (G-2). He’s gotten requests like, “hey, Leo, I want to move my instance of SharePoint” – a popular collaboration tool – “to a Google cloud platform” – a popular cloud provider. “And I said, really? That sounds like not a great idea,” Garciga recalled.

Army soldiers access the DCSG-A intelligence system during an exercise.

Why? SharePoint is a Microsoft product that comes standard on Microsoft’s cloud service, Azure, Garciga tried to explain. Why would you pay Google to do that integration work all over again?

Why? SharePoint is a Microsoft product that comes standard on Microsoft’s cloud service, Azure, Garciga tried to explain. Why would you pay Google to do that integration work all over again?

“And then,” Garciga said, “I get a blank stare.”

Here’s an analogy: Imagine you want a car with a sunroof. Do you buy a car that has a sunroof, or do you buy a car that doesn’t have one and pay a mechanic to take a blowtorch to it?

You really, really, really don’t want to reinvent any wheels by integrating new software you don’t have to, agreed Matt Carroll, a former Army officer who’s now CEO of startup Immuta. Of course, he noted, the companies selling you that software won’t necessarily warn you. All too often, “they believe they can just hand their product over, it goes into cloud infrastructure, and it’s magic and it works,” he said. In reality, he went on, in one case, “it took us a year-and-a-half… just to install our product. A year and a half!”

Installation and integration aren’t the only hidden costs, Carroll continued. The Defense Department wants cloud computing so it can pool data previously scattered across the bureaucracy, making it easier to analyze; machine learning in particular requires a massive central collection of data to train the algorithms. But running sophisticated analytics – let alone AI – requires much more computing power than just dumping 1s and 0s in a database, and it’s correspondingly costly.

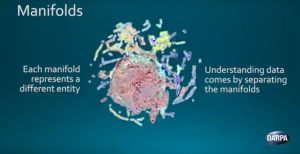

Modern machine learning AI relies on the fact that, in any large set of data, there will emerge clusters of data points that correspond to things in the real world.

“It is very different than a database, very different than cold storage,” Carroll said. “Analytics run in that computer infrastructure, and – guess what? – it’s wicked expensive. It’s like 10 times the cost.

“It is very different than a database, very different than cold storage,” Carroll said. “Analytics run in that computer infrastructure, and – guess what? – it’s wicked expensive. It’s like 10 times the cost.

“People freak out ….‘holy crap, how am I going to pay this bill’?” he said. Well, the whole point of moving your data to the cloud was to make it easier for people to use it, and now they’re using it more. “That’s what you want to do!” he said. “Guess what, there’s a cost for that.”

Such unpleasant surprises in cloud billing were all too common across the defense industry as well, Garciga said – but they’ve learned how to manage it, when the Pentagon has not.

“All major defense contractors that are here, I talk to the folks on the IT side, and I get the same exact story: ‘Leo, we went to cloud…and we had like 3,000 PCs out there, and people were just leaving stuff running, and we had a bazillion dollar bill,’” Garciga said.

The companies responded by instituting new rules for cloud use – much of it the 21st century equivalent of reminding employees to turn the light off before they leave the building – but “that lesson has not been learned by DoD yet,” he said. “That lesson has definitely not been learned by the Army.”

Then-director of the Defense Digital Service, Chris Lynch (at center, in grey hoodie) surrounded by his casually-clad tech geniuses.

“Bureaucracy Hackers”

The Army CIO, Lt. Gen. Bruce Crawford, is now creating an enterprise cloud management office to get a handle on the devilish and expensive details of moving to the cloud. In the intelligence world, which is particularly enthusiastic about cloud computing, “we’ve actually stopped a lot of the technical pieces,” Garciga said, “[while] we’re hiring more business folks to manage the business of cloud vs. technical [aspects]. That’s going to be a bigger challenge.”

Pentagon officials often fixate on hiring people who know computers, but they really need to hire people who know their way around the government’s own bureaucracy, agreed Don Bitner, chief of infrastructure strategy & development for the Joint Artificial Intelligence Center.

“We need to have policy hackers,” Bitner said. “That is a skillset we really need: people that can hack the bureaucracy and get through the red tape, [and] you really only get that skillset through experience.”

(It’s worth noting the Defense Digital Service was created to bring hackers of both technology and bureaucracy to the Pentagon from the private sector, but their most ambitious project, the JEDI cloud computing initiative, has repeatedly run afoul of legal and procedural problems).

The Pentagon’s plan to consolidate many — but not all — of its 500-plus cloud contracts into a single Joint Enterprise Defense Infrastructure (JEDI). Note the suggestion that the single “pathfinder” contract for JEDI might evolve into multiple JEDI contracts.

The Pentagon’s plan to consolidate many — but not all — of its 500-plus cloud contracts into a single Joint Enterprise Defense Infrastructure (JEDI). Note the suggestion that the single “pathfinder” contract for JEDI might evolve into multiple JEDI contracts.

The lack of experience manifests in different ways at different levels of the hierarchy. Naïve generals, admirals, and senior officials all too often try to order up AI – or cloud, or whatever the latest buzz word is – as if it were a side of fries, without thinking through what they really want it to do. But uneducated procurement and contracting officials often see obstacles to high-tech projects, obstacles they could actually bypass if they understood all the options already available to them in acquisition law and regulation.

Special Operations Command, for instance, has a reputation for getting its commandos high tech at high speed and manageable cost, often attributed to SOCOM’s special legal authorities. But in fact, said Bitner, “I might have been doing a SOCOM project, but nine times out of 10 we’d use a standard FAR [Federal Acquisition Regulation] warrant to buy our stuff, and we bought it just faster than the services.

“It’s because we knew how to work the system in our favor,” Bitner said. “You need bureaucrats that are willing to hack the system, not just sit back and tell us [no].”

All too often, Garciga said “we’re delaying operationalizing stuff that I go could build right now in my house, and I could deploy from my laptop, tonight, and we’re turning it into a six-month effort.” And DoD is suffering this “self-inflicted wound,” he said, in large part not because of what the regulations actually say, but because of how acquisition officials have gotten used to coloring well within the lines rather than using all the leeway they really have.

Listening to one litany of obstacles, Garciga said, “at almost every single point, my thought was, ‘oh, well, there’s already policy that allows you to do that.’” It’s just not being used.

Sometimes, officials just aren’t aware of new reforms. About four months ago, Garciga said, the undersecretary for acquisition & sustainment issued new rules for “rapid software provisioning.” He asked anyone who’s heard of the change to raise their hands, then scanned the cavernous conference hall.

“One person. Outstanding,” he snarked. “Everybody should be raising their hand.”

In many other cases, though, the flexibility has been available for years. “How many people think OTA” — Other Transaction Authority, a favorite tool of reformers – “is a new thing?” Garciga asked. “It’s been around forever. We just weren’t using it.

“The policies that are actually in place right now and the law that’s in place allow us to do this,” Garciga said. “Everybody has the authorities to do this. Let’s get that done.”

No comments:

Post a Comment