Sudhanva Shetty

The government’s approval to sell 26% of the shares of India’s leading defence equipment manufacturer, BEML, to the private sector is will mark the first time in Indian history that the Ministry of Defence will lose control over one of its own companies (more here).

The government’s approval to sell 26% of the shares of India’s leading defence equipment manufacturer, BEML, to the private sector is will mark the first time in Indian history that the Ministry of Defence will lose control over one of its own companies (more here).

The government has also announced that similar strides will be made with ten other public sector companies. It says this is to increase profits, efficiency and to meet its deficit goal. However, critics have said that this is an effort of the government to allow back-door entry to corporates in the defence sector.

In light of recent developments, one might wonder about the consequences of having private defence manufacturers. India has nine public-sector defence manufacturers and most of its indigenous defence manufacturing belongs in the public sector, with the government. However, now, with the private sector poised to take a larger role in defence manufacturing, it will be apt to try to understand defence manufacturing around the world, and the consequences of privatising it.

There is a sizeable private presence in India’s defence sector already. That scenario is different from what we are talking about here – that is, the fate of BEML – which is ownership of defence companies by the private sector, where the government’s stake itself is a minority proportion.

By no means is the corporate-military nexus in India as corrupted as the same in the West. However, seeing as we are refusing to learn from their mistakes, we seem doomed to the same fate.

Defence manufacturing around the world

The arms industry or the defence industry is a global industry responsible for the manufacturing and sales of weapons and military technology. It consists of a commercial industry involved in the research and development, engineering, production, and servicing of military material, equipment, and facilities. Arms-producing companies produce arms for the armed forces of states and civilians.

Departments of government also operate in the arms industry, buying and selling weapons, munitions and other military items.

Many industrialised countries have a domestic arms industry to supply their own military forces. Some countries also have a substantial legal or illegal domestic trade in weapons for use by its citizens, primarily for self-defense, hunting or sporting purposes. Illegal trade in small arms occurs in many countries and regions affected by political instability. (The Small Arms Surveyestimates that 875 million small arms circulate worldwide, produced by more than 1,000 companies from nearly 100 countries.)

The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) estimated in 2012 that military expenditures were roughly $1.8 trillion. This represents a relative decline from 1990 when military expenditures made up 4% of world GDP. Part of the money goes to the procurement of military hardware and services from the military industry.

The five biggest exporters in 2010–2014 were the United States, Russia, China, Germany and France, and the five biggest importers were India, Saudi Arabia, China, the United Arab Emirates and Pakistan.

Privatisation of defence

As mentioned above, many industrialised countries have a domestic arms industry to supply their own military forces. Contracts to supply a given country’s military are awarded by governments, making arms contracts of substantial political importance. Various corporations bid for these contracts, which are often worth many billions of dollars.

As mentioned above, many industrialised countries have a domestic arms industry to supply their own military forces. Contracts to supply a given country’s military are awarded by governments, making arms contracts of substantial political importance. Various corporations bid for these contracts, which are often worth many billions of dollars.

The end of the Cold War left the defence industry at a major turning point. During the Cold War, countries maintained their own defence industries, constantly ready to respond to threats. And nations knew where the threat was likely to arise – the Cold War period offered that kind of certainty. This helped both defence planners and defence companies, ensuring a thriving nexus between defence corporations, the military, and the government.

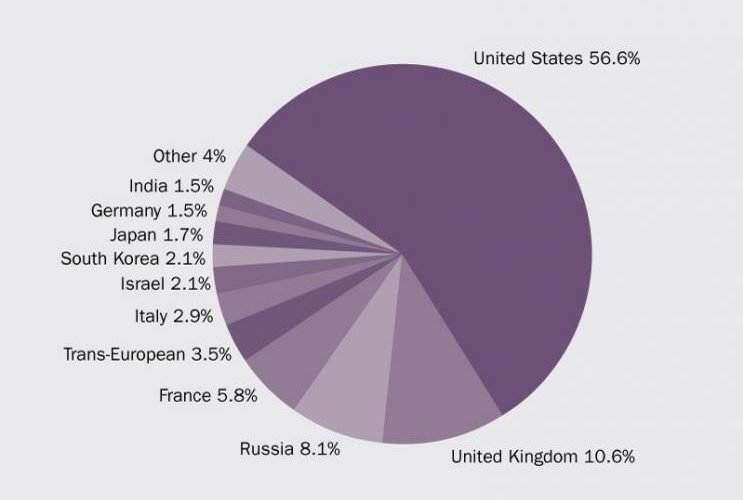

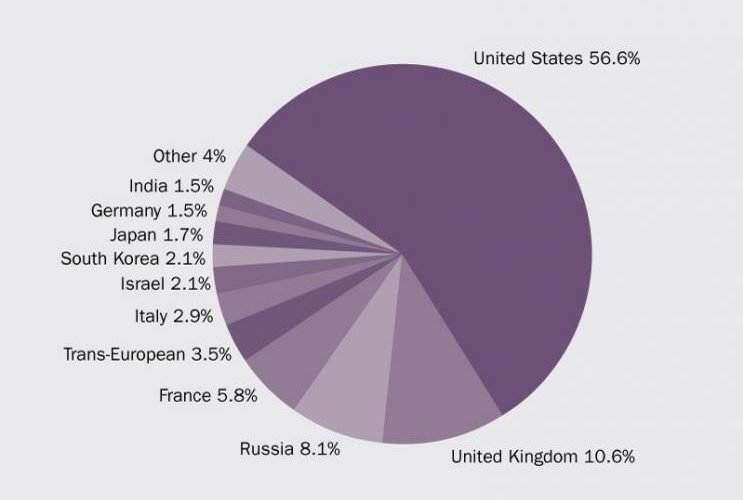

However, after the Cold War, the world looked very different. Defence spending fell by about a third between 1989 and 1996. 24 of the 100 largest defence companies in 1990 had left the industry by 1998. Those that remained grew larger through a series of consolidating mergers. A more collaborative international security community appeared to be emerging to respond to what were largely regional outbreaks of war. The defence industry was by no means obliterated, but it reinvented itself to accommodate to an environment that had transitioned from a state of omnipresent war to one of regional warfare. Share of arms sales of companies, by country.

Share of arms sales of companies, by country.

Share of arms sales of companies, by country.

Share of arms sales of companies, by country.

The military-industrial complex

The military-industrial complex (MIC) is a phrase coined by former US President Dwight Eisenhower to denote the growing nexus between defence manufacturers and a nation’s military. Over the years, it has been rephrased to “military-industrial-congressional complex” to add the influence MIC has on politics. In some countries, this three-sided relationship is called the Iron Triangle.

The term was coined by Eisenhower, who dedicated his last address as President to warn the American people about the growing dangers of the MIC. In his 1961 speech (full text here), Eisenhower famously said:

“Our military organisation today bears little relation to that known by any of my predecessors in peacetime, or indeed by the fighting men of World War II or Korea.

Until the latest of our world conflicts, the United States had no armaments industry. American makers of plowshares could, with time and as required, make swords as well. But now we can no longer risk emergency improvisation of national defense; we have been compelled to create a permanent armaments industry of vast proportions. Added to this, three and a half million men and women are directly engaged in the defense establishment. We annually spend on military security more than the net income of all United States corporations.

This conjunction of an immense military establishment and a large arms industry is new in the American experience. The total influence – economic, political, even spiritual – is felt in every city, every State house, every office of the Federal government. We recognise the imperative need for this development. Yet we must not fail to comprehend its grave implications. Our toil, resources and livelihood are all involved; so is the very structure of our society.”

The military-industrial complex was born during Europe’s Industrial Revolution. It gained traction in the years between the two World Wars, fuelled by regional conflicts and increasing defence spending. MIC became part and parcel of the political establishment and popular debate during the Cold War years.

How the military-industrial complex corrupts democracy

To understand the devastating implications of the military-industrial complex, let us take a look at the MIC’s impact in the United States. The United States is by no means the only country swamped by a MIC – in fact, 75 of the top 100 arms-producing companies are located outside the US. However, these non-US companies had a combined sales total of $209.8 billion (2013) while the 25 US companies had a combined sales $245.3 billion. The United States has the world’s most active MIC; and, as the world’s largest defence manufacturer, defence exporter, and defence spender, America’s MIC is also the most devastating.

America’s military-industrial complex contributes heavily to American politicians – essentially, members of the US Congress. The defence sector includes laboratories, universities, and various weapon, aerospace, and electronics companies.

According to the Center for Responsive Politics, individuals and political action committees associated with the defence sector contributed $150.8 million to political candidates and committees in the past two decades. While Republican candidates are favoured by the MIC, ultimately contributions are made to whoever is in power.

The Center for Responsive Politics states that the defence sector also has a formidable federal lobbying presence: in 2009, more than 1100 lobbyists represented nearly 400 clients. The amount spent on defence lobbying and the number of lobbyists have steadily increased during the last two decades. An illustration of how the MIC interferes in governance.

An illustration of how the MIC interferes in governance.

An illustration of how the MIC interferes in governance.

An illustration of how the MIC interferes in governance.

Defence corporations are private entities, not elected representatives, and they have massive amounts of money, influence, and clout. The nexus of the political, military and corporate elite is democratically damaging, corrupt, and unethical. This intertwining of investments – “which requires always-expanding growth to survive” – is not difficult to eradicate, it is also difficult to challenge. It is also a hindrance to any grassroots peace process, as it relentlessly advocates for military expansion. For the MIC, war is literally profit.

To the chagrin of activists, the MIC is a system that grows ever more consequential while remaining largely invisible even to those who are charged with overseeing it. As Barrett Brown ominously noted:

“Even most members of Congress are unaware of the extent to which both the military and intelligence community have come to depend on private contractors to provide the software and ingenuity necessary for both conventional and information warfare in the 21st century.”

Another serious consequence of the MIC is that it campaigns actively and effectively against arms control and disarmament. Additionally, other than interfering in legislative procedures, it exerts a controlling influence on the shaping of foreign policy of that nation. Those who traffic in military procurement have a vested interest in an unstable international environment. These are the modern “merchants of death” who are busy pursuing their own interests in complete disregard of humanitarian considerations or human rights. Lockheed Martin is the largest arms-manufacturing company in the world.

Lockheed Martin is the largest arms-manufacturing company in the world.

Lockheed Martin is the largest arms-manufacturing company in the world.

Lockheed Martin is the largest arms-manufacturing company in the world.

Privatisation of defence – we know it’s a bad idea

The Government of India has been committed to expanding the scope of its indigenous arms industry. It wants to decrease exports, built its reputation as a self-sufficient arms manufacturer, and use the profits in other sectors like infrastructure and education.

However, despite its best efforts, India has made uninspiring progress when it comes to indigenous defence manufacturing. The Government is well aware of the private sector being a vibrant and dynamic force, and it seems to have come to the conclusion that its military prowess will remain untapped if it continued to bank on public sector alone. However, selling most of its stakes in defence manufacturing companies is not the way to go about this.

For the complex between defence manufacturers and the political and military establishment, conflicts are a routine fact of life. It lobbies the government to spend hundreds of billions of dollars every year, and it feasts on these riches – while the world suffers in a state of perpetual war and suffering. And almost nothing is ever done about it.

Allowing the private sector to control the defence sector has altered political dynamics around the world – but particularly in the West. It has led to the rise of corporate cronyism, allowing unelected, rich business tycoons to have an unwarranted say in the foreign policy of a nation. In too many cases, these corporate leaders have too much say in deciding which country their government would wage a war against, which country to issue sanctions against, which country to sell weapons to.

As Simon Jenkins wrote, today, it is not democracy that keeps Western nations at war, but “armies and the interests now massed behind them”.

We know this is a bad idea, we know its disastrous consequences. However, instead of learning from history, instead of learning from other countries’ mistakes, why are we so foolish as to repeat their mistakes?

Let us go back to Eisenhower’s prophetic 1961 speech. He said that the potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist – and, to combat the creeping influence of the military-industrial complex, citizens must remain forever alert and passionate to ensure their military’s incorruptibility and their government’s accountability.

No comments:

Post a Comment