By SYDNEY J. FREEDBERG JR

Army 8×8 Stryker (left) and Humvees (right), all mounting variants of the hastily fielded Saber Fury electronic warfare system — note the veritable forest of antennas.

Army 8×8 Stryker (left) and Humvees (right), all mounting variants of the hastily fielded Saber Fury electronic warfare system — note the veritable forest of antennas.

AOC: Pentagon policymakers — prodded by Congress — are taking electronic warfare seriously again. But reforms at the top will take years to trickle down to tangible improvements for the troops.

“I see a lot of good work being done in OSD, Joint Staff, and the services, but I would say it’s early,” Rep. Don Bacon told me and another reporter on the sidelines of the annual Association of Old Crows electronic warfare conference. “I think we turned the corner, but we’re still on first base…. We’ve got a long ways to go.

Then-Brig. Gen. Bacon celebrates his “fini flight” before leaving command.

From 2014 To Today

While the Navy and Marines retained their jammers, the Army and Air Force largely disbanded their EW forces after the Cold War. A retired Air Force one-star and electronic warrior himself, Bacon recalled that “I was angry when l was active duty because I thought we walked away from the best EW doctrine and capabilities in the early 90s. When I retired, we were second or third best.”

Bacon retired in 2014, the same year the Defense Science Board’s Paul Kaminiskicame to AOC to sound the alarm on electronic warfare. Just weeks before, senior research & engineering official Alan Shaffer had bluntly announced, “we have lost the electromagnetic spectrum.”

Alan Shaffer

How far have we come? At this year’s conference, Shaffer – now promoted to the principal deputy undersecretary for acquisition after four years in France working with European allies– sounded slightly less grim. “We are in a fight for the electromagnetic spectrum, and I’m not sure we’re winning,” he said this week.

How far have we come? At this year’s conference, Shaffer – now promoted to the principal deputy undersecretary for acquisition after four years in France working with European allies– sounded slightly less grim. “We are in a fight for the electromagnetic spectrum, and I’m not sure we’re winning,” he said this week.

Unlike the US in the 1990s, “Russia never stopped doing electronic warfare,” Shaffer continued. They’re now confident enough of their abilities, he said, to actively jam GPS during NATO exercises: “My assessment when I was in NATO from 2015 to 2018 was, they’re darn good. China’s also very good.”

That sounds an awful lot like the US is still, as Rep. Bacon thought five years ago, “second or third best.”

Bacon, who’s crusaded in Congress for EW improvements, does see substantial progress. “I’m really excited when I look at where we were at three years ago, where we did not have a plan, we did not have a vision,” he said. Since then, the Office of the Secretary of Defense has created a high-level Executive Committee to advance electronic warfare and published its first-ever EW strategy, the Air Force launched a task force to study the problem, the Army announced plans to for new EW units and equipment, and Congress ordered the Pentagon to create an Electromagnetic Spectrum Operations Cross Functional Team that’s now looking at potential reforms.

“They’re analyzing how they want the structure,” Bacon said. “They’re still debating this,” he said, but he expects the Cross Functional Team to recommend: a senior civilian position responsible for all electronic warfare, perhaps an assistant secretary; new uniformed EW leadership on the Joint Staff; and enhancements to Strategic Command’s (largely toothless) role as lead operational advocate for EW.

“I’m not too worried about it’s got to be in this office or that office. I just want to know who’s in charge,” Bacon said. “We’ve gone decades with nobody in charge.”

BAE Systems graphic of their new EC-37B Compass Call, with the current EC-130H model in the background.

“Time To Start Moving Out”

Of course, getting organized to tackle the problem is not the same as actually solving the problem. “There’s a lot of good talk going on,” Bacon said, “[but] you can talk for decades, it’s time to start moving out…. We want to start seeing action.”

The Navy and Marines are building on their traditional strengths in electronic warfare, which they never gave away, but the land-based services are building up from very little. The Air Force is betting heavily on the heavily classified capabilities of the new F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, and it’s upgrading its Compass Call aircraft from aging EC-130 turboprops to modified Gulfstream jets, but the service is still pondering its overall approach. The Army has a clear plan, but it will take years to train the highly specialized personnel and build the new equipment to build its proposed EW units.

Navy EA-18G Growler with jamming pods

Speed is crucial, Shaffer told the AOC conference. “If we’re taking 10 to 15 years to field an EW system, by the time it’s fielded, it will be obsolete,” he said. “We’re at the point now where we are in a contest for digital supremacy and we have to go faster. We have to figure out how to upgrade systems quickly.” That’s not something the traditional defense acquisition system is designed to do.

Speed is crucial, Shaffer told the AOC conference. “If we’re taking 10 to 15 years to field an EW system, by the time it’s fielded, it will be obsolete,” he said. “We’re at the point now where we are in a contest for digital supremacy and we have to go faster. We have to figure out how to upgrade systems quickly.” That’s not something the traditional defense acquisition system is designed to do.

There are benefits to a deliberate process with extensive planning and testing before you buy, Shaffer acknowledged. If you’re buying platforms that are meant to stay in service for decades and cost “multiple billions of dollars… I’m not going to go fast,” he said. But if you’re upgrading the electronics and software that go on those platforms – in other words, the components that actually do electronic warfare — “I have to go fast,” he said. “I have to go fast in open systems but do it in a smaller chunks.”

In other words, you want to design your big, long-lasting systems to be easily upgraded with new subsystems – an approach known as open architecture – and then make lots of small, rapid upgrades over time. “The ability to build in small, small increments is absolutely critical,” Shaffer said, and new authorities granted by Congress such as so-called Section 804 middle-tier acquisition made that much more possible.

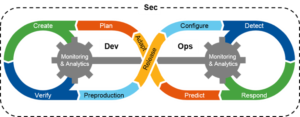

A diagram of the DevSecOps (Development – Security – Operations) model for developing software.

The big remaining hurdle, however, is software development. The Pentagon process has clearly distinct stages for developing a new system, testing it, and fielding it, each funded by a separate congressionally-controlled account that can only be used for that specific purpose – what’s known as “colors of money.” Silicon Valley, by contrast, has embraced an approach called Agile or DevOps, in which developers crank out a bare-bones version of the software – the “minimum viable product” – and quickly hand it to real users, who give feedback the developers then use for the next upgrade, which they hand right back to the users for more feedback that drives more upgrades in a rapid cycle. (A common variant, DevSecOps, brings cybersecurity experts into the mix to ensure the software is secure as well as functional).

The big remaining hurdle, however, is software development. The Pentagon process has clearly distinct stages for developing a new system, testing it, and fielding it, each funded by a separate congressionally-controlled account that can only be used for that specific purpose – what’s known as “colors of money.” Silicon Valley, by contrast, has embraced an approach called Agile or DevOps, in which developers crank out a bare-bones version of the software – the “minimum viable product” – and quickly hand it to real users, who give feedback the developers then use for the next upgrade, which they hand right back to the users for more feedback that drives more upgrades in a rapid cycle. (A common variant, DevSecOps, brings cybersecurity experts into the mix to ensure the software is secure as well as functional).

In DevOps, development, testing, and fielding blur together in a way the current Pentagon system just can’t handle – and if officials can’t clearly account for each dollar, showing that (say) money appropriated for testing went only for testing and nothing else, they may have broken the law.

“We have to have authority to use one color of money for testing, development, and deployment, and we’re going to see how that works,” Shaffer said, with at least a dozen different pilot projects trying out the new approach to software development. Feedback from those experiments will shape the Pentagon’s long-term plan for reform.

“If we don’t get it right, I’m sure Congress will help us,” Shaffer said. Rep. Bacon and his allies will certainly be watching.

No comments:

Post a Comment