BY TOM O'CONNOR

The United States' decision to abandon its posts in northern Syria was not simply the result of an abrupt decision by President Donald Trump, but the product of a longer, systematic shift in the balance of power across the Middle East, where Russia and China have established new, leading roles.

The recent handover of U.S. military positions in Syria's northern city of Manbij to Russian forces, first reported by Newsweek, was a symbolic moment in this trend, a move that accompanied Syrian and Russian troops moving into a number of outposts once occupied by the Pentagon. The event occurred as Russian President Vladimir Putin made high-profile visits to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, two close U.S. partners increasingly convinced of Russia's weight in the region.

U.S. Syria Envoy Admits 'Dozens' of ISIS Fighters Have Escaped Detention

Tuesday, as a failing, five-day ceasefire brokered by Washington between Turkish-led and Kurdish-led forces neared its expiration, it was Russian President Vladimir Putin who sat down with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan in hopes of reaching a more lasting solution to his problem with Kurdish-led forces. With all the pressure of solving this decades-long conflict now primarily resting on his shoulders, however, the Russian leader still had to prove himself as a peacemaker.

"The last few days mark a new era in the politics of the Middle East," Maxim Suchkov, an expert at the Russian Council and lecturer at the Moscow State Institute of International Relations, told Newsweek.

"Russia indeed boosted its image as a new offshore balancer and the power broker in the region and acquired some opportunities on the ground in Syria which, however, are yet to be capitalized," he added.

Syrian troops wave a Russian flag at the Tabqa air base in northern Syria's Raqqa region, once the de facto capital of ISIS control, October 16. The U.S. has opted to withdraw from a battle between two partners, leaving Pentagon-supported Kurdish-led forces to side with the Russia-backed Syrian military and Turkey and its Syrian rebel allies.AFP/GETTY IMAGES

Syrian troops wave a Russian flag at the Tabqa air base in northern Syria's Raqqa region, once the de facto capital of ISIS control, October 16. The U.S. has opted to withdraw from a battle between two partners, leaving Pentagon-supported Kurdish-led forces to side with the Russia-backed Syrian military and Turkey and its Syrian rebel allies.AFP/GETTY IMAGES

The timing of Russia's fall 2015 intervention in Syria was strategic for a number of reasons. Not only did it come in time to bolster the embattled forces of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad as and allied militias, mobilized with the help of Iran, faced off with an uprising increasingly populated by jihadis, but also as the U.S. began to rethink its alliance with this Islamist-dominated opposition and partnered with the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces in order to battle the Islamic State militant group (ISIS).

Moscow had early shown skepticism toward Washington's designs in Syria, one of two countries where the so-called "Arab Spring" protests of 2011 were met with government crackdowns and quickly devolved into civil war. The first was Libya, long led by Muammar el-Qaddafi, who—like Assad—came to be denounced in the West for alleged war crimes.

Within weeks, the U.S. offered its support to a NATO coalition that enforced a no-fly-zone in support of the rebels and ultimately struck a convoy in which Qaddafi himself was riding. He was soon captured and executed by Libyan insurgents, leaving warring factions contending to head the now-leaderless country still divided by competing governments.

Russia had abstained from the United Nations Security Council resolution over Libya and, dismayed by the outcome of Qadaffi's downfall in the North African country, has sought to ensure Assad's resilience in Syria, a Soviet-era partner now hosting at least two Russian military bases along the Mediterranean. As Russian troops helped turn the tide of war, even NATO member Turkey joined pro-Assad Russia and Iran for trilateral peace talks to secure some leverage for the opposition.

Washington has boycotted these talks, largely due to its dismissal of Assad and hostility toward Tehran. While scenes of Russian forces taking over abandoned U.S. military sites in Syria and Putin's many meetings with regional leaders, including Erdogan, may symbolize a total Moscow takeover, experts say that's not exactly the case.

"Moscow doesn't have an intention to 'own' the Middle East, nor does it have the resources to do so," Suchkov told Newsweek. "Russia's strategic game plan is to construct a 'polycentric world order' where the U.S. will not be a hegemon but more non-Western states have a role to play."

"The recent developments in the Middle East speak to that goal," he added. "At a tactical level, however, Russia is in its own game and all of the moves it makes seek to bring Moscow economic investment and arms sales as well as reinforce its own positions through diplomatic mediation."

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan (L), Russian President Vladimir Putin (C) and Iranian President Hassan Rouhani (R) leave after a press conference following a trilateral meeting on Syria, in Ankara on September 16. Putin has so far managed to bridge Erdogan and Rouhani's opposing goals in Syria.ADEM ALTAN/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan (L), Russian President Vladimir Putin (C) and Iranian President Hassan Rouhani (R) leave after a press conference following a trilateral meeting on Syria, in Ankara on September 16. Putin has so far managed to bridge Erdogan and Rouhani's opposing goals in Syria.ADEM ALTAN/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

Samuel Ramani, a doctoral candidate at Oxford University, agreed. He told Newsweek that "there is a common misconception that Russia is trying to replace the United States," but, in fact, "Russia's not trying to be the security guarantor."

"What you're seeing is an increasingly tripolar system in the Middle East—the U.S as a security guarantor, China emerging as a major economic powerhouse in the region and Russia as the only actor that can play a role in de-escalating tensions," Ramani explained. "Russia is not trying to be equal with China economically and it doesn't have the staying power to rival the United States, so it's carving out a sort of niche in crisis diplomacy."

Since the onset of its entrance into Syria's conflict on behalf of Damascus, Moscow has kept open contacts with just about every major player. This includes Iran, which was already backing Assad, as well as the Islamic Republic's two top regional foes, Israel and Saudi Arabia, both of whom backed the opposition.

The Astana process that brought Turkey and Iran together only cemented Russia's central position, gathering representatives of the government and opposition. While the Syrian Democratic Forces have been excluded from U.N.-backed talks to establish a new Syrian constitution, Moscow has separately maintained relations with Kurdish forces and has since proven a vital asset in facilitating their talks with Damascus.

"It's the only country that can talk to everyone, it's been doing that with Israel and Iran, the YPG and the Syrian army, it's actually getting people in the room together," Ramani said, noting that Russia has also "been finding common ground between Saudi Arabia and Iran" and may expand its role in the crises affecting Libya and Yemen.

The Sunni Muslim monarchies of the Arabian Peninsula have long been close partners of U.S. foreign policy and readily embraced Trump's anti-Iran rhetoric. As attacks on oil tankers and strikes on Saudi oil facilities appeared to raise the risk of conflict in the Persian Gulf region, however, Ramani explained how Moscow came to be seen as the potential preferred arbiter.

"Russia is very actively investing in soft power and appealing to Arab leaders and publics as well," Ramani told Newsweek. "Russia is not intervening in the internal affairs of these countries in terms of human rights and authoritarianism. It cares more about state civility than the nature of their state, they don't meddle in their internal affairs."

As Moscow pushes for the Arab League to reverse its 2011 suspension of Syria over alleged human rights abuses, Ramani said that Russia is engaging Arab countries on Syria as a hedge against Iran and Turkey," two non-Arab states gaining ground in the war-torn country.

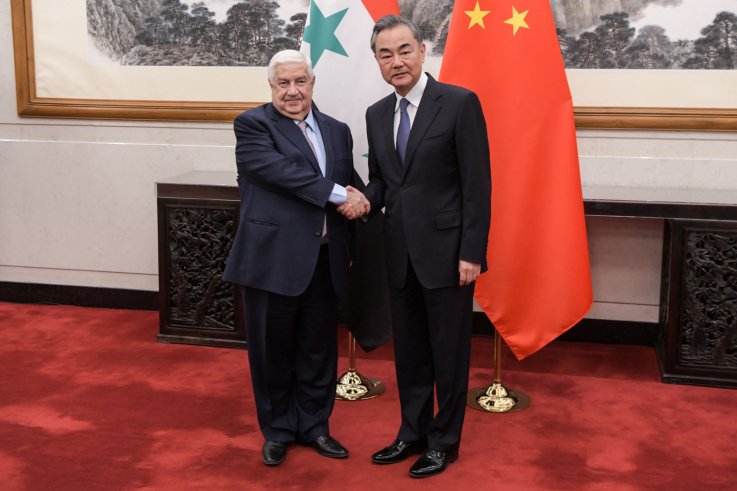

Syrian Foreign Minister Walid al-Muallem (L) poses for a picture with Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi during a meeting at Diaoyutai state guesthouse in Beijing, June 18. China has backed Syrian President Bashar al-Assad politically and, to some extent, economically in his war against rebels and jihadis.FRED DUFOUR/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

Syrian Foreign Minister Walid al-Muallem (L) poses for a picture with Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi during a meeting at Diaoyutai state guesthouse in Beijing, June 18. China has backed Syrian President Bashar al-Assad politically and, to some extent, economically in his war against rebels and jihadis.FRED DUFOUR/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

Meanwhile, China has played the role of a far more silent partner in the evolution of the region's international dynamics. The Middle East, a crossroads of Asia, Africa and Europe, has been envisioned as a crucial node in Chinese President Xi Jinping's Belt and Road Initiative, through which he has sought to establish a cross-continental network of infrastructure projects.

Syria's reconstruction may prove to be a major opportunity to expand Chinese capital across the Middle East and, in addition to hosting Russian military facilities, the Syrian ports of Tartous and Latakia may soon see major Chinese investment. Beijing has additionally eyed buying into the Lebanese port of Tripoli and has already established a financial presence at Israel's Haifa port farther south on the Mediterranean.

The official online portal for the global plan names some 138 countries that have entered into some form of cooperation with China's Belt and Road Initiative. The U.S. views it as a major threat to its own economic dominance, especially at a time when Beijing and Washington have been engaged in a global trade war of tit-for-tat tariffs.

China has also managed to court Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates with multibillion-dollar deals, even as it remained rival Iran's top trading partner in defiance of U.S. sanctions. Beijing has also welcomed Moscow's call for a regional security framework similar to Tehran's "Coalition for Hope," or Hormuz Peace Endeavor, designed to bring together Iran and Arab neighbors and ensure stability in and around the world's important chokepoint for maritime oil traffic, and a lifeline for China.

Loading...

Adding to their separate rises on the world stage, Russia and China have more often sought cooperation over competition, at least at this stage of their ties—considered by both to be "the best in history." While the status of reported upcoming joint Russian-Chinese-Iranian naval drills in the Indian Ocean remained unclear, Beijing has benefited from an unprecedented pace of joint exercises with Moscow, which was seeking to enhance its economic clout with the Eurasian Economic Union, whose newest member was none other than Iran.

After nearly two decades of lengthy, open-ended conflict in the Middle East, Trump has sought to embody U.S. fatigue over these so-called "endless wars." In defending his decision to withdraw from Syria, the U.S. leader suggested last week that either "Russia, China, or Napoleon Bonaparte" assist Syria in backing Kurdish-led forces against Turkey, but—the long-dead French leader aside—it remained to be seen whether the two emerging powers could succeed where the U.S. chose to walk away.

No comments:

Post a Comment