Zak Doffman

The FBI has warned that “the threat” to U.S. election security “from nation-state actors remains a persistent concern,” that it is “working aggressively” to uncover and stop, and the U.S. Director of National Intelligence has appointed an election threats executive, explaining that election security is now “a top priority for the intelligence community—which must bring the strongest level of support to this critical issue.”

The FBI has warned that “the threat” to U.S. election security “from nation-state actors remains a persistent concern,” that it is “working aggressively” to uncover and stop, and the U.S. Director of National Intelligence has appointed an election threats executive, explaining that election security is now “a top priority for the intelligence community—which must bring the strongest level of support to this critical issue.”

With this in mind, a new report from cybersecurity powerhouse Check Point makes for sobering reading. “It is unequivocally clear to us,” the firm warns, “that the Russians invested a significant amount of money and effort in the first half of this year to build large-scale espionage capabilities. Given the timing, the unique operational security design, and sheer volume of resource investment seen, Check Point believes we may see such an attack carried out near the 2020 U.S. Elections.”

None of which is new—it would be more surprising if there wasn’t an attack of some sort, to some level. What is new, though, is Check Point’s unveiling of the sheer scale of Russia’s cyberattack machine, the way it is organised, the staggering investment required. And the most chilling finding is that Russia has built its ecosystem to ensure resilience, with cost no object. It has formed a fire-walled structure designed to attack in waves. Check Point believes this has been a decade or more in the making and now makes concerted Russian attacks on the U.S. “almost impossible” to defend against.

Today In: Innovation

The new research was conducted by Check Point in conjunction with Intezer—a specialist in Genetic Malware Analysis. It was led by Itay Cohen and Omri Ben Bassat, and has taken a deep dive to get “a broader perspective” of Russia’s threat ecosystem. “The fog behind these complicated operations made us realize that while we know a lot about single actors,” the team explains, “we are short of seeing a whole ecosystem.”

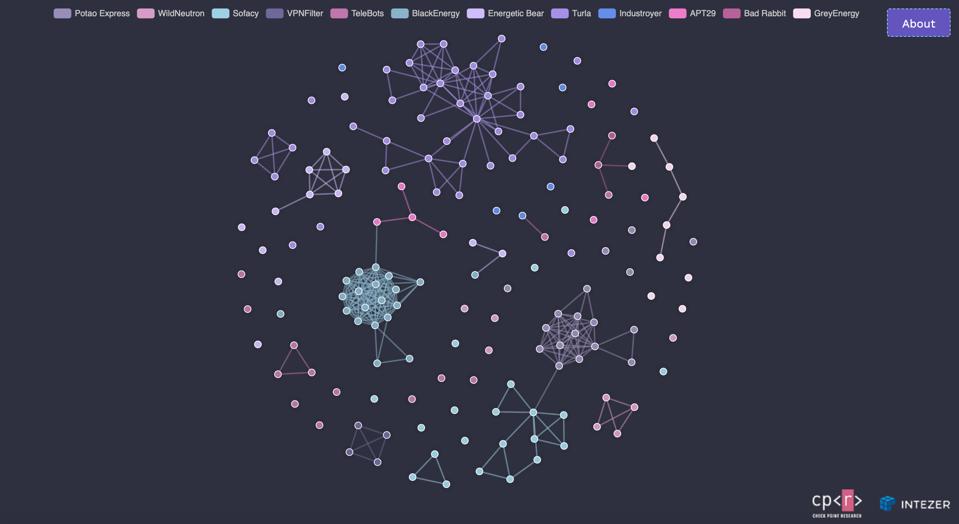

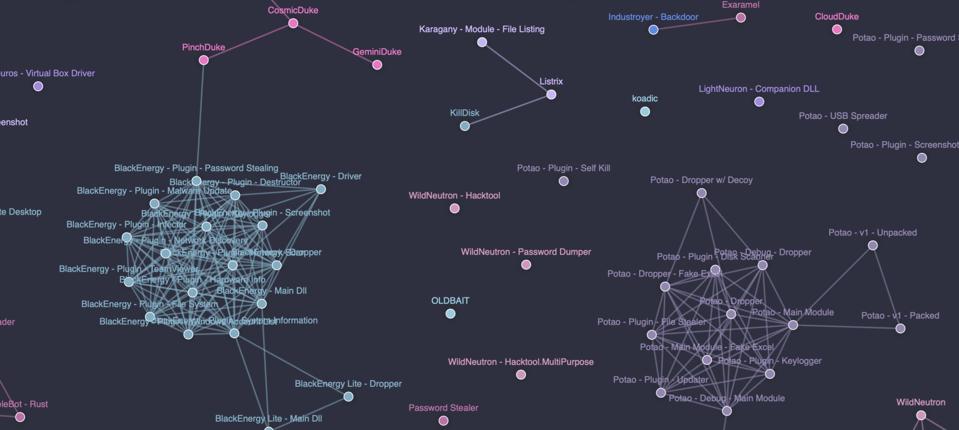

And the answer, Check Point concluded, was to analyse all the known data on threat actors, attacks and malware to mine for patterns and draw out all the connections. “This research is the first and the most comprehensive of its kind—thousands of samples were gathered, classified and analyzed in order to map connections between different cyber espionage organizations of a superpower country.”

PROMOTED

The team expected to find deep seated linkages, connections between groups working into different Russia agencies—FSO, SVR, FSB, GRU. After all, one can reasonably expect all of the various threat groups sponsored by the Russian state to be on the same side, peddling broadly the same agenda.

But that isn’t what they found. And the results from the research actually carry far more terrifying implications for Russia’s capacity to attack the U.S. and its allies on a wide range of fronts than the team expected. It transpires that Russia’s secret weapon is an organisational structure which has taken years to build and makes detection and interception as difficult as possible.

“The results of the research was surprising,” Cohen explains as we talk through the research. “We expected to see some knowledge, some libraries of code shared between the different organizations inside the Russian ecosystem. But we did not. We found clusters of groups sharing code with each other, but no evidence of code sharing between different clusters.” And while such findings could be politics and inter-agency competition, the Check Point team have concluded that it’s more likely to have an operational security motive. “Sharing code is risky—if a security researcher finds one malware family, if it has code shared with different organizations, the security vendor can take down another organisation.”

The approach points to extraordinary levels of investment. “From my perspective,” Yaniv Balmas, Check Point’s head of cyber research tells me. “We were surprised and unhappy—we wanted to find new relationships and we couldn't. This amount of effort and resources across six huge clusters means huge investment by Russia in offensive cyberspace. I have never seen evidence of that before.”

And the approach has been some time in the making. “It’s is an ongoing operation,” Cohen says, “it’s been there for at least a decade. This magnitude could only be done by China, Russia, the U.S. But I haven't seen anything like it before.”

The research has been captured in “a very nice map,” as Balmas described it. This map has been built by Check Point and Israeli analytics company Intezer, a complex interactive tool that enables researchers to drill down into malware samples and attack incidents, viewing the relationships within clusters and the isolated firewalls operating at a higher level.

CHECK POINT

The research has been angled as an advisory ahead of the 2020 U.S. elections. Russia has the capability to mount waves of concerted attacks. It’s known and accepted within the U.S. security community that the elections will almost certainly come under some level of attack. But the findings actually point to something much more sinister. A cyber warfare platform that does carry implications for the election—but also for power grids, transportation networks, financial services.

CHECK POINT

“That’s the alarming part,” Check Point’s Ekram Ahmed tells me. “The absence of relationships. The sheer volume and resource requirements leads us to speculate that it’s leading up to something big. We’re researchers— if it’s alarming to us, it should definitely be alarming to the rest of the world.”

So what’s the issue? Simply put, it’s Russia’s ability to attack from different angles in a concerted fashion. Wave upon wave of attack, different methodologies with a common objective. And finding and pulling one thread doesn’t lead to any other cluster. No efficiencies have been sought between families of threat actors. “Offense always has an advantage over defense,” Balmas says, “but here it’s even worse. Given the resources Russia is putting in, it’s practically impossible to defend against.”

“It’s alarming,” Check Point explains in its report, “because the segregated architecture uniquely enables the Russians to separate responsibilities and large-scale attack campaigns, ultimately building multi-tiered offensive capabilities that are specifically required to handle a large-scale election hack. And we know that these capabilities cost billions of dollars to build-out.”

I spend lot of time talking to cybersecurity researchers—it’s a noisy space. And given current geopolitics, the Gulf, the trade war, the “splinternet,” there is plenty to write about. But I get the sense here that there’s genuine surprise and alarm at just what has been seen, the extent and strategic foresight that has gone into it, the implications.

And one of those implications is that new threats, new threat actors if following the same approach will be harder to detect. The Check Point team certainly think so. “This is the first time at such a scale we have mapped a whole ecosystem,” the team says, “the most comprehensive depiction yet of Russian cyber espionage.”

And attacks from Russia, whichever cluster might be responsible, tend to bear different hallmarks to the Chinese—or the Iranians or the North Koreans.

“Russian attacks tend to be very aggressive,” Balmas explains. “Usually in offensive cyber and intelligence, the idea is to do things that no-one knows you're doing. But the Russians do the opposite. They’re very noisy. Encrypting or shutting down entire systems they attack. Formatting hard drives. They seem to like it—so an election attack would likely be very aggressive.”

With 2020 in mind, Ahmed explains, “given what we can see, the organization and sheer magnitude of investment, an offensive would be difficult to stop—very difficult.”

Cohen reiterates the staggering investment implications of what they’ve found. “This separation shows Russia is not afraid to invest enormous amount of money in this operation. There’s no effort to save money. Different organisations with different teams working on the same kind of malware but not sharing code. So expensive.”

All the research and the interactive map is available and open source, Cohen explains, “researchers can see the connections between families, better understanding of evolution of families and malware from 1996 to 2019.”

The perceived threat to the 2020 election is “speculation,” Check Point acknowledges. “But it’s based on how the Russians are organizing, the way they're building the foundation of their cyber espionage ecosystem.”

So, stepping back from the detail what’s the learning here? There have been continual disclosures in recent months on state-sponsored threat actors and their tactics, techniques and procedures. The last Check Point research I reported on disclosed China’s trapping of NSA malware on “honeypot” machines. Taken in the round, all of this increased visibility on Russian and Chinese approaches, in particular, provides a better sense of the threats as the global cyber warfare landscape becomes more complex and integrated with the physical threats we also face.

On Monday [September 23], 27 nation-states signed a “Joint Statement on Advancing Responsible State Behavior in Cyberspace,” citing the use of cyberspace “to target critical infrastructure and our citizens, undermine democracies and international institutions and organizations, and undercut fair competition in our global economy by stealing ideas when they cannot create them.”

The statement was made with Russia and China in mind, and a good working example of how such attack campaigns are supported in practice can be viewed by exploring Check Point’s Russian cyber espionage map, which is now available online.

No comments:

Post a Comment