Mathew J. Burrows

Our conclusion in 2016’s Global Risks 2035 was that state-on-state conflict posed a bigger threat than terrorism. In the two years since, the post-Cold War order has continued to unravel without a “new normal” emerging. If anything, with de-globalization underway, conflict among the great powers looms even larger than when Global Risks 2035 was written in mid-2016.

We must recognize that the old historical rhythm that laid the foundations of the Western liberal order has come to an end. The world now faces momentous challenges with climate change, the return of state-on-state conflict and an end to social cohesion with increasing levels of inequality. Without a political, intellectual and, some say, spiritual renaissance that addresses and deals with the big existential tests facing humanity we will not be able to move together into the future.

With so much of the analysis of Global Risks 2035 still on target, this update focuses on key changes since 2016 and the alternative worlds that appear to be emerging from the fraying of the old normal.

A short recap of 2016’s Global Risks 2035

In the best case, we forecast a world headed toward multipolarity with limited multilateralism. At worst, we projected a multipolarity that devolved into another Cold War bipolarity—with China, Russia, and their partners pitted against the United States, Europe, Japan, and other allies. In that scenario, war seemed inevitable.

The fracturing of the post-Cold War global system would be accompanied by internal fraying caused by technological advances. No one was spared. Robotics, artificial intelligence (AI), 3D printing, and automation were already upending both skilled and unskilled occupations in the developed world. As the cost of robots came down and automation and 3D printing spread, still-struggling emerging markets could no longer rely on lower labor costs, as China did to fuel its rise. This is a far cry from the earlier notion that globalization and technological change would “lift all boats.”

Under any scenario, many of the poorest of the developing countries will face stiffer, potentially existential, challenges linked to climate change, poor governance, higher incidences of civil conflict, and overpopulation. Climate change will impact everyone in the coming decades, but the poorest areas—sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia—will be hit hardest by increasing temperatures and rising sea levels.

Tectonic shifts

The United States (US) remains one of the biggest puzzles. The founder of the old order—centered on liberal market values—has become blatantly self-interested and nationalistic under President Donald Trump. At the same time, the United States has become more divided, making it difficult to make any prognostications about future trends post-Trump.

Although it would be a fool’s errand to try to predict whether the US will be Blue (led by the Democratic Party) or Red (run by Republican Party) following the next presidential election in 2020 or beyond, numerous tectonic shifts are shaking the US position in the world and on the home front. Returning to the halcyon days of the 1990s when the United States was at the height of its powers across the board will not be an option for any president.

However much Americans may feel regret or nostalgia, the unipolar moment is definitively over and a multipolar system has become increasingly entrenched. The US has several options for how it can operate in this new situation.

It can deny the inevitable, thereby worsening its ability over time to protect its interests.

It can jockey for advantage as most powers have had to do throughout history, building coalitions to protect its interests and seek advantage.

Russians and Americans generally agree on each country’s changing role in the world over the past 10 years

While the United States will remain among the most powerful actors with significant military and economic leverage, acting as if it can still make all the rules and enforcing them on others is not an option.

The US economy

For the United States, a key weakness going forward is the fiscal outlook. The 2017 tax bill reductions may have spurred a rebound, but most economists believe it will be short lived. Despite the Trump administration’s confidence, the US economy has been settling into a lower band of average annual growth—closer to 2.0-2.2 percent—rather than the more than 3 percent that the president is counting on.

Growing debt

Meanwhile, the annual deficit is rising at record speed. Under even the most optimistic forecast, federal debt rises to a dangerous level of over 118 percent of GDP in 2038. Alternative scenarios—which some experts believe may be more realistic—show even larger annual deficits and overall debt up to as much as 165 percent of GDP by 2038.

Implementing the structural reforms needed to bring down deficits will not be easy. The US is already overspending on healthcare even before the vast majority of the baby boomers have retired. As shown by the polemics over former President Barack Obama’s Affordable Care Act, it would be politically difficult for either party to radically reform the healthcare sector. In the medium term, the US appears to be stuck with its more than 18 percent of GDP going to healthcare—almost twice what other advanced economies pay for it, some achieving better results.

Wars are expensive

Except for the first Gulf War—which was largely paid for through foreign grants—the United States has financed all its wars since the Korean War by borrowing. With the Iraq and Afghanistan Wars costing $7 trillion and still counting, it is hard to imagine any wars of “choice” being an option without setting the US on a path of fiscal ruin.

Further borrowing on the scale required for a major war would raise interest rates and squeeze available money for other uses.

To lower the level of borrowing, the US would probably have to go back to some form of taxation or reduced expenditures elsewhere in the federal budget, cutting Social Security and healthcare. Even a war of necessity might come under added scrutiny, although Americans would undoubtedly be prepared to pay anything to protect themselves.

US global influence

That said, the United States has a lot of maneuvering room if it plays a more restrained hand. Although one recent Atlantic Council study showed how the US has been losing influence, particularly in the developing world, Russia and China may be overplaying their hands.

Power and Influence in a Globalized World outlines the strategic framework of the international system’s capabilities and interactions amongst the global community. The report shows how power and influence are derived from more than just coercive military capabilities, but are exercised through networks of economic, political, and security interactions involving states as well as non-state actors. The function of this report is to fill in the conceptual and empirical gaps, by creating a new index, the Foreign Bilateral Influence Capacity (FBIC) Index. The FBIC is tasked with identifying the key influencers in the international community, and analyzing those that register above or below their weight in the world, altogether clarifying where the United States and others stand in the international system. The FBIC Index is based on the interaction between states, as well as the relative dependence of one state on another.

Both have severe challenges facing them domestically. China’s neighbors worry about a dominant regional power, but they do not want to be forced to choose between Washington and Beijing. It is unclear—despite huge efforts and investments—whether China can make the leap to become an innovative economy in the short time frame (Made in China 2030) that Beijing has in mind.

Americans prefer themselves over China as world leader, but Russians prefer ‘neither’ over the United States

Owing to the slowdown in economic growth, fewer good-paying jobs are available for China’s newly minted middle-class graduates. While AI affords the regime better ways to track dissent, revolutions have occurred before, with the odds stacked against the perpetrators. Although a revolt seems unlikely today, a sustained economic slowdown coupled with growing inequality could change that outlook.

The cycle of globalization and deglobalization

Russia must worry about the decline of key sectors, including its energy sector. Unless it can overcome sanctions and lure more investment, especially from the West, it will be impossible to boost its long-term economic performance. Recent Pew Research polling shows that majorities or pluralities of publics in nearly all the 25 countries surveyed say that the future would be better if the United States was the world’s leading power than if China were. This is despite the fact those publics see the US as having only a slender economic lead over China.

The West still has an advantage in terms of values. Anti-corruption and rule of law are particularly popular, but the US and rest of the West must be careful about lecturing others too much. Owing to increasing nationalism across the world, no leaders want to be told how to run their country’s government or economy. For the moment, engendering growth and providing economic opportunities are more important for the emerging global middle class than establishing a full-bodied Jeffersonian democracy.

“For the moment, engendering growth and providing economic opportunities are more important for the emerging global middle class than establishing a full-bodied Jeffersonian democracy.”

Transitions to a new order are tricky for all powers. In the twentieth century, Germany made a bid to become a hegemonic power, but the world struggle that ensued irreparably wounded Britain while laying the groundwork for the US to become the global superpower. Few, if any, observers predicted such an outcome at the start of the twentieth century. An absolute US decline is not inevitable, but there is no guarantee against it. In the same way that both Germany and Britain suffered, a conflict with today’s rising power—China—would increase the risks of decline for the United States.

Finding a way for both the United States and China to avoid a Thucydides trap is likely to be beneficial to US interests even if doing so means conceding increased status for China in the global order. The mindset of US foreign policy elites is some ways away from accommodating itself to a world in which both the US and China rule—a world in which compromises must be made. Almost seventy years after world power fell suddenly on US shoulders, a new generation will have to go back to the drawing board to figure out a new world order in which US and Chinese interests can both be assured while not laying the groundwork for an eventual conflict.

Technology: A game changer for good and bad

The Sino-US technology rivalry is increasingly implicated in the broader spurt toward a multipolar world. Even five years ago, the United States’ innovation lead appeared assured, although the Atlantic Council published warnings about the need to bolster the investments in basic research, including the desirability of boosting US human capital investments.

The Atlantic Council’s 2012 report Envisioning 2030: US Strategy in a Post-Western World, written as a companion piece with the US National Intelligence Council’s Global Trends 2030: Alternative Worlds, stated, “the keystone of national power remains US economic strength and innovation.” Building upon this statement, this year’s Envisioning 2030: US Strategy for the Coming Technology Revolution, edited by Strategic Foresight Initiative Director Mathew J. Burrows, explores the consequences of major disruptions that will be caused by emerging technologies and recommends that the United States must prepare now if it wants to remain competitive on the global stage.READ MORE

Only a few years later, many experts are talking about China leading in certain areas—such as AI-based facial recognition technologies—and having an advantage because of its big stores of data, necessary to perfecting AI algorithms.

It is too soon to say which country will win. In the view of many Chinese, the United States has such built-in advantages that it will take China decades more before it can match the US, let alone surpass it. For their part, some US experts believe that China has a distinct advantage in that its civilian research and development (R&D) is more closely aligned with its military sector, allowing it to more rapidly exploit the dual-use possibilities of AI, robotics, and other emerging technologies.

How the competition develops poses broader questions for global development in the coming decades. If the technology sectors are increasingly protected in the United States, China, and other countries, the result will be fragmentation, diminishing globalization. Experts already fear that separate 5G standards might be developed for the US, European Union (EU), and China, forcing the rest of the world to choose among them.

China has its Great Firewall for the internet. The EU is setting privacy standards that are not being adopted in the US. A balkanization of the internet—which many experts, including those at the Atlantic Council, have feared could happen—appears increasingly likely.

Such a breakup mirrors the regionalization that has been occurring in trade patterns such that more regionalized trading spheres are becoming divided from each other by conflicting technology standards. Should the globalized science and technology (S&T) expert community become more nationalized, the risk of returning to a type of Cold War rivalry and turning technology into a vehicle for national economic and military advantage would increase—a significant departure from the original internet founders’ dream of bringing together disparate peoples.

Globally, up to 375 million workers may need to switch occupational categories

Whether countries will move away from broad cooperation toward increasing competition is an open question. Multinational businesses—Western and Chinese—still want to operate in global markets. The S&T research communities remain highly international with the best Chinese scientists being trained in the United States and the most important patents being developed by international teams.

Changing immigration: Benefits and dangers

Aging and migration are creating a new dynamic. The assumption has often been that more development in the places that migrants are coming from will lessen their desire to emigrate. Apparently, though, it is the other way around. Economic development leads to more migration until the country sending migrants develops to a point that there are high-skilled jobs at home.

GDP per capita and emigration

The net flow of migrants from Mexico to the US has reversed in recent years, for example, because there are now many more economic opportunities in Mexico than before. Migrants want better educational opportunities and jobs that can improve their skill levels. This new trend toward increased mobility and migration mirrors the growth in the global middle class.

For their part, aging countries are in need of labor, particularly highly skilled workers. Japan, Germany, and China all have growing economies and quickly aging nativist populations. Japanese Prime Minister Shinzō Abe is exploring a pathway for immigrants to become Japanese citizens—a startling departure from Japan’s traditional aversion. Japan is already letting in more guest workers. Germany—which will probably benefit demographically from the recent increased migration in the medium-to-long-term future—has been exploring how to attract more highly skilled workers. Like their Japanese counterparts, German companies have relocated operations elsewhere to draw in new skilled workers. China is also trying to re-attract its diaspora and other non-Chinese to come and work in China. Skills gaps have become a permanent challenge in Shanghai and other fast-growing urban areas.

Populism and immigration

The political debates over immigration have largely obscured this phenomenon, casting the spotlight on the negative features of immigration, particularly the deepening social divides fueling populism.

Right more likely to see immigrants as economic burden

Establishment political parties in many Western countries have taken a hit because their base supporters are opposed to immigration. Closing down all immigration risks economic decline for Western countries, whose aging will accelerate. Over time, though, competition for highly skilled immigrants could increase as aging accelerates and countries try to deal with the widening skills gaps. Even the Trump administration, which has gotten political advantage from its anti-immigration rhetoric, wants more highly skilled workers coming to the United States (although the general anti-immigrant rhetoric is making that harder to bring about).

The changing face of America, 1965–2065

Refugees

Refugees are a separate category of migrants that are afforded more rights and protections in international law. Even before the Syrian civil war, a higher proportion of civilians than in decades past was fleeing conflicts.

Nevertheless, many richer countries have not had the capacity or willingness to take Syrian refugees despite their many promises.

Trump wants to put up a wall to discourage low-skilled immigrants and refugees.

European countries want to establish refugee centers in North Africa, restraining illegal entry into the EU.

All of this amounts to good and bad news for those wishing to emigrate. The better educated have the best chance. Although deserving, refugees will find it harder to make their case for entry into Western countries.

Climate change—A sleeper awakening?

Experts have been warning about the impacts of climate change for years—if not decades. The temptation—especially when the impacts are less widespread—is to take small steps toward managing the risks. Research is now showing that the world is on the verge of a tipping point, after which no practicable amount of effort can reduce the risk of a slide to a plus-2-degree C world in which life would become unbearable for a great many.

1.5° C2° C2° C

EXTREME HEAT

Global Population exposed to severe heat

at least once every five years 14% 37% 2.6X

WORSE

SEA-ICE-FREE ARCTIC

Number of ice-free summers AT LEAST 1 EVERY

100 YEARS AT LEAST 1 EVERY

10 YEARS 10x

WORSE

SEA LEVEL RISE

Amount of sea level rise by 2100 0.40 METERS 0.46 METERS 0.06M

MORE

SPECIES LOSS

VERTEBRATES

Vertebrates that lose at least half of their range 4% 8% 2x

WORSE

SPECIES LOSS PLANTS

Plants that lose at least half of their range 8% 16% 2x

WORSE

SPECIES LOSS INSECTS

Insects that lose at least half of their range 6% 18% 3x

WORSE

ECOSYSTEMS

Amount of Earth’s land area where ecosystems

will shift to a new biome 7% 13% 1.86x

WORSE

PERMAFROST

Amount of Arctic permafrost

that will thaw 4.8

MILLION KM2 6.6

MILLION KM2 38%

WORSE

CROP YIELDS

Reduction in maize harvests in tropics 3% 7% 2.3x

WORSE

CORAL REEFS

Further decline in coral reefs 70–90% 99% UP TO

29%

WORSE

FISHERIES

Decline in marine fisheries 1.5

MILLION TONNES 3

MILLION TONNES 2x

WORSE

Part of the problem has been that those living in the most deprived parts of the world will experience the most suffering. Restricting carbon emissions could disadvantage emerging markets, such as India, that are beginning their climb to economic modernization, including consuming more energy.

The temptation for India and other developing states will be to use cheap coal to power their rise, dooming themselves and others.

Coal consumption by region

From an equity standpoint, the US cannot forbid the use of coal by others without undermining the moral position of the West, whose rapid development over the past couple centuries was partly linked to the use of coal. Ramping up assistance by the advanced economies could solve this problem by enabling the early adoption by developing countries of renewable energy sources and natural gas.

Such a climate change Marshall Plan seems politically impossible—at least for the moment—but such a plan is conceivable if the effects of climate change become more evident.

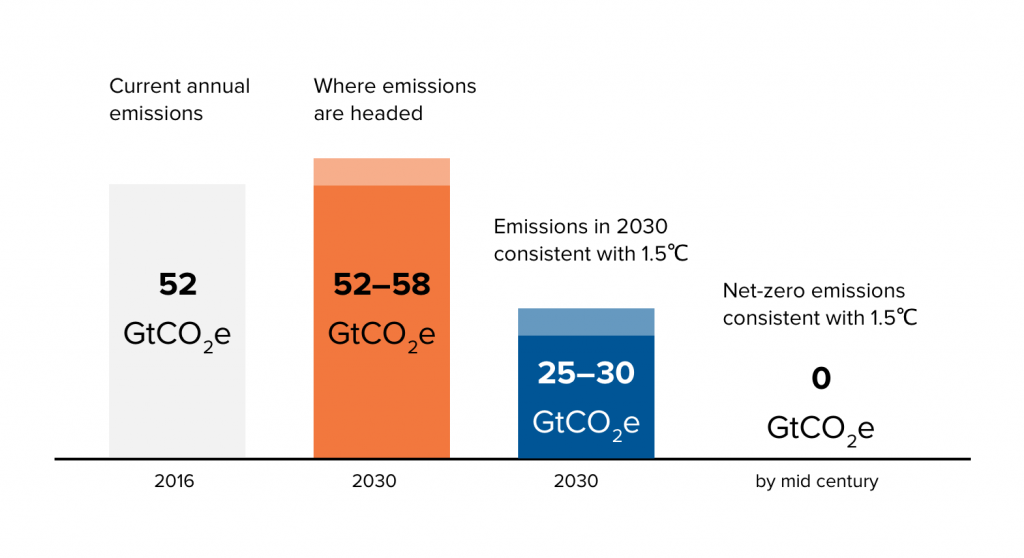

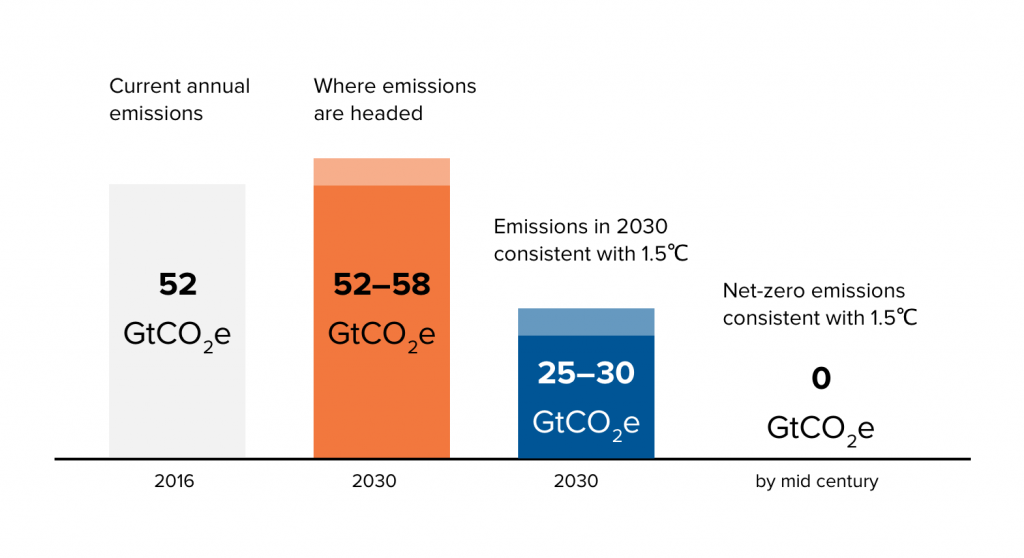

The world is not on track to limit temperature rise to 1.5 C Source: World Resources Institute, October 2018

Source: World Resources Institute, October 2018

Source: World Resources Institute, October 2018

Source: World Resources Institute, October 2018

A greater number of extreme weather events than were predicted at this point in the climate change cycle are already occurring. A crescendo of more massive hurricanes and cyclones, exceedingly hot summers or cold winters, devastated harvests, and other manifestations of severe climate change effects might convince policy makers and publics in a way that scientists have not been able to do thus far.

If that were the case, a massive collective program to solve an upcoming existential threat—and it has to be collective if it will be effective—would have a spillover effect, ushering in a new period of global cooperation. Historically, spurts in global cooperation have occurred after massive failures of the global system—such as after the Napoleonic Wars or the Second World War. However, the world cannot wait until the impacts of climate change are full blown. By that time, the world most likely would descend into a sauve qui peut—every country for itself—posture.

With some foresight, though, the worst outcome can be forestalled and advantages can be gained in other areas by building global cooperation.

Scenarios: The bad, the good, and the ugly

Of the three scenarios outlined in the main text, A New Bipolarity—marked by a US-China rivalry—appears to be the one the world is slipping into. Yes, the global players should have learned the lessons of the old Cold War, and nobody wants to return to another, but the obstacles to A New Bipolarity are eroding. At the core is a growing protectionism throughout the world.

A new bipolarity

Two economic spheres—China at the core in one and the US and Europe in the other—are shaping the global economy. The more that two-way investment is cut by both the United States and China, the greater the chance of an eventual conflict. Militarily, both sides see the other as an enemy. Added to the economic competition is a new layer with the proponents on each side having vested interests in militarily arming against the others—a new version of the Anglo-German naval rivalry before World War I.

Disturbingly, the narratives on both sides are already forming. For Americans, the narrative, which has widespread bipartisan support, revolves around “China owes us.” The Chinese would never have risen without the US allowing them in the World Trade Organization (WTO) and opening the global trading system. That mindset, of course, ignores all the benefits that the United States has derived from China becoming a global economic driver, including preventing the West from sliding into a deeper recession after 2008. For their part, the Chinese maintain an even more deeply rooted assumption that the US will try to stop China from rising at some point in order to preserve the United States’ global position.

To overcome distrust, bold leadership will be required on both sides. In her magisterial study of the period leading up to the World War I, British historian Margaret Macmillan highlighted the notable lack of leadership that failed to stop the creep toward war. Similarly, Professor Christopher Clark at the University of Cambridge entitled his book on the same period The Sleepwalkers. The difficulty for both sides in finding an accommodation derives partly from the diverging systems operating in each country. China is wedded more than ever to a large state sector, while US strength comes from a vibrant private sector. Without better US and Western access to China’s growing market, a high point may have been reached in the Chimerica embrace of the last couple decades.

“China is wedded more than ever to a large state sector, while US strength comes from a vibrant private sector.”

The US and other Western governments are ready to limit Chinese access to sensitive technology sectors because of increasing concerns about intellectual property (IP) loss to Chinese competitors. Increasing restrictions on both sides promote distrust and even enmity. Strong leadership will be required to prevent this situation from devolving into a bipolar global order—with far-reaching implications for the rest of the world. Asian countries, particularly, do not want to choose. A bipolar world with its increasing protectionist barriers would probably mean less growth, slowing the potential for emerging market countries to develop.

World restored

China has traditionally learned from its mistakes, making course corrections along the way. In the United States, many domestic voices are warning against the increasing protectionist course. In the World Restored scenario, the US, China, and others pull back from bipolarity. The slower growth experienced everywhere as barriers go up stirs popular unrest, pushing G20 governments after an initial period of disarray to reform global trade. The United States’ containment policy against China eventually becomes too costly; for its part, the Chinese government’s gambit of accelerating innovation while suppressing freedoms hits a brick wall with slower-than-expected advances toward the development of new technologies.

In this scenario, the middle classes in both countries play a key role in shaping the future. All want improvements in economic opportunity for their children. Getting into a tit-for-tat rivalry has little appeal if slower growth is the consequence. Chinese President Xi Jinping is eased out and nationalist governments in the West go down in defeat due to a long period of underwhelming growth. After years in which trade has become more regionalized, a new global trade round is agreed to by the G20 to re-energize global trade and growth.

“The middle classes in the United States and China…want improvements in economic opportunity for their children.”

Global challenges such as climate change and failing states are also a factor, spurring cooperation. Such cooperation leads major powers to engage in more concerted and coordinated peace-building. The leading powers eventually get to the point of agreeing on global defense spending curbs, successfully negotiating new international conventions on banning or limitation of space, biological, and cyber weapons. The peace that results is still fragile, however. Political reform inside China and the West is a prerequisite for a permanent transition to a more peaceful world.

A descent into chaos

The third scenario—A Descent into Chaos—is the worst one. It is driven less by the dynamics surrounding the US-China relationship than by a widespread economic meltdown that is triggered by China suffering a deep economic reversal. The economic turmoil spreads first to China’s trading and investment partners in the Global South. The Chinese government teeters, as do many in the developing world. Although a partial recovery occurs over time, high global growth rates do not return. Protectionism spreads and many countries maintain capital controls after the economic crisis has dissipated.

Even before the Chinese reversal, the US has been tightening its restrictions on Chinese investment in its high-technology sector, curbing the number of Chinese students able to study science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) subjects at leading US universities.

12%

Percentage of doctorates awarded to Chinese students in STEM fields by United States universities in 2017.

National Science Foundation Survey of Earned Doctorates

With China’s slowdown, growth in the US and other advanced economies is also hit and the trend toward protectionism is reinforced.

This scenario encompasses more than economic collapse, though it is a key driver. With political instability spreading, conflict and violence increase. Under public pressure to pull back, the US president withdraws the US presence from the Middle East. Soon a hot war breaks out between Iran and Saudi Arabia and its ally, Israel. Elsewhere, a vicious cycle of authoritarianism leading to revolution spins, followed by a reassertion of even harsher rule and suppression.

Is there any way to stop the descent? No leader believes he or she has the means to stop it. At home in all the major powers, growing populism, nativism, and jingoism come to the fore, militating against saving the world.

Strategic foresight needed more than ever

The earlier Global Risks 2035 made a plea for leadership. This volume repeats that demand, but adds that better integration of strategic foresight into decision making is needed. Governance will remain difficult so long as it is about crisis management.

To respond to the changing world, we need a new strategy—one that is both ambitious and innovative, geared towards meeting the challenges and opportunities that the new decade brings. In this Atlantic Council Strategy Paper, Present at the Re-Creation, Ash Jain and Matthew Kroenig propose exactly that: a visionary but actionable global strategy for revitalizing, adapting, and defending the rules-based international system.READ MORE

Flabbergasted by surprising events, governments have stumbled from crisis to crisis: the financial meltdown (2007/2008), the collapse of Libya and Syria (2010-), the nuclear disaster in Fukushima (2011), the conflict in Ukraine and the annexation of the Crimea by Russia (2014-), the rise of the so-called Islamic State and the proclamation of the Caliphate (2014), the wave of migrants from the Greater Middle East to Europe (2015-), Brexit (2016), and Donald Trump’s victory in the US Presidential elections (2016).

U.S. President Donald Trump and Russia’s President Vladimir Putin shake hands as they meet in Helsinki, Finland July 16, 2018.

Instead of being able to implement visionary and forward-looking strategies, policymakers are being driven by events. The consequence is a widespread feeling of uncertainty up to the highest echelons of the public and private sectors. Leadership throughout the West is in crisis. In their seminal report “Thinking the Unthinkable,” Nik Gowing and Chris Langdon adequately describe this uneasy situation in detail. Their analysis is sobering:

“A proliferation of ‘unthinkable’ events … has revealed a new fragility at the highest levels of corporate and public service leaderships. Their ability to spot, identify and handle unexpected, non-normative events is shown not just to be wanting but also perilously inadequate at critical moments. The overall picture is deeply disturbing.”

But even more troubling is the inactivity of leaders despite their collective experience of numbness in all of the above-mentioned crises. “Remarkably, there remains a deep reluctance, or what might be called ‘executive myopia’, to see and contemplate even the possibility that ‘unthinkables’ might happen”, Gowing and Langdon summarize the state of affairs—“let alone how to handle them.”

“Remarkably, there remains a deep reluctance, or what might be called “executive myopia,” to see and contemplate even the possibility that “unthinkables” might happen.”

The challenges of this new world leave us in increasing need of orientation in what is unfamiliar terrain: the fluctuating global economy, epidemics such as Ebola, cyber security, hybrid warfare, the redesign of regional orders (Sykes-Picot, ‘One Road-One Belt’, Eurasia Economic Union as the most-telling examples)—all these are ‘wicked problems’ that defy linear solutions or adhere to recipes of our grandparents’ cooking books.

For seven decades, free nations have drawn upon common principles to advance freedom, increase prosperity, and secure peace. Free nations must adapt and change. Yet our principles remain sound because they reflect the common aspirations of the human spirit. Inspired by the inalienable rights derived from our ethics, traditions, and faiths, we commit ourselves to seek a better future for our citizens and our nations.READ MORE

At the same time, the geopolitical order changes irreversibly. Since a quarter of a century we have been talking about the rise of new powers (e.g., the so-called BRICS—Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa), the decline of the Bretton Woods system, and the dawn of polycentrism. We have described the impact of globalization from Wall Street to Main Street and back; we analyzed increasing state fragility, even state failure.

But we only started to react when things got so bad that they couldn’t be ignored any longer or when spill-over effects—such as the wave of Syrian refugees coming to Europe in 2015—affected us directly.

Even worse is our handling of long-term trends:

Climate change

Rising world population

Demographic change

Urbanization

Non-sustainable consumption patterns of a rising global middle class.

Addressing these wicked problems of global dimensions demands lateral, not linear, thinking. Government on auto-pilot will not be sufficient any longer, nor muddling through or constant crisis management.

Ignorance, indifference, or inability can have far-reaching consequences in our uncertain and surprise-laden world. To live up to the task, our societies need to invest in strategic foresight and enhanced capabilities for anticipatory governance. Thinking in alternative plausible futures is a prerequisite to build up resilience in a constantly changing environment.

This demands a fundamental review of the roles that government and political administration are expected to play. We all know that ‘the state’ is no longer an omnipresent, omniscient, infallible Leviathan. But it is the only institution capable of establishing stability and order in a globalized world—if necessary with coercive means.

To reinstate the state, including regional and multilateral institutions, in this uncertain world as an effective instrument for forming opinion and consensus in society as a whole, government institutions need to see themselves as learning, co-creative systems. This is a precondition if they are to develop strategic ability and proactively plan for the future. Conversely, inertia, fear of change and lack of courage result in risks being identified too late and opportunities squandered.

Without such reforms of the role of the state, decline is inevitable. With refurbished governments and multilateral institutions interested in seeing beyond the next crisis and committed to cooperating with others, we have a chance for a new renaissance.

No comments:

Post a Comment