By Priyansha Singh and Chitra Rawat

In this edition of Gotta Keep on Movin’, we explore the migration trends of minorities in India.Vulnerability manifests along numerous axes — caste, gender, religion.

In this edition of Gotta Keep on Movin’, we explore the migration trends of minorities in India.Vulnerability manifests along numerous axes — caste, gender, religion.

Even as migration increases across the country, minorities increasingly find themselves harassed, indebted and persecuted at their destinations.

Internal Migration and Minority Groups

A study conducted by Chandrasekhar and Mitra (2018) in Jaipur, Ujjain, Ludhiana, and Mathura found that socially better-off classes have a higher propensity to migrate. When the dimensions of caste and migration are combined at the lowest strata of the society, the benefits seem differential. Migration does pay off if the worker is from a higher caste.

Tumbe explains that in the northern states of India, higher castes tend to migrate to towns that are further away from their native village and for longer durations, while the lower castes migrate to nearer towns for shorter durations, say for three months. This discrepancy is explained by the cost of migration.

In Uttar Pradesh historically, mobility was confined to the Brahmins (priestly castes) and Vaishyas (trading castes). But today a large number of labour migrants are members of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. Hindus and Muslims from these communities comprise migrants. Overall, temporary and seasonal mobility is higher among Scheduled Tribes than other caste groups in rural areas.

Inadequate employment opportunities and industrial backwardness, along with the growing price of essential commodities, have made migration an appealing and necessary prospect. Workers can get more opportunities and higher wages in destinations such as Delhi, Maharashtra and Gujarat within India and the Gulf countries, abroad.

As per Census 2001 data, of the total intrastate migrant population, 23.4% migrants were SC and 11% ST. This share further fell and as per Census 2011, only 13.8% and 7% belonged to the SC and ST communities respectively. However data from some states is not available, therefore there is no accurate information available on the exact numbers.

Double vulnerability of female migrants

A survey conducted by the Centre for Women’s Development Studies in 2012 shows that migration among women is increasing but the nature of migration and kind of employment in destination states is not isolated from the caste positions of female migrants. A large number of migrants from the lower castes are medium-term and short-term migrants, unlike their upper caste counterparts.

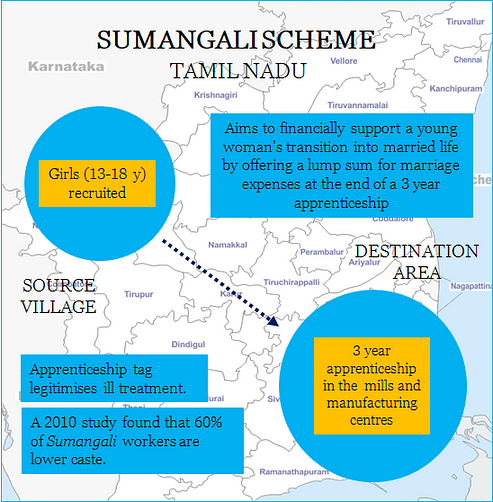

A study conducted in Erode, Coimbatore, Tirupur, Viruthunagar & Dindigul districts of Tamil Nadu in 2010, found that, almost 60% of the Sumangali workers belong to the ‘Scheduled Castes’ or ‘Untouchables’.

If the victim belongs to a comparatively lower caste or a low income group, it becomes an opportunity to pay her a lower wage because her family will not be able to bargain with the employer.

When a woman loses her husband to the sewers of India, besides trying to cope with the loss, she has to fight for justice and worry about her family’s survival.

The story of Rani and Anil from Uttarakhand in Delhi. Last year, Anil who belongs to the Dalit Valmiki community lost his life in a municipal sewer. He had been cleaning sewers for more than 15 years. Read there entire story here.

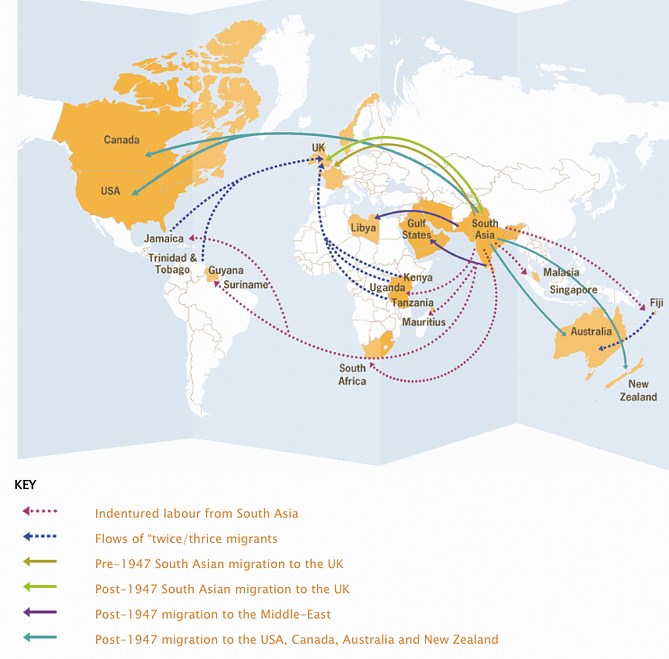

International Migration and Minority Groups

India has the largest international migration stock in the world; about half of it is constituted by women i.e. approximately 8 million. Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and Maharashtra serve as the major sending states of unskilled women workers to the Gulf countries. Kerala leads the path of skilled women migrants; however, their work is largely limited to the nursing industry.

Emigrants face various issues when at the destination, however, the vulnerabilities of male and female migrants differ from one another. Unregistered agents, irregular migration pathways, and some inhumane employers put women who migrate for domestic work in extremely vulnerable positions.

Sister Lissy, who runs a Hyderabad based NGO for the welfare of female emigrants says, “Around a decade back, I saw around 200–300 women surrounding the Hyderabad POE office. I found out that these women had come for Emigration Clearance. I also met some women who had migrated and faced violence. Over the years awareness among women migrants has increased and made them more confident.”

She adds that female migrants, unlike male migrants, are isolated in houses. Even if they are facing violence, they have no one to share it with.Rajan, Tailor and Kumar (2016), in their study, compare Punjab, which has witnessed significant Scheduled Caste (SC) overseas migration, including to Western societies such as the UK, and Kerala, where international Dalit emigration has been insignificant.

The study finds that more migrants from the Dailt community in Punjab were migrating in comparison to Kerala because of greater educational opportunities, occupational diversification and rising incomes, particularly for the Dalits in the Daoba region of Punjab. In fact, of the total emigrants in Kerala only 7.1 per cent and 1.7 per cent were Hindu SCs and STs respectively.

The percentage share of SC and ST among converted Christians was only 0.4 and 0.1 respectively.A survey on caste by Equality Labs in USA conducted in 2016 among the South East Asian community found that “when surrounded by people of Indian descent — caste bias follows”. The survey also finds that American universities with a large number of South East Asian community members also have a caste status. Read more about the survey here.

60% of Dalit migrants stated that they had faced caste based derogatory jokes, 40% Dalits were made to feel unwelcome at a place of worship and more than half the respondents from the Dalit community mentioned that they faced unfair treatment at the place of work. Read more about the survey findings here. While migrants often become vulnerable by virtue of being migrants, they also come from a prior system of structural oppression which gives birth to multiple marginalisations. Inclusive policy-making that centres the most vulnerable is required.

Within India, the widespread perception is that marriage is the sole driver of female migration. What this dictum overlooks is that most women migrants also work. Even women who migrate overseas to join their husbands are completely overlooked in the narratives of Indian emigrants. Often each member of the migrant household contributes towards remittances sent home.

The benefits of migration can only be reaped when the most vulnerable have the agency and freedom to migrate, and to be able to choose their profession in their destination.

November 2019 Updates!

Our team members Rohini, Aarohi and Geetika published an article on “Exclusionary Policies push Migrants to Cities’ Peripheries” for IndiaSpend. You can read the article here.

Varun wrote an article for India Development Review, titled “Understand migrants’ lives to address their needs”. You can read the article here.

Varun, Priyansha and Rohini wrote on “How State Governments Disfranchise Interstate Migrants in India” for IndiaSpend. Read the article here.

And finally, if you missed our October Newsletter on migrants in the Indian textile sector, you can read it here.We look forward to bringing you more stories, insights and perspectives from the world of migration in the days to come. Until then, please consider supporting us by making a donation. Click here.

*The authors are researchers at India Migration Now, a Mumbai based migration data, policy and research agency

No comments:

Post a Comment