By Daniel DePetris

NATO is doing a relatively poor job, buttressed by a static decision-making process, a bureaucracy resistant to change, and unaccountable member states who are happy to cheap-ride and get away with it.

NATO is doing a relatively poor job, buttressed by a static decision-making process, a bureaucracy resistant to change, and unaccountable member states who are happy to cheap-ride and get away with it.

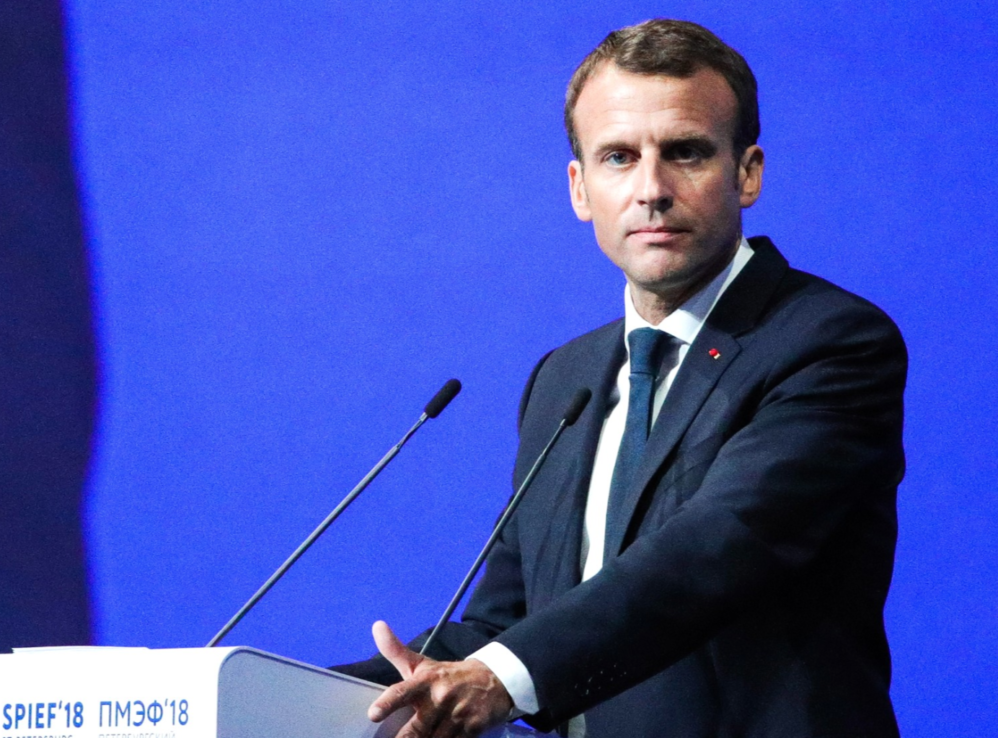

French President Emmanuel Macron is never afraid to speak his mind, as he demonstrated again sitting down with The Economist to admonish the North Atlantic Treaty Organization as a “brain dead” organization whose strategic utility desperately needs a reevaluation.

Macron lambasted the alliance for everything from disorganized planning and the lack of internal coordination to the increasing willingness of some member states, such as Turkey, to act unilaterally and in contravention to NATO principles. “[S]trategically and politically, we need to recognise that we have a problem,” Macron said.

Other NATO dignitaries quickly swatted his remarks away. NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg claimed the organization is as unified as it has ever been, and German Chancellor Angela Merkel publicly called Macron’s remarks “inappropriate.”

The Frenchman, however, is onto something. Some 30 years after the Berlin Wall crumbled, NATO is increasingly anachronistic. It is a 20th-century military organization without a foe, trying to remain relevant in a 21st-century world. The alliance is also doing a relatively poor job, buttressed by a static decision-making process, a bureaucracy resistant to change, and unaccountable member states who are happy to cheap-ride and get away with it.

NATO severely needs the very reform the foreign policy establishments on both sides of the Atlantic are programmed to resist. All 29 members should sit down and implement these reforms before the foundation of the alliance collapses. NATO, with the U.S. at the forefront, must enact these three initiatives as soon as possible.

1. NATO Should Stop Accepting New Members

First, NATO should close its doors to new members. The open-door policy, in which any country with the potential to “contribute to the security of the North Atlantic area” qualifies for NATO membership, is an albatross around the organization’s neck. Recent incorporations of Montenegro in 2017 and North Macedonia in 2019 (now in progress) have added nothing to NATO’s military capacity.

The security benefit of welcoming nations with paltry militaries and tiny defense budgets belies common sense and is far more likely to further strain the organization entirely. Given that many members outsource their defense needs to NATO, ushering more security consumers through NATO’s open door inevitably increases the risk that U.S. troops may one day be asked to participate in conflicts that have little to no effect on U.S. security or prosperity. The organization’s internal decision-making processes will only suffer; with more members included, consensus will become even more difficult to accomplish as they bring additional interests and viewpoints to the table.

Expansion into new terrain is also a recipe for further trouble and tension with Russia, a nuclear superpower that has proved itself willing to intervene militarily when it feels threatened or boxed-in. More deterioration in U.S.-Russia relations is simply not worth the policy of enlargement by auto-pilot.

2. NATO Needs Accountability

Second, NATO as an institution can use a heavy injection of accountability. Many of the problems in the alliance, one of the most significant being the massive imbalance in military capabilities between the United States and the rest of NATO, can be partly traced to an utter absence of accountability.

Internally, there are no rules ensuring proper implementation of commitments included in any number of the organization’s communiques and statements over the years. Members that flout their spending obligations (like Germany) or conduct counterproductive military operations (like Turkey) are more likely to receive a slap on the wrist than a serious reprimand.

Ideally, the North Atlantic Council would include a suspension or expulsion clause within NATO’s founding document to hold member states to their promises. But the fact that unanimity would be required for such a significant reform means that such a mechanism is highly unlikely. Individual members will therefore have to take their own initiative to drill accountability into the alliance if other members are stonewalling or violating obligations.

An unruly member wouldn’t be able to keep his or her membership at the local health club; membership in a multinational military alliance shouldn’t be any different. Systemic unaccountability, free-riding, and business-as-usual does no favors to NATO and is unfair to U.S. service members who would bear the brunt of any NATO military engagement and U.S. taxpayers who would fund it.

3. Europe Needs to Take Care of Itself

Washington should also encourage Europe’s attempts to become more autonomous in its own defense. Wealthy European states taking primary responsibility for European security directly aligns with strategically important burden-shifting, wherein security obligations are spread more evenly across the transatlantic community.

With Europe doing more to defend itself, U.S. flexibility and freedom of movement would increase, allowing more focus and resources at home and on the Asia-Pacific, an emerging center of gravity for great power competition. Greater autonomy will also shock European ministers out of their sense of complacency and prompt otherwise cautious European politicians to finally think strategically about how best to restructure Europe without remaining dependent on the United States.

Macron is right: Europe should have more control over its destiny. The United States benefits from capable partners and suffers from security dependents. Rather than serving as an obstacle, Washington should encourage this goal. Advocating for long-overdue NATO reform is a way to do it.

No comments:

Post a Comment