By John Krzyzaniak

It’s hard to know exactly what happened on August 8, when an accident offshore of the Nenoksa Missile Test Site in northern Russia caused an explosion. But we do know that it left five Russian nuclear scientists dead and caused a spike in radiation levels in the surrounding area. The available evidence has led some US intelligence officials, arms control experts, and President Trump to conclude that the Russians were testing an engine for a nuclear-powered cruise missile (though there are skeptics).

It’s hard to know exactly what happened on August 8, when an accident offshore of the Nenoksa Missile Test Site in northern Russia caused an explosion. But we do know that it left five Russian nuclear scientists dead and caused a spike in radiation levels in the surrounding area. The available evidence has led some US intelligence officials, arms control experts, and President Trump to conclude that the Russians were testing an engine for a nuclear-powered cruise missile (though there are skeptics).

If the suspicions are correct, then this accident (and prior setbacks) show that the Russian quest for a nuclear-powered cruise missile may be a quixotic one. Before pressing on, Vladimir Putin would be well-advised to review some of the myriad problems that the United States’ own nuclear-powered cruise missile program, Project Pluto, experienced in the late-1950s and early-1960s. Below is a brief overview of the technical, environmental, and political challenges that Project Pluto faced.

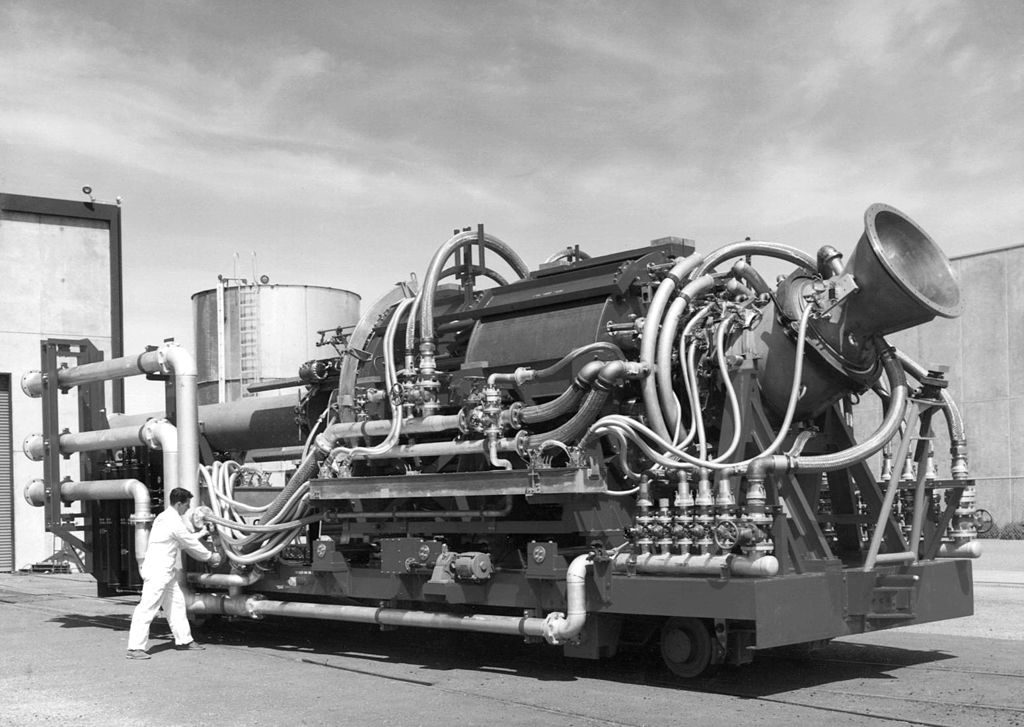

The basic goal was to build a nuclear-powered ramjet engine: bring in cool air at the front, pass it over a nuclear reactor to heat it up and make it expand, and then expel it out the back to provide thrust. This is apparently the same basic design that the Russians have chosen for their modern version. The main advantage of such a system, at least in theory, is that it can fly for a much longer period compared to a chemically propelled one—perhaps for days or even weeks.

Though the concept is elegant and straightforward, there were a host of technical challenges. Theodore Merkle, the director of Project Pluto, identified these in a 1959 report titled, “The Nuclear Ramjet Propulsion System.”

The first challenge was the size and durability of the reactor. Most commercial nuclear reactors are large, heavy, and surrounded by many tons of concrete. This one, by contrast, needed to be small and light enough to fly. But it also had to be durable enough to withstand stress from extreme pressure changes, temperature changes, and the forces created when the missile accelerated or changed course. Each of these forces on its own could be expected to generate pressure on the scale of thousands of pounds per square inch.

Many of Merkle’s points chime with what Soviet scientists working for the USSR’s ministry of defense had already written two years prior. For example, both reports suggest that few if any existing materials would be suitable for making the reactor wall because of the extreme temperatures involved. Additionally, Merkle and the Soviet scientists both alluded to the fact that a nuclear-powered ramjet engine would need a second form of propulsion for launch, adding yet additional complexities.

All in all, the technical challenges led Merkle to propose in his report no fewer than 10 “major research and development areas which must be entered if one wishes to actually produce such an engine.”

Among the issues that didn’t much concern Merkle, however, was the prospect of spewing fission fragments out of the reactor and into the atmosphere. He calculated that a 490-megawatt reactor “might produce somewhat less than 100 grams of fission product,” and that “the quantity released into the air stream might be a few grams.”

Edwin Lyman, acting director of the nuclear safety project at the Union of Concerned Scientists, recently contextualized Merkle’s assessment. In an email to Defense One, Lyman noted that at the time, “nuclear weapon states were still engaged in atmospheric testing, [so] there wasn’t a whole lot of concerns about releasing additional radioactivity into the environment.” Attitudes have obviously changed since then. Moreover, Lyman points out that “to characterize radiation releases in terms of ‘grams’ is misleading. Chernobyl released only a few hundred grams of iodine-131 yet it resulted in thousands of thyroid cancers among children.”

Beyond that, if it were ever deployed, the Project Pluto missile would fly “at near-treetop level at three times the speed of sound,” according Gregg Herken, a Cold War historian who wrote about Project Pluto for the April/May 1990 issue of Air & Space Magazine. This “flying Chernobyl” would not only create a deafening roar of 150 decibels but also produce a lethal shockwave—not to mention the wake below the missile, which the red-hot reactor would also probably scorch.

It’s almost shocking, then, that the project continued for seven-and-a-half years before people realized that the environmental and health-related problems would, in turn, lead to political problems. First, where would one test-fly a nuclear reactor? If a test in the Nevada desert went awry, it could end up wreaking havoc on an American city. One bright idea was to use a tether. Another was to conduct the test over the Pacific and, at the end, ditch the reactor into the ocean. Even in those earlier, happier days of the atomic age, it’s unlikely that government officials or American citizens would have approved of either.

Second, there was concern about opening Pandora’s box with the Soviets. A missile that could fly around for days dropping nuclear bombs and spreading radiation was sure to be destabilizing and to provoke the Soviets to develop their own version.

And that brings us back to today. The problems with a nuclear-powered missile are so numerous and obvious that some have questioned whether Putin is being hoodwinked by his scientists, or whether he is bluffing to scare the United States back into arms control agreements. In any case, what was once a terrible new idea is now just a terrible old idea.

No comments:

Post a Comment