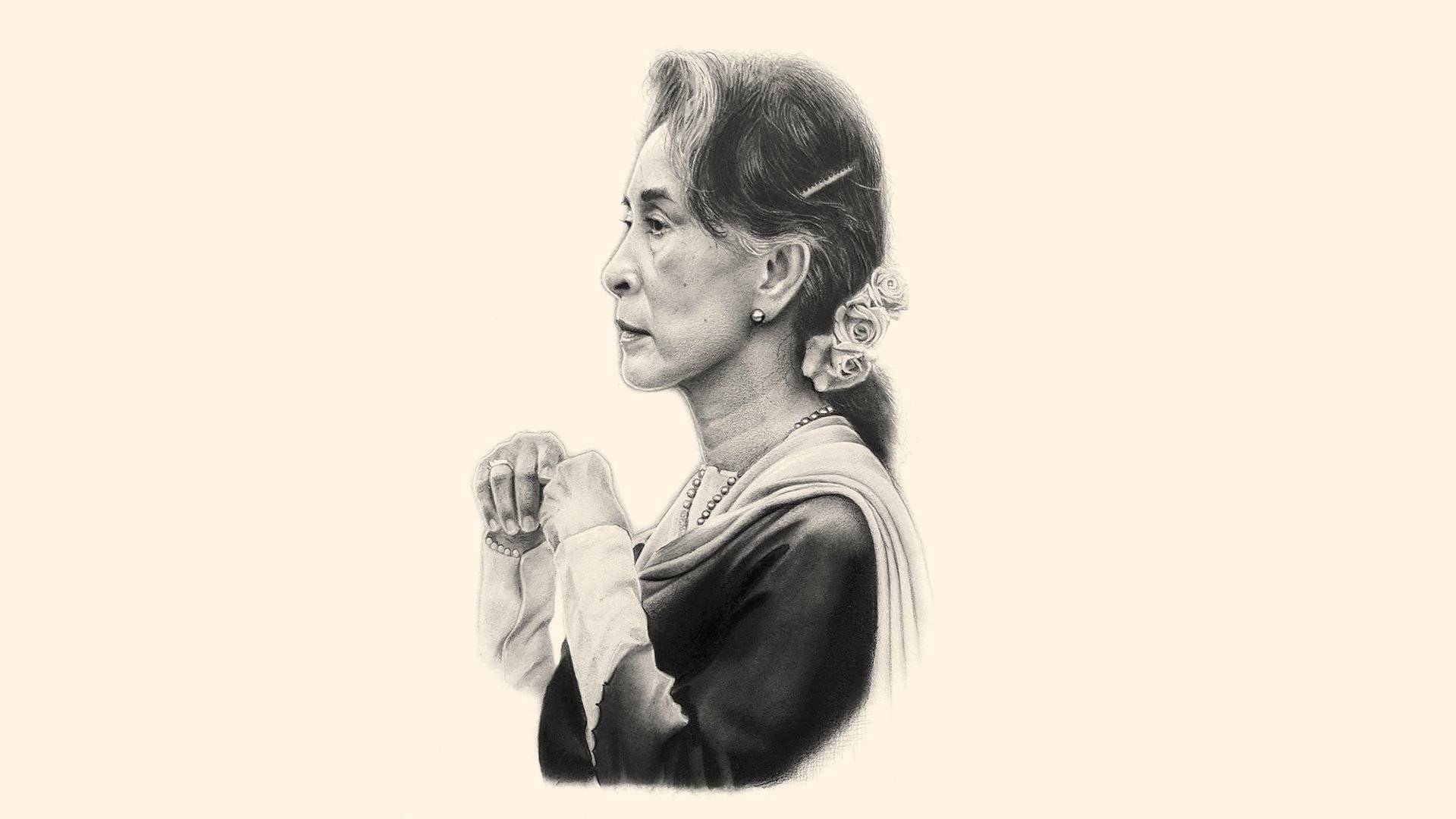

The first time I met Aung San Suu Kyi, she embodied hope. It was November 2012, and we were in her weathered house at 54 University Avenue, in Yangon, where she’d been held prisoner by the ruling Burmese junta for the better part of two decades. She sat at a small, round table with Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton, and Derek Mitchell, who had recently been named the first U.S. ambassador to Myanmar in more than 20 years. At 67, Suu Kyi was poised and striking, a flower tucked into her long black hair, which was streaked with gray. Looking up at the worn books on the shelves behind her, I imagined the hours she must have spent reading them in enforced solitude. A picture of Mahatma Gandhi looked down with a serene smile.

The first time I met Aung San Suu Kyi, she embodied hope. It was November 2012, and we were in her weathered house at 54 University Avenue, in Yangon, where she’d been held prisoner by the ruling Burmese junta for the better part of two decades. She sat at a small, round table with Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton, and Derek Mitchell, who had recently been named the first U.S. ambassador to Myanmar in more than 20 years. At 67, Suu Kyi was poised and striking, a flower tucked into her long black hair, which was streaked with gray. Looking up at the worn books on the shelves behind her, I imagined the hours she must have spent reading them in enforced solitude. A picture of Mahatma Gandhi looked down with a serene smile.

The meeting was a high-water mark for three historic figures. Obama had just decisively won a second term as president. Clinton, then secretary of state, was about to prepare her own run for the presidency. Released from house arrest in November 2010, Suu Kyi had just been elected to the Myanmar Parliament in a by-election that her party had won in a rout. In a country where any unauthorized assembly had until recently been illegal, tens of thousands of people had greeted Obama’s motorcade. Later, he would address the Burmese people at the University of Yangon, which had been shuttered since shortly after students were gunned down in the pro-democracy protests that followed Suu Kyi’s 1988 entry into politics. It felt as if a heavy shroud was being lifted off the country.

At her house, Suu Kyi spoke with pride about the work that her political party, the National League for Democracy (NLD), was doing in Parliament, challenging the military and learning the intricacies of parliamentary maneuvers—the nuts and bolts of the democracy she said she wanted to build. In her years as a political prisoner, Suu Kyi—the daughter of Aung San, who led the country to the brink of independence in the 1940s—had become a potent symbol, an international icon of resistance against the military junta and the repository of the Burmese people’s remaining hopes. But she spoke to us as though she had no interest in being an icon. “I have always been a politician,” she told Obama firmly in her British-accented English.She had survived detention, house arrest, and attacks on her life; her bravery, eloquence, and persistence had won her the Nobel Peace Prize.

After the meeting, as Obama’s motorcade snaked through a throng of Suu Kyi’s supporters, many of them holding posters with her face on it, he said something in the back of the limo that has stuck in my mind. “I used to be the face on the poster,” he said. “The image only fades.”

At the time, that seemed unlikely: Suu Kyi’s reputation still put her at the celestial heights occupied by the likes of Václav Havel, Lech Wałęsa, and Nelson Mandela. Since joining the country’s political resistance in 1988, she had survived detention, house arrest, and attacks on her life by the ruling junta; her bravery, eloquence, and persistence had won her the Nobel Peace Prize in 1991 and made her the world’s most prominent dissident. “The only real prison is fear,” she famously wrote, “and the only real freedom is freedom from fear.”

But Obama was prescient. The government Suu Kyi is now a part of—in April 2016 she became state counselor, a role similar to prime minister, after her party won a national election—has curtailed civil liberties and press freedoms, and carried out what the United Nations high commissioner for human rights has called “a textbook example of ethnic cleansing.” Others have called it a genocide. Since 2017, more than 700,000 Rohingya Muslims have been forced across the border to Bangladesh, into refugee camps, where disease is rampant and the children are malnourished and have almost no access to education.

Myanmar—formerly Burma (the junta changed the name in 1989)—is a complicated country with a complicated history. The ancient kingdoms of Burma had frontiers that for thousands of years ebbed and flowed with the fortunes of its neighbors. In 1948, after more than a century of British rule followed by years of brutal Japanese occupation, the country achieved independence; since then, it has endured continuous and overlapping civil wars—the longest-running in the world—between the military and the country’s various ethnic groups. (Some 65 percent of the population is ethnic Bamar, but there are more than 100 other ethnicities, dozens of which have taken up arms over the years.) The military has ruled the country either directly or indirectly since 1962. In 2011, stifling martial law gave way to a partial opening: Political prisoners were released, relatively free elections were held, and the government began to plug Myanmar into the internet and the global economy. But modern Myanmar has never known peace or controlled all of its borders.

The status of the Rohingya, who live in Rakhine State—which borders Bangladesh to the north and the Bay of Bengal to the west—has long been at issue. Many Burmese deny that the Rohingya are a distinct ethnic group, referring to them as Bengalis—unauthorized immigrants from Bangladesh. This was codified into law in 1982, when legislation denied citizenship to anyone who had come to Myanmar during British rule; the junta used this law to deny citizenship to all Rohingya. In the late ’70s and again in the early ’90s, the military launched operations that brutally drove more than 300,000 Rohingya into Bangladesh.

Many Burmese resent people of South Asian descent, in part because when Britain governed Myanmar (then Burma) as part of India, it put Indians in positions of authority. And many Burmese Buddhists fear the fate of countries such as Afghanistan and Indonesia, where an intolerant strain of Islam—at times financed by Saudi Arabia—has supplanted Buddhism. (Suu Kyi has spoken with me of those fears herself.) As an ethnic minority, as Muslims, and as people who came from the Indian subcontinent, the Rohingya are thrice vulnerable. A Rohingya human-rights activist named Wai Wai Nu, who was imprisoned by the junta for several years, told me, “It’s all about power—keeping Burmese Buddhist power.”![]() Barack Obama and Aung San Suu Kyi arrive at a press conference at her residence in Yangon. November 14, 2014. (Mandell Ngan / AFP / Getty)

Barack Obama and Aung San Suu Kyi arrive at a press conference at her residence in Yangon. November 14, 2014. (Mandell Ngan / AFP / Getty)

A few months before Obama’s 2012 meeting with Suu Kyi, Muslim men in Rakhine State had allegedly raped a Buddhist woman. In response, Rakhine Buddhists attacked the Rohingya, burning their villages; ultimately more than 100,000 Rohingya were displaced into squalid camps. Conditions for the estimated 1.1 million Rohingya in Rakhine State became more precarious. In late 2016 and early 2017, attacks by Rohingya insurgents led to wildly disproportionate responses by the Burmese military, culminating in the systematic expulsion of those 700,000 Rohingya into Bangladesh amid allegations of horrifying violence.

Suu Kyi has done little to stop the atrocities. Her seemingly callous indifference has felt to many outsiders like a betrayal. How can Suu Kyi, an avatar of human rights for so many years, stand by while her government violently tramples them? Western politicians and media have heaped criticism on her; many of the organizations that championed her cause are rescinding the awards they once rushed to give her. But Suu Kyi has refused to shift course. “The obstinacy that made her into an icon makes her dig in,” a Western diplomat who has worked with her told me. “She likes the adulation and the prizes—but in the end she thinks she’s right and they’re wrong.”

During my eight years in the Obama administration as a deputy national security adviser, I met with Suu Kyi a number of times, in a variety of places: at her family home in Yangon; at the Parliament and her state counselor’s suite in Naypyidaw, the capital; and in Washington, D.C. I believed her commitment to human rights was sincere. But then, Suu Kyi has always been good at making people believe the things she says—at making people believe in her. And many in the West were too eager to anoint her as a savior. Looking back, I realize, she has always contained multitudes—the idealist, the activist, the politician, the cold pragmatist.

“She always called it a second Burmese revolution,” Ambassador Mitchell said to me, referring to the political resistance that she helped fuel in 1988. “Now that she is in a position of power, what did it mean? What was it all about?”

2. Dissident Daughter

One key to understanding Aung San Suu Kyi and her appeal in Myanmar is familial: She is her father’s daughter.

Aung San founded the modern Burmese military in 1941. He fought alongside the Japanese to rid Burma of British colonialism, then fought alongside the British to rid Burma of Japanese domination, then negotiated Burma’s freedom from the British. As the country approached independence, he was seen as the only figure with the stature to potentially unite its political factions and ethnic groups. But in 1947, he was assassinated at the age of 32. Unlike Mao Zedong or Jawaharlal Nehru or Suharto, Aung San would never be diminished by power. As Burma descended into civil war, dictatorship, and grinding poverty, he would remain forever uncorrupted, a symbol of the lost promise of independence.

When her father was killed, Aung San Suu Kyi was 2. She went on to attend school in India, then studied at Oxford, where she met her husband, Michael Aris. She had two sons and settled down in England with plans to get a doctorate in Burmese literature. Her entry into politics was an accident. In the spring of 1988, Suu Kyi traveled back to Yangon to be with her mother, who had just suffered a stroke. At that same time, Burmese students—infuriated by repression and by a monetary policy that had wiped out people’s savings—were organizing underground cells and public protests. The junta responded with force, shutting down the universities and shooting students in the streets. Many of the wounded were taken to the hospital where Suu Kyi had been caring for her mother, giving her a bloody, close-up view of the regime’s brutality.![]() Suu Kyi (front center) at age 2, in 1947, with her father, Aung San; her mother, Daw Khin Kyi; and her brothers. Her father was assassinated later that year. (Kyodo News / Getty)

Suu Kyi (front center) at age 2, in 1947, with her father, Aung San; her mother, Daw Khin Kyi; and her brothers. Her father was assassinated later that year. (Kyodo News / Getty)

Learning that the daughter of Burma’s national hero had returned to her homeland, the students—who would become known as “the 88 Generation”—recruited Suu Kyi to their cause. Aung Din was one of the students who met with her at her house on University Avenue. “She was smart,” he told me recently. “She listened. She was completely different from the politicians we’d seen. She didn’t have any agenda. She just loved the country.” She agreed to speak at a rally at Shwedagon Pagoda, a sprawling complex of Buddhist temples. “We didn’t realize it would be quite this big,” Aung Din said, chuckling as he recalled the scene. Half a million people showed up to see her. Standing in front of her father’s portrait, Suu Kyi called for multiparty democracy and spoke perhaps the most famous words in the history of Burmese politics: “I could not, as my father’s daughter, remain indifferent to all that is going on. This national crisis could in fact be called the second struggle for national independence.” The students started the movement; she became its hero.

The junta cracked down. Students were beaten and rounded up, and some were killed. In April 1989, Aung Din was arrested and put into solitary confinement. Meanwhile, Suu Kyi quickly took to her role as a principled opponent of the regime. During the run-up to an election that the junta permitted in 1990, she gave thousands of speeches around the country. In the town of Danubyu, a line of soldiers cocked their weapons, pointed them at her, and commanded her to leave. She kept walking toward the soldiers even after they had been given the order to fire, demanding that she be allowed to pass. The soldiers stood down. The daughter of Aung San would not be martyred.

The NLD won the 1990 election in a landslide, but the junta ignored the results. Over the next two decades, Suu Kyi spent most of her days under house arrest at 54 University Avenue, where her mother had lived until her death in 1988. The military ran propaganda campaigns against her, painting her as a prostitute and a tool of the West. In Myanmar, where even saying her name was for a long time a crime, people called her “The Lady.” Beyond Myanmar’s borders, she acquired a mystique that grew out of her self-sacrifice: She refused repeated offers from the military to let her return to England. With the help of the internet, pro-democracy activists used the template of the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa to build what one Burmese intellectual calls an “organizational superstructure” around her.She would look up at her father’s photograph and think: It’s you and me, Father, against them.

Derek Mitchell first met her in 1995, when he was working for the National Democratic Institute, an international nonprofit. He sat in her house, nestled on the shore of Inya Lake, a peaceful body of water ringed by the homes of prominent people—including, in those days, Ne Win, the military dictator who had ordered Suu Kyi’s imprisonment. “We were interested in what she was interested in, which was democracy,” Mitchell told me. “She made us feel like we were a part of her movement, and you got a sense of this incredibly strong person holding up an incredibly sad, broken country,” he recalls. “So I think a lot of people came away feeling, How can we help her? We have to help her.”

“Don’t forget us,” Suu Kyi told him. “There’s a light shining on me because I was just released, but then it will fade.”

She was right. The rising democratic tide of the 1990s did not reach Myanmar. In 1999, her husband died of cancer in Britain. The junta denied his dying wish to visit her, and she refused to leave her country to be with him. She was placed back under house arrest, often in extreme isolation. During another of her brief releases, in 2003, the junta unleashed a mob of more than 1,000 men to engulf her motorcade. She narrowly escaped violence that killed dozens of people, but was again imprisoned.

Through the ’90s and 2000s, Suu Kyi lost her family, her freedom, and any semblance of normalcy. She had no way of knowing whether her story would have a happy ending. She had every reason to fear that the military her father had founded would end her life. But she leaned on an inner fortitude. She once explained how central her father was to this strength, saying, “I would come down at night and walk around and look up at his photograph and feel very close to him … It’s you and me, Father, against them.”

In November 2010, as the junta took the first tentative steps toward enhancing its popular standing at home and improving relations with the United States and the West, Suu Kyi was once again released from house arrest. She remained wary. When Kevin Rudd, who was then Australia’s foreign minister, traveled to see her, she told him that she wouldn’t campaign for a seat in Parliament unless the Burmese government provided assurances that her security would be guaranteed, which it subsequently did, in writing. “She was petrified that she’d be killed,” Rudd told me recently. But she ran anyway, and won.

3. Opposition Leader

“Well, what is it you want to say to me?” Aung San Suu Kyi asked with a distinct chill. It was the summer of 2013, and I had come to Myanmar carrying a letter from President Obama. The crisp white envelope sat, unopened, on a table between us. We were in Naypyidaw, sitting on couches in an anteroom of the Burmese Parliament. As the leader of the opposition in Parliament, she was unhappy that Obama had welcomed Thein Sein, then the president of Myanmar, to the Oval Office. One purpose of my visit was to reassure her that the Obama administration’s policy was still focused on bolstering democracy, whose successful future in Myanmar she—and most Burmese—believed was dependent on her.

Myanmar was in transition. The junta’s decision to open up the country was related to events and trends that went beyond Suu Kyi and the Western sanctions aimed at supporting her: In 2008, Cyclone Nargis had killed tens of thousands of people and exposed the ineptitude of the government; the relative prosperity of Southeast Asian neighbors such as Singapore and Vietnam suggested that connection to the outside world was better than isolation; and public resentment of Myanmar’s dependence on China was putting pressure on the regime.

But Thein Sein was liberalizing the country faster than expected—perhaps even faster than the military intended. By early 2012, most of Myanmar’s political prisoners had been released, and exiles had been welcomed home. The government was beginning to respect free-speech rights, as well as the freedom to assemble and to form unions. A peace process with more than a dozen separate ethnic insurgencies was on the cusp of yielding cease-fires. In response, the U.S. and other countries had begun to lift sanctions. “Part of Suu Kyi’s anger with Thein Sein,” Richard Horsey, a Myanmar-based political analyst, told me recently, was that “he was doing all the things that she’d imagined she should be doing. She was going to be the person who brought about the rapprochement with the West. She was going to be the one who did all the reform—and then suddenly she found there was this guy doing it and getting a lot of credit for it.”

A glaring exception to this democratic progress was the government’s handling of the Rohingya. Before my 2013 meeting with Suu Kyi, I had met with U Soe Thein, the president’s closest adviser. When I pressed him on the Rohingya, he detailed the government’s steps to reduce tensions, permit humanitarian access for groups such as Doctors Without Borders, and allow individuals to apply for citizenship—but the government would issue citizenship cards only to those who stopped calling themselves Rohingya, and few would do that. “The situation is very complicated,” U Soe Thein told me. “We aren’t going to change the views of the local Rakhine or the people in Burma.”

In my meeting with Suu Kyi, I told her that the Obama administration still supported a full transition to democracy, as well as amendments to the constitution to restore civilian control of the military. But I emphasized the importance of the ongoing peace process with the ethnic groups and told her that the U.S. was concerned about the plight of the Rohingya. “We will get to those things,” she said. “But first must come constitutional reform.” To her, progress on human rights was inseparable from her core agenda. “We cannot have human rights without democracy,” she insisted.

In formal meetings, Suu Kyi’s whole body seemed to reflect her stoic discipline; she sat with ramrod posture and moved with care, as though conserving energy. But when the conversation shifted toward small talk she relaxed, smiled easily, and became a charming host, talking warmly about the Obama family’s dogs. “I am sure they are more behaved than my own dog,” she said. Suu Kyi loves pets and pop culture with the intensity of someone long denied simple pleasures. She was happy that Ambassador Mitchell and I had brought along a DVD she had requested: Glory, the underdog story of an all-black regiment during the United States’ Civil War.

Suu Kyi was one of the few people I met while in government—others include the Queen of England, Raúl Castro, and the Dalai Lama—who made exactly the impression on me I expected them to. Her regal manner, elegant Burmese clothes, and Oxford English, along with the ever-present flower in her hair, lent her a kind of ethereal charisma. She seemed to straddle different worlds—East and West, inexperienced in government yet accomplished, imprisoned and free. Her stubbornness and her flashes of temper only reinforced this: Given what she’s been through, I would think, no wonder she’s angry and stubborn. Her lack of specificity—her idealism can be platitudinous—allowed others to project their own beliefs onto her, and made them feel that her cause was their own.

4. Candidate

In 2015, I again traveled to Myanmar as an emissary of President Obama; a general election was just a few months away, and I was there to urge the government to hold a credible vote—and to respect the results. In cavernous government buildings, I sat opposite senior Burmese officials in rooms the size of football fields. My first trip to Myanmar had come soon after the Arab Spring, when countries seemed to be shaking off the yoke of autocracy; this time, the Burmese inquired about U.S. relations with Egypt and Thailand—two countries that had recently experienced military coups. President Thein Sein seemed exasperated by my entreaties on behalf of the Rohingya, but like the other ruling-party officials I met with, he committed to respecting the result of an election that was almost certain to go against him.

In her house in Yangon, Aung San Suu Kyi was energized, once again embracing the role of an outsider. For weeks, she’d been campaigning across the country. She made no secret of the fact that while her party, the NLD, was running a slate of candidates, she saw the election as being about her. She took a particular interest in the communications role I had played in Obama’s 2008 campaign. “How did you make sure all your people were communicating the same message?” she asked me. Like two campaign strategists, we discussed how to coordinate surrogates.

Suu Kyi’s main concern was whether the United States would call the upcoming elections “free and fair.” From her perspective, the elections could not be free and fair, because the military still refused to reform the constitution. I assured her that we would not refer to them that way—though largely because the Rohingya were still prevented from voting under the 1982 citizenship law.The scorched-earth campaign against the Rohingya has allegedly included mass rape, extrajudicial executions, and the destruction of hundreds of villages.

On election day, the mood in the country was—as David Mathieson, who worked for Human Rights Watch in Myanmar for many years, put it to me—a kind of “Fuck them, we did it!” euphoria. Before the results were even known, people celebrated in the streets. Car horns honked. For the first time in their lives, people cast a consequential vote against the military. The NLD won more than 80 percent of the vote—enough for an outright majority in Parliament but, given the military’s entrenched position and prescribed 25 percent bloc of votes, not enough to reform the constitution. After a futile postelection effort to negotiate constitutional changes that would have allowed Suu Kyi to be president—she remains constitutionally barred from the office by an amendment written specifically with her in mind (it prohibits those with non-Burmese children from being president)—the NLD created the position of state counselor, which granted her what powers the party could. But even those powers were limited: The constitution also prevents civilian control of the military, and leaves the military responsible for the three ministries—Defense, Border, and Home Affairs—that subsequently carried out the attacks on the Rohingya.

Still, Myanmar had its first peaceful transfer of power in more than half a century. It seemed to be a miraculous transition in a world where democratic miracles no longer happen.

5. State Counselor

In the summer of 2016, I once again met with Suu Kyi in Naypyidaw. Now she was one of the officials occupying a cavernous government building, surrounded by the trappings of power. When she became state counselor, the Obama administration urged her to lay out a vision for the country. Instead, she largely retreated into isolation in Naypyidaw. As one of her advisers told me, Suu Kyi’s mind-set was: “People will judge us for what we do, not what we say.” She launched a peace process modeled on her father’s efforts to unite the ethnic groups—cease-fires that would lead to negotiations and, ultimately, a federal system in which each ethnic group had a formal degree of autonomy while still being part of a national union. And she began efforts to reform Myanmar’s deeply dysfunctional economy, which had been set up on a command-and-control basis so the military could guard its resources and remain in power. While she’d long been in favor of the U.S. maintaining some sanctions on Myanmar, she had come to recognize that they had a crimping effect on the investment the country needed to reform its economy. I told her that, with her assent, the Obama administration would likely lift the sanctions.

When I said the administration was concerned that the Burmese government’s treatment of the Rohingya was both a humanitarian crisis and a threat to the country’s broader transition to democracy, she told me she was appointing a commission, led by former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan, to study the issue and make recommendations. “I told Kofi that I wouldn’t ask him to do this if I wasn’t serious about it,” she said. Sounding like the idealistic Aung San Suu Kyi I’d long admired, she also said she wanted to initiate a dialogue between Rohingya women and Buddhist women in Rakhine State. Unlike most of the military officials I’d met, she never referred to the Rohingya as Bengalis. (Neither has she referred to them as “Rohingya” in public, however. She instead calls them “Muslims in Rakhine State.”)

As she walked me out of the building, she talked about her workload and how she’d looked to the example of Margaret Thatcher, who worked notoriously long hours at the center of a male-dominated system. She also asked me about the upcoming U.S. election. Hillary Clinton, I assured her, would continue to be focused on Myanmar. “Yes,” she said with a somewhat scolding tone. “But you don’t know who is going to win.”![]() Suu Kyi at a ceremony marking the 100th birthday of her father, the hero of Burmese independence. February 13, 2015. (Ye Aung Thu / AFP / Getty)

Suu Kyi at a ceremony marking the 100th birthday of her father, the hero of Burmese independence. February 13, 2015. (Ye Aung Thu / AFP / Getty)

By the time she visited Washington a few weeks later, in September 2016, the White House had decided to lift the sanctions. During a breakfast at Vice President Joe Biden’s residence, she made the case to congressional leaders that Myanmar “could stand on our own.” Watching her, I saw deft political skill—she asked Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell about his horses, and Representative Joe Crowley of New York about his mother. Yet she spoke icily to Senator Bob Corker, from Tennessee, about a U.S. decision to publicly chide Myanmar for its poor handling of child trafficking. “We will take care of our own children, Senator,” she concluded, after a long lecture. She wanted Western support, but she was adamant about national sovereignty.

The U.S. decision to lift sanctions was controversial; some people have blamed it for the escalation of violence involving the Rohingya. In October, the newly established Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) attacked three Burmese border posts, killing nine police officers, and raising fears of further attacks. The military—which had been caught unawares—responded with brute force, displacing some 30,000 Rohingya. Lifting the sanctions “gave a real sense of impunity to the military,” Sarah Margon, who runs the Washington, D.C., office for Human Rights Watch, told me. Others, such as Wai Wai Nu, the Rohingya activist, have told me the same thing.

I understand this argument, but I’m skeptical that sanctions are ever an effective deterrent. I have come to believe that sanctions are generally overused by Washington; the bad guys know how to evade them, so they hurt only the wrong people. In Myanmar, this means bad actors thrive in the dark economy of trading drugs, rubies, and jade while the broader public stagnates in a sclerotic economy that can’t attract investment. Moreover, a Myanmar that is economically stymied by the U.S. is more likely to fall into the arms of China, which won’t raise any human-rights concerns about the Rohingya.The moral stain of the ethnic cleansing may prompt international condemnation, but it hasn’t caused Suu Kyi to pay much of a political price at home.

In August 2017, the commission chaired by Kofi Annan issued a comprehensive set of recommendations—including lifting all restrictions on the Rohingya, and offering them a path to citizenship—that, if implemented, could go a long way toward improving the Rohingya’s safety and legal standing in Myanmar. But two days after the report was released, ARSA attacked more than 30 police posts, killing another 12 Burmese security personnel; in all, 71 people died. This time the military was ready. “They had nine months to think about what they would do if a bigger attack came,” Richard Horsey, the political analyst, told me. “They decided they would strike back extremely hard, and that if ARSA was going to hide among the villages, then there would just be no villages.” Throughout the fall of 2017, this scorched-earth campaign against largely defenseless Rohingya allegedly included mass rape and sexual assault, extrajudicial executions, and the destruction of hundreds of villages; this was no mere counterinsurgency campaign. Of the 700,000 Rohingya who were driven into overcrowded camps in Bangladesh, 400,000 were children.

It’s possible that the military wanted to embarrass and undermine Suu Kyi, who did not have the formal power to stop the attacks. But Suu Kyi has not shown any empathy for the Rohingya and has taken little action to help them: Her public comments have downplayed the abuses, and she’s allowed herself to become something of a shield for a military that wants to keep the international community out of Myanmar’s affairs. “She has not only failed to protect this population, but she supported the military agenda,” Wai Wai Nu told me. Despite Suu Kyi’s rhetoric on human rights, since becoming state counselor “she has never met with any Rohingya political leaders, even though she knows them very well,” she noted.*

One of those leaders is Wai Wai Nu’s father. “Once we are in power,” she said Suu Kyi had told her father years ago, “these things will be solved.”

6. Faded Icon

I returned to Myanmar in January. The impact of the country’s opening to the West was visible in the new glass buildings filling Yangon’s skyline, and in the heavy traffic from the airport. The impact of the Rohingya crisis was evident in the vacancies at the new downtown hotel I stayed in; though economic sanctions have been lifted, news coverage of the country as a place of atrocities has caused Western tourism and investment to dry up. I walked by 54 University Avenue. The house was empty; Suu Kyi lives most of the time in Naypyidaw. Two booths outside the property were manned by a small group of police officers who chatted on folding chairs. Feral dogs roamed the sidewalk. Signs for the NLD were on display, along with a picture of Suu Kyi.

Down the street, in a coffee shop that wouldn’t be out of place in Brooklyn, I met Cheery Zahau, a human-rights activist and an ethnic Chin, a persecuted Christian minority in Myanmar. Though the very fact that we were meeting represented an advance of freedom—a few years ago, our conversation would have been illegal—Cheery Zahau was critical of the pace of liberalization and the lack of protection for the Rohingya. She complained that the West did not probe beneath Suu Kyi’s rhetoric about human rights. “Your government never asked tough questions,” she told me. “The EU did not do it. The UN did not do it. We ethnic people did not do it. Nobody.” She believes Suu Kyi’s main preoccupation has been her own ascent, cloaked in the language of human rights, and that she was now jockeying for power with Than Shwe, the 86-year-old former junta leader who still wields enormous influence. “Than Shwe and Aung San Suu Kyi compete for a chair,” she said. “It’s not a matter of how to improve things. It’s a matter of who gets to sit on that chair and be the boss.”

I heard variations of this critique throughout Yangon. The former student leader Aung Din, who had devoted much of his life since 1988 to bringing democracy and human rights to Myanmar’s people, told me civil-society organizations that had been key supporters of the NLD could no longer count on the support of Suu Kyi’s government.![]() A portrait of Suu Kyi’s father hangs in a coffee shop in Yangon, at a time when the ruling military junta had made such images illegal. January 1, 2009. (Jerry Redfern / LightRocket / Getty)

A portrait of Suu Kyi’s father hangs in a coffee shop in Yangon, at a time when the ruling military junta had made such images illegal. January 1, 2009. (Jerry Redfern / LightRocket / Getty)

Aung Zaw, one of Suu Kyi’s student bodyguards in 1988, ended up fleeing the country and helped found The Irrawaddy, a prominent independent newspaper. Around the time Suu Kyi was elected to Parliament in 2012, he—like many others—returned to the country filled with optimism. That optimism has given way to weariness. “We had much more space during Thein Sein’s government,” he told me. The previous day, prison sentences for two Reuters journalists who reported on Rohingya massacres had been upheld. (They’ve since been pardoned as part of a general amnesty.)

Some say that this backsliding on civil liberties can be attributed to the military reasserting itself and drawing Suu Kyi into protracted political jockeying in the capital city. After imprisoning her in her home for decades, “now they’ve detained her in Naypyidaw,” Aung Zaw joked. Many people close to Suu Kyi speculate that she is quietly negotiating constitutional changes with Than Shwe. But some critics see her as embracing a kind of royalism: Her decision making is centralized, and a tight circle of advisers limits the information that reaches her. More than one person I spoke with suggested that while Nelson Mandela was both a hero and a politician, Suu Kyi is more of a queenlike figure.

On a Monday morning in Naypyidaw, the nearly empty highway from the airport—which yawns to a seemingly impossible 20 lanes—posed a stark contrast to Yangon’s clogged arteries. Concrete bleachers lining the road hint at the grand, North Korean–style military parades that the junta once had in mind: The city was built in secret, unveiled in a surprise announcement by the military in 2006.

I met with Thaung Tun, whom Suu Kyi had appointed as both national security adviser and minister for investment and foreign economic relations. A former diplomat, he emphasized that a gradual shift from military to civilian control was happening. Within days, he said, the General Administration Department—a bureaucracy that helps run the country down to the village level—would be moved from military to civilian authority, a tangible albeit incremental achievement. Other Suu Kyi advisers made the case to me that she’ll be in a stronger position to advance her agenda after the 2020 Burmese election, so she’s biding her time until then.

I asked Thaung Tun about the Rohingya. They would be welcomed back from the camps, he said, but would have to prove that they are from Myanmar. “You have the same issue in the southern United States,” he said. “If they want to come, it has to be an orderly process … In Texas they say, ‘We need this wall because we can’t have them all coming in, but we need some of them to come in and work.’ ”

This wasn’t the only creative interpretation I heard about what is happening in Rakhine State. When I sat down with Aung Tun Thet, an economist Suu Kyi appointed in 2018 to yet another commission investigating the Rohingya crisis, he called allegations of atrocities “only allegations based on anecdotes from the refugees in Bangladesh.” This ignores the fact that the UN and other organizations had to rely on anecdotes because the government of Myanmar denied access to Rakhine State. “The issue is a complex one and not a black-and-white case,” he said. “The crisis began with the armed attacks by the terrorist group ARSA, and the response of the security forces which resulted in the mass movement into Bangladesh.”

The government official responsible for managing the repatriation of the Rohingya is Win Myat Aye, the minister of social welfare, relief, and resettlement. We sat in a large room featuring a mural that depicted a goddesslike figure in a gold helmet pulling a young girl from a stormy sea. The minister told me the government of Myanmar is committed to taking back the refugees. But then he listed the obstacles he faced: Some of the Rakhine people don’t want the Muslims to come back, he said; relations with Bangladesh are strained; only two reception centers are in operation. Thus far, a mere 200 Rohingya have returned. When I pressed him on the insecurity that awaited the rest, he spoke of the need for “social cohesion” and “economic development.” When I asked about the scale of the challenge—resettling hundreds of thousands of displaced people—he seemed overwhelmed, and broke from his talking points. “We are always trying our best,” he said, pointing out the work of his office during natural disasters such as floods and storms. “When we meet with the Muslims, these people are our friends.”

I walked out into a silent and largely empty parking lot. Naypyidaw can be eerily quiet; the powerful are out of sight, tucked away in ministry buildings and mansions built by the generals. The chilling truth is that the moral stain of the ethnic cleansing may prompt international condemnation, but it hasn’t caused Suu Kyi to pay much of a price at home or to alter her approach to politics. Indeed, I could see her logic: proceed cautiously, court the old guard, get the military comfortable with civilians running the government, create a broader base for economic growth, don’t rock the boat. Aung Zaw cautioned me against reading too much into the dissatisfaction with Suu Kyi in urban areas, because she maintains deep support in the countryside. “Outside of the cities,” he said, “people are patient.”

As her decades of resistance showed, Aung San Suu Kyi is more than capable of being patient.

Whether or not Suu Kyi has changed, the world around her has. Democratizing Myanmar “would have been easier two decades ago,” says Thaung Tun. He’s right. Twenty years ago, democracy was on the march, authoritarian China wasn’t yet flexing its muscles, neighboring India hadn’t turned decisively to Hindu nationalism, a liberal United States was the sole underwriter of the international order, terrorism was a peripheral threat, and the Pandora’s box of social media had not yet been opened.The hope Suu Kyi once embodied now resides in those who have picked up her torch.

Chinese influence in Myanmar is growing. One of China’s biggest projects—part of its signature Belt and Road Initiative—is the construction of a deep-sea port on the coast of Rakhine State. China’s ambitions for Myanmar also feature oil and gas pipelines to feed its insatiable energy needs. One of the pipelines cuts right through Rakhine State—suggesting an incentive for the Burmese military’s aggressiveness against the people living there.

The Rohingya crisis presents an opportunity for China. As Myanmar faces Western condemnation, it will become more reliant on China for investment, and for protection at the UN. “If we are rejected by our friends from the West,” Thaung Tun told me, “then we will have to look elsewhere.” China also offers an autocratic model for dealing with Muslim minorities, justifying poor treatment on counterterrorism grounds: Reportedly at least 1 million Uighurs—a Turkic, predominantly Muslim minority—are being held in what the Chinese government calls “counterextremism training centers” but one UN panel has called “something resembling a massive internment camp,” in Xinjiang province.

If China represents unbridled authoritarianism, Facebook has spread the perils of unbridled openness. In Yangon, I met with Jes Kaliebe Petersen, a Danish entrepreneur who works in the emerging Burmese tech sector. He explained how telecommunications reform in 2014 transformed Myanmar, which leapfrogged from minimal internet access to almost 90 percent penetration in less than five years. People don’t have computers, so the internet is accessed almost entirely through the Facebook app on phones. The result has been an explosion of hate speech. Imagine living with little access to nonstate media, and then suddenly believing you had access to everything—only the information is sensationalist fearmongering, much of it false, driven into your feed by an algorithm. Petersen said every minority group has been targeted, particularly the Rohingya.

Looking back, I agonize over whether the Obama administration could have done more to prevent the escalation that has taken place in Rakhine State. Doing so makes me sympathetic to the paucity of good options available to the current White House: While levying punitive measures will only push Myanmar closer to China, engaging more deeply with the current government risks rewarding it. But President Donald Trump hasn’t been engaged at all; he has said nothing publicly about Myanmar or the Rohingya, nor has he spoken with Suu Kyi. His rhetoric about Muslims and illegal immigration echoes what you hear in Naypyidaw, and his closed door to refugees undercuts U.S. leadership in resettling displaced peoples. The Burmese national security adviser, echoing his American counterpart, John Bolton, dismisses the International Criminal Court, a potential source of leverage against perpetrators of ethnic cleansing. The ICC, he told me, “should not apply to the U.S., Israel, or Myanmar.”

Nationalism, the spread of authoritarianism, an illiberal American administration, fears of terrorism, a society ravaged by social media—as these roiling currents swirl around Myanmar, Suu Kyi has been unwilling to rise above them. In June, she met with Viktor Orbán, the autocratic leader of Hungary, publicly allying with him on the challenge of managing Muslim immigration.

7. The Future of Myanmar?

Some seven years after I first met her, I’m left with a question: What does Aung San Suu Kyi want?

There is no doubt that she wants to be the president of Myanmar; she wants to sit in the chair. But why? One answer is that she just wants power over a Buddhist Burma—to claim her rightful inheritance as Aung San’s daughter, to realize her destiny as the heiress who has sacrificed for the throne; democracy, in this view, is just a means to realizing a personal ambition. Acting on behalf of the Rohingya could imperil that goal by undermining her political standing.

A more charitable answer is that she truly does want to transform the country into a democracy—to restore civilian control over the military, to make peace among the ethnic groups, to build a country where people’s lives steadily improve and where ethnic cleansing is unthinkable—and that requires patience and unsavory compromises.

Both answers, I believe, are accurate. In my encounters with her over the years, I have seen both the idealism she embodies and her will to power. I can recall a woman who spoke of the imperative of national reconciliation; who stressed nonviolence and dialogue; who insisted that she was not an icon, merely a politician trying to lead a political party in a messy, emerging democracy—the woman who asked for a DVD of Glory, a story of tragic heroism in pursuit of freedom and equality. I can also recall a woman who had a persistent habit of steering the conversation back to her own ambitions; who easily discarded old liberal allies who had stood by her while she was imprisoned; whose rhetoric about human rights and the rule of law was often gauzy and laced with the language of sovereignty—the woman who, the last time we talked, told me she was interested in The Crown, the drama about the life of the British monarch.

David Mathieson, who supported her for years at Human Rights Watch, told me that Suu Kyi’s fall from grace offers a lesson about resting all of our hopes in one individual—the weight of a country is too heavy to place on one person’s shoulders, no matter how alluring her story. This rings true to me, and speaks to a failure by many of us in the West, who are guilty of sometimes viewing political dilemmas in complicated countries as simple morality plays with a single star at the center. But that doesn’t absolve Suu Kyi of the stark betrayal of what she once wrote: “Fear of losing power corrupts those who wield it, and fear of the scourge of power corrupts those who are subject to it.”

The situation in Myanmar is not hopeless, but it depends on investing our aspirations in more than one person. I believe that what Suu Kyi once embodied now resides in those who have picked up her torch. Zin Mar Aung, an NLD parliamentarian and former political prisoner who spent nine years in solitary confinement, still believes Suu Kyi’s example can be a “message for the next generation … With all of the conflicts in our country’s history, we don’t want to solve the problems using force.” Activists are more critical, but have a similar perspective. Suu Kyi “is not consistent with what she was saying; she’s not following her own words. That breaks our heart,” a young activist named Thinzar Shunlei Yi told me. “And we now, internalizing her words, cannot accept it. We truly think that somebody who had strong principles, who kept on going whatever the situation—that’s how we are doing. That’s how, as an advocate, as a human-rights defender, we have to be.”

Nearly everyone I spoke with said Myanmar had been traumatized by more than half a century of repression—trauma from which it would take a long time to heal. “Every generation since independence is worse off than the one before,” the historian Thant Myint-U told me. “That’s a tremendous psychological burden.” Another pro-democracy activist told me that after 1988, “people died inside”; they became, she said, “small mice in a laboratory.” We should not underestimate the damage that such enduring oppression might have done to Suu Kyi herself, as many people I spoke with in Myanmar suggested sotto voce.

The best scenario would have Suu Kyi spending her remaining years as a bridge to an imperfect yet more developed, and less traumatized, democracy and society. This will not be easy—not at a moment when the world is being overwhelmed by authoritarianism and tribalism; not in a country that has already been divided, manipulated, and bludgeoned by tribal appeals for generations. I asked Cheery Zahau, the human-rights activist, what she thought the future held for Myanmar. She told me about how deeply rooted the pain is, how it could even lead the Chin Christian minority she is a part of to turn on a Muslim minority.

“Some Chin pastor called me,” she recounted, “and he said, ‘Cheery, why are you so supportive of the Rohingya? They are Muslims.’ And I was like, ‘Yeah, they are human beings first of all.’ And he said, ‘But the Muslims kill Christians in Syria.’ ”

She paused, letting this sink in. “What do these two things have to do with each other—ISIS killing Christians in Syria, and the Rohingya being poor in their village?” Her voice rose in anger.

Nine months pregnant, she ran a hand over her stomach. “As a society, we really need to heal ourselves … We are so traumatized” by ethnic division, “or just because we have different political aspirations, or just because we have a different faith, or language, or culture … For Burman people like Aung San Suu Kyi or 88 people, they have been oppressed; they’ve been traumatized because they want a different political system. And a large, large population of this country is traumatized from poverty … So all of us have this trauma, and we have not healed. And this is why, for me, human rights is so important as a pathway to improve and heal the society.”

A younger Aung San Suu Kyi would have agreed with that. If the current one does, she will no longer say so.

No comments:

Post a Comment