The U.S. seems to be nearing a withdrawal from Afghanistan. After nearly a year of talks, U.S. and Taliban negotiators have in hand a draft agreement for a peace deal to end the 18-year war. The Trump administration, which has long wanted to withdraw forces from the country, still wants to maintain some combat capability there. Reports over the weekend indicate that administration officials have suggested expanding the CIA’s presence in Afghanistan, but Langley is resisting an increased role for the agency there. The CIA, technically speaking, does not represent combat capability. But practically, it could serve as a liaison to factions opposed to the Taliban, providing tactical information for airstrikes and carrying out a range of strategic actions. This suggests that whatever withdrawal the U.S. is considering is a political one.

The U.S. seems to be nearing a withdrawal from Afghanistan. After nearly a year of talks, U.S. and Taliban negotiators have in hand a draft agreement for a peace deal to end the 18-year war. The Trump administration, which has long wanted to withdraw forces from the country, still wants to maintain some combat capability there. Reports over the weekend indicate that administration officials have suggested expanding the CIA’s presence in Afghanistan, but Langley is resisting an increased role for the agency there. The CIA, technically speaking, does not represent combat capability. But practically, it could serve as a liaison to factions opposed to the Taliban, providing tactical information for airstrikes and carrying out a range of strategic actions. This suggests that whatever withdrawal the U.S. is considering is a political one.

The U.S. main force will be withdrawn, but the U.S. will still know what’s going on tactically and will retain the ability to launch selective strikes. Uniformed troops will be replaced by ununiformed officials. This is, of course, certainly not the first time the U.S. has used CIA and special operations forces in collaboration with local forces to manage the situation in a country; the U.S. withdrew from Somalia and Lebanon but retained capabilities there. If we’re to learn anything from those instances, it’s that the level of violence will decline, but there will still be deaths, just with far less publicity.

Before the War

In all of this, we need to recall why the United States went into Afghanistan in the first place. On Sept. 10, 2001, the last thing anyone thought would ever happen was a U.S. invasion of Afghanistan. The United States had backed the mujahideen’s insurgency after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, and understood the terrain, the tribal rivalries and the difficulty of operating in that environment. The insurgency turned what the Soviets had expected would be an operation of surgical precision into a decadelong morass. The U.S. may very well have had to go into Afghanistan, but it had no right to be surprised at what happened next.

As the Soviets withdrew from Afghanistan, a complex civil war broke out in which, essentially, the Northern Alliance waged a war of resistance against the rising Taliban. Pakistan, which has long had a major interest in its northwestern neighbor, got involved; its intelligence service factored into the Taliban’s victory in the civil war. And as the Taliban, led by Mullah Mohammed Omar, deepened its control, it gave sanctuary to al-Qaida.

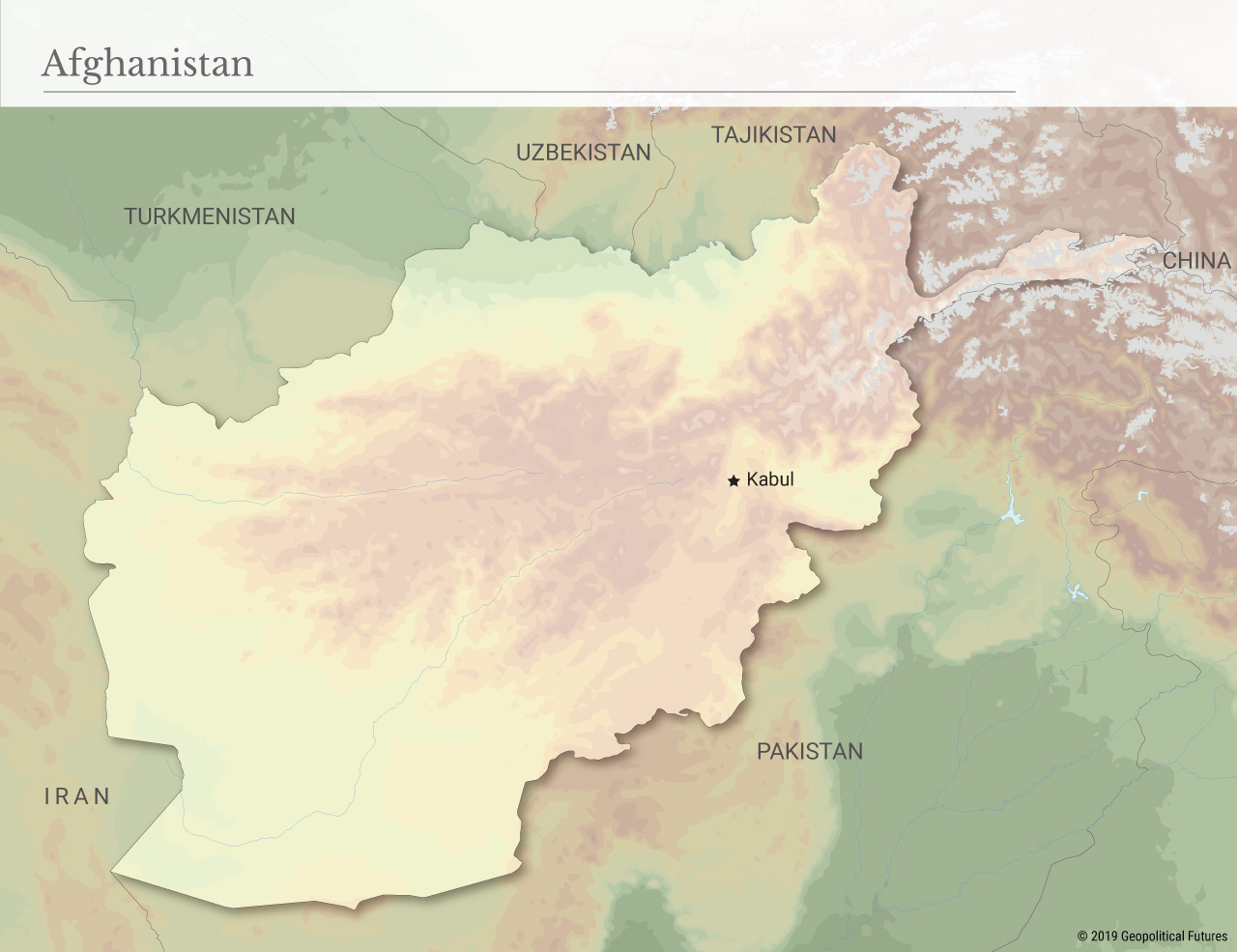

Still, the United States did not see Afghanistan as being of strategic interest. The Americans had come to see Afghanistan not as a prize but as a swamp. Any of its neighbors – from Iran and Pakistan to Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan and even China – could chew off a piece, but trying to conquer the whole would simply bog you down permanently. Each of these countries’ intelligence services might probe here and there, and deals could be made, but nobody could possibly conquer and occupy the entire country. Even the Taliban at the height of its power could not control it all. From the American point of view, anyone who wanted to replicate the Soviet disaster was welcome to do so.

Into the Morass

What U.S. intelligence had missed was not al-Qaida; the U.S. undoubtedly knew its base was in Afghanistan. What it failed to understand was that al-Qaida had a cadre of operatives able to penetrate the U.S., maintain contact with al-Qaida, receive funding and obtain pilot training. That cadre went undetected right up until they executed a spate of planned, simultaneous hijackings and suicide attacks.

The problem for the U.S. was that its intelligence agencies clearly had no idea what else al-Qaida could do, given that the intelligence community did not detect the 9/11 plot. The only way the U.S. saw to disrupt al-Qaida operations was to attack the organization in Afghanistan. Since a full-scale invasion could not be launched in the timeframe imagined, it was the CIA, with its excellent contacts in Afghanistan, that purchased alliances with various groups and, supported by a fairly small force of Marines, conducted the main attack. Osama bin Laden, aware of the force being marshaled, escaped into Pakistan. Al-Qaida command was disrupted but not destroyed.

This was the critical point. Having sent in troops and reinforcements, the U.S. had no clear strategy for Afghanistan. The country was of interest only to the extent that al-Qaida operated from there. The concern, then, became that al-Qaida might return. The CIA, rather than the U.S. military, used its contacts and funds to build up a local force against al-Qaida. To some extent, that narrow operation was a success. But the attempt to occupy Afghanistan made almost no sense. In essence, the U.S. was willingly putting itself in the same position as the Soviets – who had failed.

The fear that al-Qaida would return to Afghanistan was understandable. But al-Qaida was mobile and had a flexible command structure. It didn’t require some massive control center, even for 9/11. To destroy al-Qaida would mean widespread warfare. But the U.S. did not have to occupy countries. As I have argued elsewhere, occupation warfare is the most difficult form of war; even the Nazis, with no limits on brutality, could never defeat Tito’s guerillas.

The defeat of a group like al-Qaida depended on intelligence and special operations forces. The group was built for dispersal because of its sparseness, and at any given time it could operate globally; the occupation of any one country could not destroy al-Qaida. Perhaps the core problem the U.S. had in Afghanistan was not that it forgot the lessons of the Soviet war but that it used the term “invasion” to describe how it dislodged al-Qaida. The U.S. did not disperse al-Qaida; it launched a covert operation that used money to motivate local forces familiar to the United States, backed by U.S. air power. The actual invasion was an attempt to turn sanctuary denial for a terrorist group into a conventional war.

It didn’t work. The U.S. had minimal interest in Afghanistan beyond al-Qaida, and al-Qaida was everywhere and nowhere. The U.S. could not impose its will on Afghanistan no matter how many divisions it brought in. But it was a passionate time in the U.S., and reasonably so. It was also an example of the dangers of passion.

So now we are back to where we began. The military will leave, and the CIA will take over with far more modest goals. The CIA is not going to try to engage in nation-building; rather it will try to maintain the flow of intelligence and carry out covert operations with special operations forces to keep the enemy off balance. As it was in the beginning, so it shall now be again. And, of course, the CIA is resisting. There will be no glory in winning – there is no winning in Afghanistan, only perpetual engagement. But without winning as an option, a much smaller investment is needed.

No comments:

Post a Comment