Emile Dirks

Introduction

The repression of Xinjiang’s Uighur population by the government of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) continues to horrify world opinion. Along with interning an estimated one million people in a network of re-education camps, the Chinese state has built extensive systems of daily surveillance directed at the region’s Muslims (China Brief, March 14, 2017; China Brief, November 5, 2018). [1] Police inspections of local homes, blacklists of suspect Muslims, and biometric data collection are widespread.

Previous research has illustrated how such policies have their roots in earlier (and ongoing) repression campaigns against Falun Gong and other religious groups (China Brief, February 1). However, evidence now suggests that these systems of social surveillance and repression also originated in programs directed at wider groups of Chinese citizens, identified as “key individuals” (重点人员, zhongdian renyuan). Systems of “key population management” (重点人口管理, zhongdian renkou guanli) possess many of the features associated with Xinjiang’s security state: profiling, extensive personal and biometric data collection, and location-based tracking.

Drawing on dozens of local government notices, government bid tenders and promotional material from Chinese technology companies, a composite picture of key population management can be assembled. By examining key individuals management, we can learn more about the roots of the PRC’s anti-Muslim surveillance programs—programs that one day may be directed against ever-increasing new segments of the Chinese public.

Who Are “Key Individuals”?

Although “key individuals” are a topic of frequent discussion in mainland Chinese academic literature, the concept has been little discussed outside China. [2] The term therefore requires some explanation. According to the 2007 Key Population Management Guidelines (公安部重点人口管理规定, Gongan Bu Zhongdian Renkou Guanli Guiding) issued by the PRC Ministry of Public Security (hereafter “Guidelines”), key individuals are persons suspected of threatening national security or social stability (Junan County Government, October 18, 2017). Article 3 of the Guidelines associates 20 kinds of people into two broadly defined general categories: potential national security threats and serious criminal offenders. Article 4 specifies three other groupings as key individuals: individuals involved in disputes with the potential for dangerous escalation; people released from prison or re-education through labor camps; and users of illegal drugs.

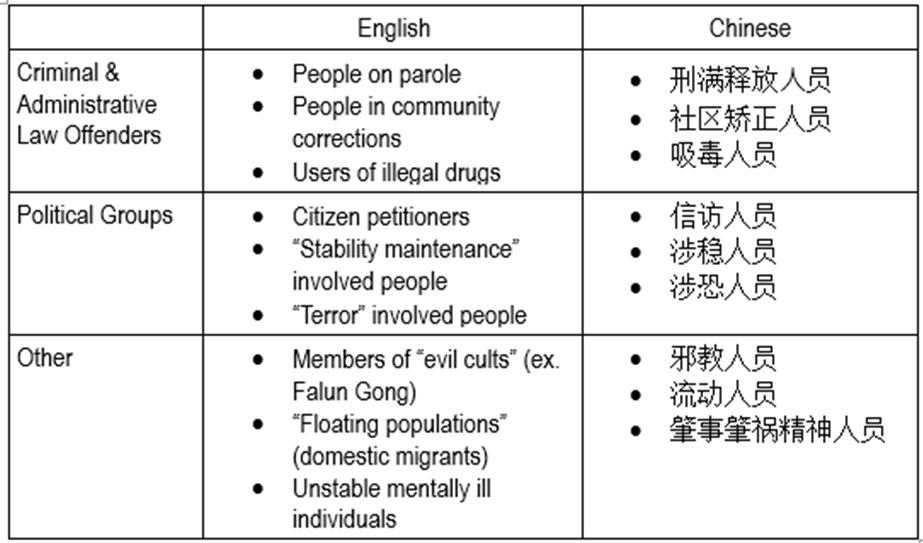

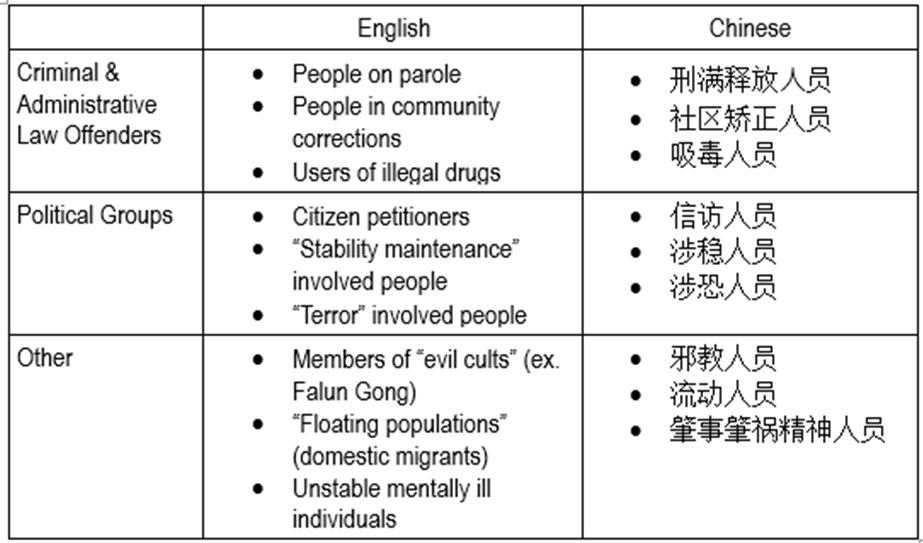

While the Guidelines establish the general parameters of whom key individuals are, local government notices indicate which groups are routinely placed under surveillance. Examining more than 70 online notices from 26 of China’s 34 administrative regions published between 2011 and 2019 reveals the following most frequently mentioned key individual groups: [3] Image: Categories of Key Individuals Mentioned in Local Government Notices. (Source: Author’s Notes.)

Image: Categories of Key Individuals Mentioned in Local Government Notices. (Source: Author’s Notes.)

Image: Categories of Key Individuals Mentioned in Local Government Notices. (Source: Author’s Notes.)

Image: Categories of Key Individuals Mentioned in Local Government Notices. (Source: Author’s Notes.)

From these notices, we can see that local authorities interpret key individuals categories broadly: for example, domestic migrants, citizen petitioners, and the mentally ill are not specifically mentioned in the Guidelines, but they are frequently discussed in local government notices.

Data Collection and Databases in Key Individuals Management

Regardless of which groups are targeted, data collection lies at the heart of key individuals management. Government notices routinely instruct local officials and public security officers to work in concert to collect information on key individuals, a process referred to as “investigating” (排查, paicha) or “assessing and investigating” (摸底排查, modi paicha) (Tianjin Baodi Government, December 12, 2018). As data collection efforts have grown, so too has the need for specialized police-run key individuals databases.

A core feature of the PRC’s campaign against Uighurs has been the creation of vast police databases of information on Uighur citizens (Human Rights Watch, May 1). Disturbing as these databases are, their origins predate the current anti-Muslim campaigns and extend back to the mid-2000s, with the introduction of machine-readable national ID cards (Keesing Journal of Documents & Identity, 2010). These so-called “second generation” ID cards (第二代身份证, di er dai shenfenzheng) allowed personal data to be stored electronically and shared among government offices, including the Public Security Bureau. It was then that the Chinese government first began collaborating with domestic tech firms to create digital databases of key individuals—including religious minorities.

One of the first nation-wide key individuals databases was the “Drug User Online Dynamic Control Alert System” (吸毒人员网上动态管控预警系统, Xidu Renyuan Wangshang Dongtai Guankong Yujing Xitong) (PRC Ministry of Public Security, August 29, 2006). Launched in 2006 as part of China’s “People’s War on Drugs” (人民禁毒战争, Renmin Jindu Zhanzheng), the Dynamic Control System (DCS) contains personal information on more than two million registered users of illegal drugs, including those held in or released from extrajudicial drug detention centers. Government reports, media coverage and academic scholarship give a sense of what data are collected in the DCS: basic personal information, residential address, and history of drug use and participation in drug treatment programs. [4]

The DCS is also one of the earliest examples of ID-based location tracking and biometric data collection aimed at key individuals—predating the collection of DNA samples from Uighurs by a decade. Whenever a registered user of drugs uses their national ID number to conduct a computer-based transaction (such as checking in to a hotel room), the nearest public security offices are alerted. Police officers can then identify the person’s location, intercept them, and conduct a urine drug test, the results of which can be added to the person’s file (International Drug Policy Consortium, February 2017).

Biometric data collection is not limited to urine drug test results. Article 6 of the 2008 “Drug User Registration Methods” (吸毒人员登记办法, Xidu Renyuan Dengji Banfa) refers to collecting fingerprints and DNA data on individuals whose identities police cannot verify (Legal Daily, September 24, 2009). As early as November 2017, reports from Hainan indicated that police had begun collecting DNA samples from registered drug users as part of regular key individuals management operations (Hainan Daily, November 25, 2007).

Chinese Tech Firms as Contractors for the PRC’s Domestic Surveillance System

The DCS quickly became a template for other key individuals databases—and Chinese tech firms have become extensively engaged as contractors working to support these government programs. Absent a purchased copy, direct examination of this software is impossible. One exception is Hongda (宏达) Software’s “Public Security Personnel Information Management Work System” (公安人员信息管理工作系统, Gongan Renyuan Xinxi Guanli Gongzuo Xitong), released in 2008. [5] The software’s user help document—complete with extensive screenshots of the system’s interface—is freely available for download and provides a clear insight into how the software allows police to monitor a range of key individuals, including former prisoners, users of drugs, and foreigners.

One of the key individuals categories listed in Hongda’s system are “practitioners of evil cults” (邪教人员, xiejiao renyuan). The PRC government launched a campaign of imprisonment, intimidation, and torture against members of the Falun Gong spiritual movement in 1999, and the Hongda example illustrates that by 2008 (a period when surveilling Falun Gong adherents was a priority for local public security organs in the lead up to the Beijing Olympics) the Chinese government was already working with domestic tech companies to monitor religious minorities. To this end, the Management Work System permitted police to catalogue known practitioners according to precise criteria: who introduced them to the movement; where and with whom they practiced; and their “level of [spiritual] obsession” (痴迷程度, chimi chengdu). Such rankings now read as disturbing precursors to the police assessments of Uighurs as “safe”, “average”, and “unsafe” (The Guardian, April 11).

Since the release of Hongda’s Information Management System, police interest in key individuals databases has only grown. Key word searches on China Bidding (中国采购与招标网, Zhongguo Caigou yu Zhaobiao Wang) and Bid Center (采招网, Cai Zhao Wang) turned up twenty two public tenders for key individuals databases or related surveillance products, issued by local government offices in 15 different provinces or centrally administered cities between October 2015 and June 2019. [6]

China’s tech companies have responded to these business opportunities. In addition to Hongda Management Software, a cursory online search revealed five other firms offering key individuals-related software for public security organs:

Shenzhen Yuanzhongrui Technology (深圳源中瑞科技)

Beijing Sensingtech LLC (北京深醒科技有限公司)

Zhejiang Yidiantong Information Technology Ltd. (浙江亿点通信息科技有限公司)

CASIC Guangda Technology Ltd. (北京航天光达科技有限公司)

Shenzhen Harzone Technology Ltd. (深圳市华尊科技有限公司)

The website for Yidiantong Information Technology’s “Key Individuals Control” (重点人员管控, Zhongdian Renyuan Guankong) (KIC) provides the most detailed overview of one of these systems (Zhejiang Yidiantong ‘Product Page,’ undated). [7] Like other key individuals databases, Key Individuals Control can record extensive personal information on registered persons, including social media accounts and bank account details. And like the DCS, KIC is integrated with the information systems of hotels, internet cafes, airports, and railway stations to enable both real-time data sharing and targeted police actions against registered individuals.

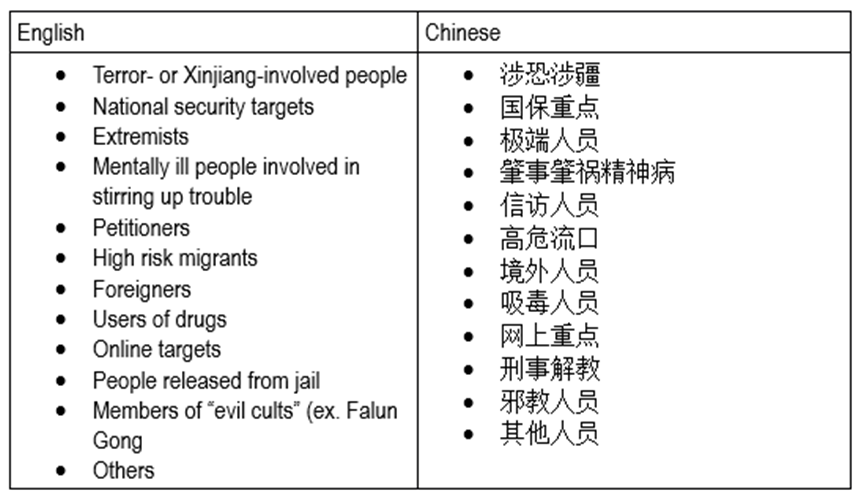

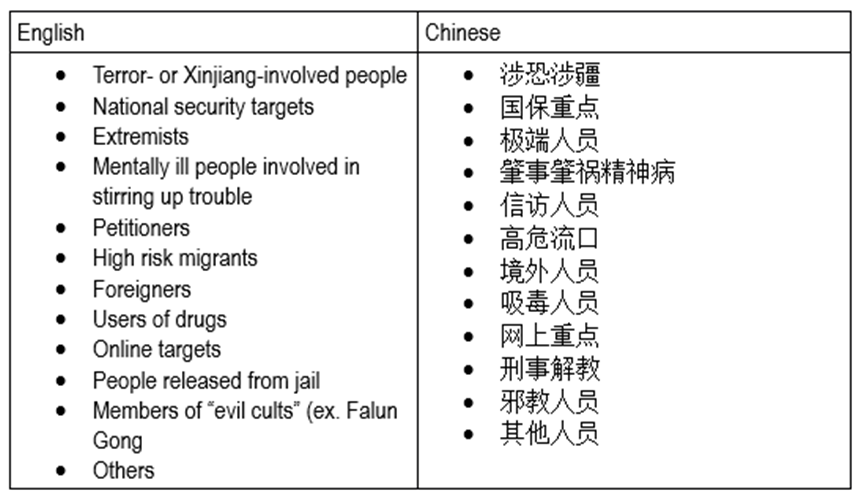

Yidiantong’s website also indicates that the range of key individuals groups has continued to expand: Image: Key Categories of People Mentioned in Yidiantong’s Key Individuals (Source: Author’s Notes.)

Image: Key Categories of People Mentioned in Yidiantong’s Key Individuals (Source: Author’s Notes.)

Image: Key Categories of People Mentioned in Yidiantong’s Key Individuals (Source: Author’s Notes.)

Image: Key Categories of People Mentioned in Yidiantong’s Key Individuals (Source: Author’s Notes.)

That people from Xinjiang, petitioners, migrants, the mentally ill, foreigners, and online targets do not appear in the 2007 Guidelines suggests that tech companies are building databases in response to extralegal demands from public security agencies, rather than public policy documents or statutory law.

As the market for key individuals databases increases, so too has the range of related products, including China’s often-discussed facial recognition cameras. However, as this research suggests, it is police officers and low-level bureaucrats—armed with computers, clipboards, and handheld data entry devices—who continue to be the most reliable eyes of the PRC’s growing state apparatus for methodically enumerating China’s most marginalized members of society. For this reason, one of the most unsettling aspects of Yidiantong’s Key Individuals Control system is its related “Community Alert” (社区警务, Shequ Jingwu) program. [8] By using Community Alert, police can create simple two-dimensional maps of apartment complexes, and associate particular key individuals—whether petitioners, foreigners, users of drugs, “cult” members, or the mentally ill—with specific apartment units. Such maps further facilitate the forms of intrusive surveillance, unannounced interrogations, and biometric data collection detailed in local government notices.

Conclusion

Key individuals management and data collection did not begin in Xinjiang, nor is it likely to end there. Software programs first deployed against users of drugs in the mid-2000s were soon directed against members of Falun Gong. By the late 2010s, the net had widened to ensnare the Uighurs of Xinjiang. Now these tools of data collection and surveillance, refined in Kashgar and Urumqi, are being redeployed across the rest of China. It is unclear what key individuals these systems will target next. What is clear is that in the absence of robust media or judicial oversight—or any other institutional checks on the Communist Party’s domestic security apparatus—key individuals management will continue to metastasize, bringing ever greater swaths of the Chinese public under its control.

Emile Dirks is an independent researcher based in Toronto, Canada whose work focuses on extrajudicial detention and government surveillance in the People’s Republic of China.

No comments:

Post a Comment