by Lindsay Maizland

Human rights organizations, UN officials, and many foreign governments are urging China to stop the crackdown. But Chinese officials maintain that what they call vocational training centers do not infringe on Uighurs’ human rights. They have refused to share information about the detention centers, and prevented journalists and foreign investigators from examining them. However, internal Chinese government documents leaked in late 2019 have provided important details on how officials launched and maintain the detention camps.

Human rights organizations, UN officials, and many foreign governments are urging China to stop the crackdown. But Chinese officials maintain that what they call vocational training centers do not infringe on Uighurs’ human rights. They have refused to share information about the detention centers, and prevented journalists and foreign investigators from examining them. However, internal Chinese government documents leaked in late 2019 have provided important details on how officials launched and maintain the detention camps.

When did mass detentions of Muslims start?

Some eight hundred thousand to two million Uighurs and other Muslims, including ethnic Kazakhs and Uzbeks, have been detained since April 2017, according to experts and government officials [PDF]. Outside of the camps, the eleven million Uighurs living in Xinjiang have continued to suffer from a decades-long crackdown by Chinese authorities.

Most people in the camps have never been charged with crimes and have no legal avenues to challenge their detentions. The detainees seem to have been targeted for a variety of reasons, according to media reports, including traveling to or contacting people from any of the twenty-six countries China considers sensitive, such as Turkey and Afghanistan; attending services at mosques; and sending texts containing Quranic verses. Often, their only crime is being Muslim, human rights groups say, adding that many Uighurs have been labeled as extremists simply for practicing their religion.

Hundreds of camps are located in Xinjiang. Officially known as the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region, the northwestern province has been claimed by China since the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) took power in 1949. Some Uighurs living there refer to the region as East Turkestan and argue that it ought to be independent from China. Xinjiang takes up one-sixth of China’s landmass and borders eight countries, including Pakistan, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan.

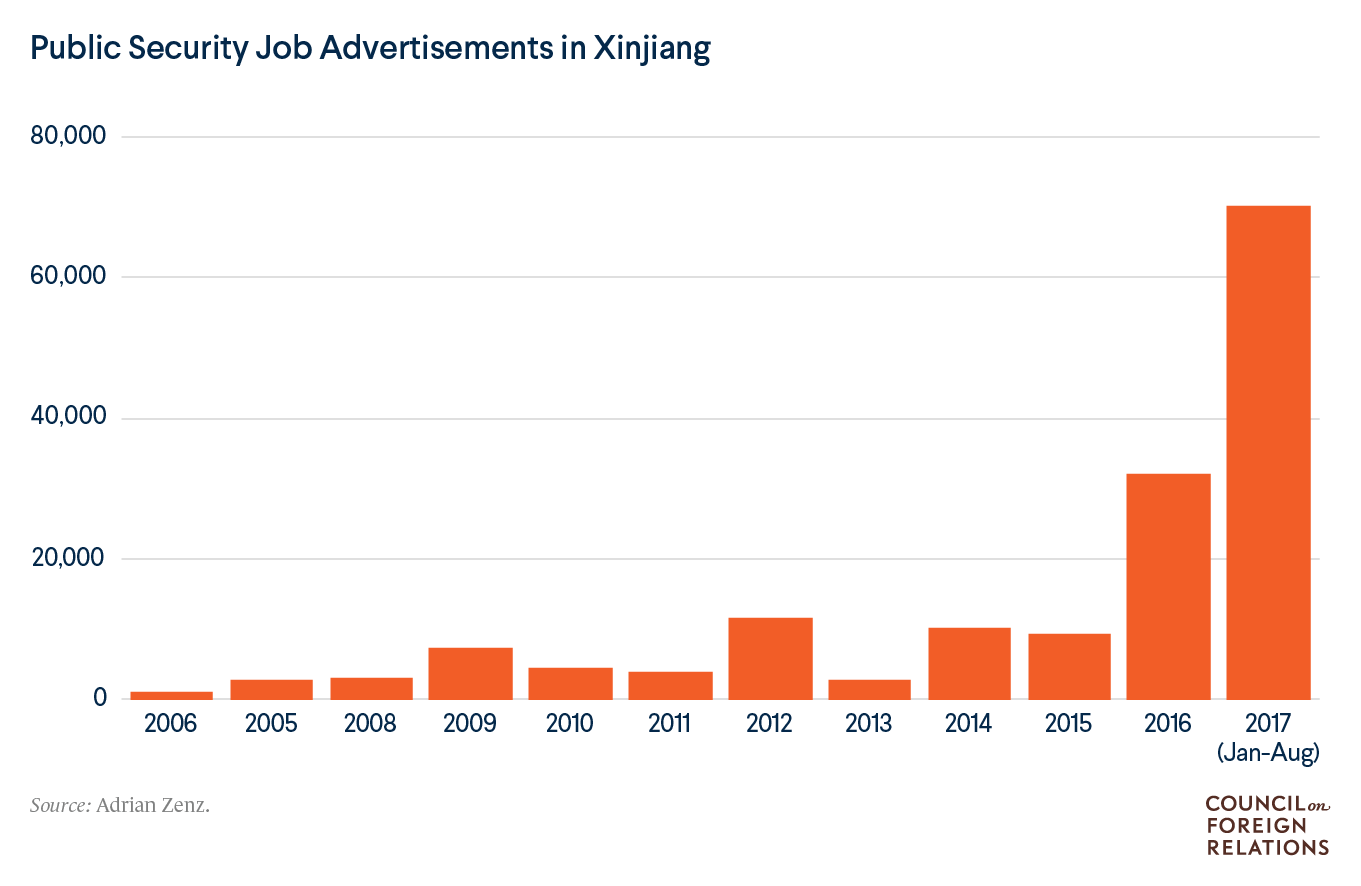

Experts estimate that Xinjiang reeducation efforts started in 2014 and were drastically expanded in 2017. Reuters journalists, observing satellite imagery, found that thirty-nine of the camps almost tripled in size between April 2017 and August 2018; they cover a total area roughly the size of 140 soccer fields. Similarly, analyzing local and national budgets over the past few years, Germany-based Xinjiang expert Adrian Zenz found that construction spending on security-related facilities in Xinjiang increased by 20 billion yuan (around $2.96 billion) in 2017.

What is happening in the camps?

Information on what actually happens in the camps is limited, but many detainees who have since fled China describe harsh conditions. Detainees are forced to pledge loyalty to the CCP and renounce Islam, they say, as well as sing praises for communism and learn Mandarin. Some reported prison-like conditions, with cameras and microphones monitoring their every move and utterance. Others said they were tortured and subjected to sleep deprivation during interrogations. Women have shared stories of sexual abuse, with some saying they were forced to undergo abortions or have contraceptive devices implanted against their will. Some released detainees contemplated suicide or witnessed others kill themselves.

Detention also disrupts families. Children whose parents have been sent to the camps are often forced to stay in state-run orphanages. Uighur parents living outside of China often face a difficult choice: return home to be with their children and risk detention, or stay abroad, separated from their children and unable to contact them.

Why is China detaining Uighurs in Xinjiang now?

Chinese officials are concerned that Uighurs hold extremist and separatist ideas, and they view the camps as a way of eliminating threats to China’s territorial integrity, government, and population.

President Xi Jinping warned of the “toxicity of religious extremism” and advocated for using the tools of “dictatorship” to eliminate Islamist extremism in a series of secret speeches while visiting Xinjiang in 2014. In the speeches, revealed by the New York Times in November 2019, Xi did not explicitly call for arbitrary detention but laid the groundwork for the crackdown in Xinjiang.

Arbitrary detention became widely used by regional officials under Chen Quanguo, Xinjiang’s Communist Party secretary, who moved to the province in 2016 after holding a top leadership position in Tibet. Known for increasing the number of police and security checkpoints, as well as state control over Buddhist monasteries in Tibet, Chen has since dramatically intensified security in Xinjiang. He repeatedly called on officials to “round up everyone who should be rounded up,” according to the New York Times report.

In March 2017, Xinjiang’s government passed an anti-extremism law that prohibited people from growing long beards and wearing veils in public. It also officially recognized the use of training centers to eliminate extremism.

Workers walk along the fence of a likely detention center for Muslims in Xinjiang Province on September 4, 2018. Thomas Peter/Reuters

Under Xi, the CCP has pushed to Sinicize religion, or shape all religions to conform to the officially atheist party’s doctrines and the majority Han-Chinese society’s customs. Though the government recognizes five religions—Buddhism, Catholicism, Daoism, Islam, and Protestantism—it has long feared that foreigners could use religious practice to spur separatism.

The Chinese government has come to characterize any expression of Islam in Xinjiang as extremist, a reaction to past independence movements and occasional outbursts of violence. The government has blamed terrorist attacks on the East Turkestan Islamic Movement, a separatist group founded by militant Uighurs, in recent decades. Following the 9/11 attacks, the Chinese government started justifying its actions toward Uighurs as part of the Global War on Terrorism. It said it would combat what it calls “the three evils”—separatism, religious extremism, and international terrorism—at all costs.

In 2009, rioting in Xinjiang’s capital, Urumqi, broke out as mostly Uighur demonstrators protested against state-incentivized Han Chinese migration in the region and widespread economic and cultural discrimination. Nearly two hundred people were killed, and experts say it marked a turning point in Beijing’s attitude toward Uighurs. In the eyes of Beijing, all Uighurs could potentially be terrorists or terrorist sympathizers.

During the next few years, authorities blamed Uighurs for attacks at a local government office, train station, and open-air market, as well as Tiananmen Square in Beijing. The government also feared that thousands of Uighurs who moved to Syria to fight for various militant groups, including the self-proclaimed Islamic State, after the outbreak of civil war in 2011 would return to China and spark violence.

Are economic factors involved in this crackdown?

Xinjiang is an important link in China’s Belt and Road Initiative, a massive development plan stretching through Asia and Europe. Beijing hopes to eradicate any possibility of separatist activity to continue its development of Xinjiang, which is home to China’s largest coal and natural gas reserves. Human rights organizations have observed that the economic benefits of resource extraction and development are often disproportionately enjoyed by Han Chinese, and Uighur people are increasingly marginalized.

Many people who were arbitrarily detained have been forced to work in factories close to the detention camps, according to multiple reports [PDF]. Researchers from the Center for Strategic and International Studies say forced labor is an important element of the government’s plan for Xinjiang’s economic development, which includes making it a hub of textile and apparel manufacturing.

What do Chinese officials say about the camps?

Government officials first denied the camps’ existence. Starting in October 2018, officials started calling them centers for “vocational education and training programs.” In March 2019, their official name became “vocational training centers,” and Xinjiang’s governor, Shohrat Zakir, described them as “boarding schools” that provide job skills to “trainees” who are voluntarily admitted and allowed to leave the camps. But documents leaked in late 2019 showed how officials worked to repress Uighurs, lock them in camps, and prevent them from leaving.

Chinese officials publicly maintain that the camps have two purposes: to teach Mandarin, Chinese laws, and vocational skills, and to prevent citizens from becoming influenced by extremist ideas, to “nip terrorist activities in the bud,” according to a government report. Pointing out that Xinjiang has not experienced a terrorist attack since December 2016, officials claim the camps have prevented violence.

The government has resisted international pressure to allow in outside investigators, saying anything happening inside Xinjiang is an internal issue. It denies that people are forced to denounce Islam, are detained against their will, and experience abuse in the camps. In early 2019, it organized several trips for foreign diplomats to visit Xinjiang and tour a center; a U.S. official criticized them as “highly choreographed.”

What is happening outside the camps in Xinjiang?

Even before the camps became a major part of the Chinese government’s anti-extremism campaign, the government was accused of cracking down on religious freedom and basic human rights in Xinjiang.

Experts say Xinjiang has been turned into a surveillance state that relies on cutting-edge technology to monitor millions of people. Under Xinjiang’s Communist Party leader, Chen, Xinjiang was placed under a grid-management system, as described in media reports, in which cities and villages were split into squares of about five hundred people. Each square has a police station that closely monitors inhabitants by regularly scanning their identification cards, taking their photographs and fingerprints, and searching their cell phones. In some cities, such as western Xinjiang’s Kashgar, police checkpoints are found every one hundred yards or so, and facial-recognition cameras are everywhere. The government also collects and stores citizens’ biometric data through a required program advertised as Physicals for All.

Much of that information is collected into a massive database, known as the Integrated Joint Operations Platform, which then uses artificial intelligence to create lists of so-called suspicious people. Classified Chinese government documents released by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) in November 2019 revealed that more than fifteen thousand Xinjiang residents were placed in detention centers during a seven-day period in June 2017 after being flagged by the algorithm. The Chinese government called the leaked documents “pure fabrication” and maintained that the camps are education and training centers.

Many aspects of Muslim life have been erased, journalists reporting from Xinjiang have found. Communist Party members have been recruited since 2014 to stay in Uighur homes and report on any perceived “extremist” behaviors, including fasting during Ramadan. Officials have destroyed mosques, claiming the buildings were shoddily constructed and unsafe for worshippers. Uighur parents are banned from giving their babies certain names, including Mohammed and Medina. Halal food, which is prepared according to Islamic law, is becoming harder to find in Urumqi as the local government has launched a campaign against it.

Beijing has also pressured other governments to repatriate Uighurs who have fled China. In 2015, for example, Thailand returned more than one hundred Uighurs, and in 2017 Egypt deported several students. The documents released by ICIJ showed that the Chinese government instructed officials to collect information on Chinese Uighurs living abroad and called for many to be arrested as soon as they reentered China.

What has the global response been?

Much of the world has condemned China’s detention of Uighurs in Xinjiang. The UN human rights chief and other UN officials have demanded access to the camps. The European Union has called on China to respect religious freedom and change its policies in Xinjiang. And human rights organizations have urged China to immediately shut down the camps and answer questions about disappeared Uighurs.

Notably silent are many Muslim nations. Prioritizing their economic ties and strategic relationships with China, many governments have ignored the human rights abuses. In July 2019, after a group of mostly European countries—and no Muslim-majority countries—signed a letter to the UN human rights chief condemning China’s actions in Xinjiang, more than three dozen states, including Pakistan and Saudi Arabia, signed their own letter [PDF] praising China’s “remarkable achievements” in human rights and its “counterterrorism” efforts in Xinjiang. Earlier in 2019, Turkey became the only Muslim-majority country to voice concern when its foreign minister called on China to ensure “the full protection of the cultural identities of the Uighurs and other Muslims” during a UN Human Rights Council session.

In October 2019, the United States imposed visa restrictions on Chinese officials “believed to be responsible for, or complicit in” the detention of Muslims in Xinjiang, marking the toughest step by any major government to date. It also blacklisted more than two dozen Chinese companies and agencies linked to abuses in the region—including surveillance technology manufacturers and Xinjiang’s public security bureau—effectively blocking them from buying U.S. products.

Human Rights Watch has advocated other actions the United States and other countries could take: publicly challenging Xi; sanctioning senior officials, such as Chen; denying exports of technologies that facilitate abuse; and preventing China from targeting members of the Uighur diaspora. Activists have also called on the United States to grant asylum to Uighurs who have fled Xinjiang.

No comments:

Post a Comment