By Niklas Masuhr for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

When Russian intervention forces occupied the Crimean peninsula in February 2014 in a coup de main, NATO was still committed in Afghanistan. After more than ten years of counterinsurgency and stabilization operations, the crisis in Ukraine triggered a reorientation towards its original purposes of defense and deterrence. During the same year, at the NATO summit in Wales, it was decided to enhance the speed and capability with which NATO forces could respond to a crisis. The subsequent Warsaw summit in 2016 added rotating multinational contingents in its eastern member states in order to signal the entire alliance’s commitment to their defense. Below these adaptations at the level of NATO, national armed forces are being reformed and rearranged because of the shift in threat perception. This analysis focuses on the military forces of the United States, the United Kingdom and Germany. The tactics and capabilities Russia has brought to bear in eastern Ukraine in particular serve as the benchmark according to which these Western forces are being shaped.

US Army paratroopers during NATO exercise Swift Response on Adazi military ground, Latvia, June 9, 2018. Ints Kalnins / Reuters

Russian Warfare

At first glance, stabilization missions such as those in Iraq and Afghanistan appear to be more complex tasks for militaries to execute than conventional combat against foreign peers. However, a revived Russian military is posing fundamental challenges to NATO and its members, as it has been deliberately designed to offset Western strengths and to capitalize on NATO’s weaknesses since 2008. One major element of these “New Look” reforms was technological; in particular, a focus on highly modern standoff weapons such as long-range cruise missiles, anti-ship and anti-air missiles, and equipment designed to disrupt enemy radio and satellite communications. While Western forces enjoyed unimpeded air superiority and secure communications in Iraq and Afghanistan, neither could be counted on in a potential clash with Russian troops, significantly increasing the risk of casualties.

At first glance, stabilization missions such as those in Iraq and Afghanistan appear to be more complex tasks for militaries to execute than conventional combat against foreign peers. However, a revived Russian military is posing fundamental challenges to NATO and its members, as it has been deliberately designed to offset Western strengths and to capitalize on NATO’s weaknesses since 2008. One major element of these “New Look” reforms was technological; in particular, a focus on highly modern standoff weapons such as long-range cruise missiles, anti-ship and anti-air missiles, and equipment designed to disrupt enemy radio and satellite communications. While Western forces enjoyed unimpeded air superiority and secure communications in Iraq and Afghanistan, neither could be counted on in a potential clash with Russian troops, significantly increasing the risk of casualties.

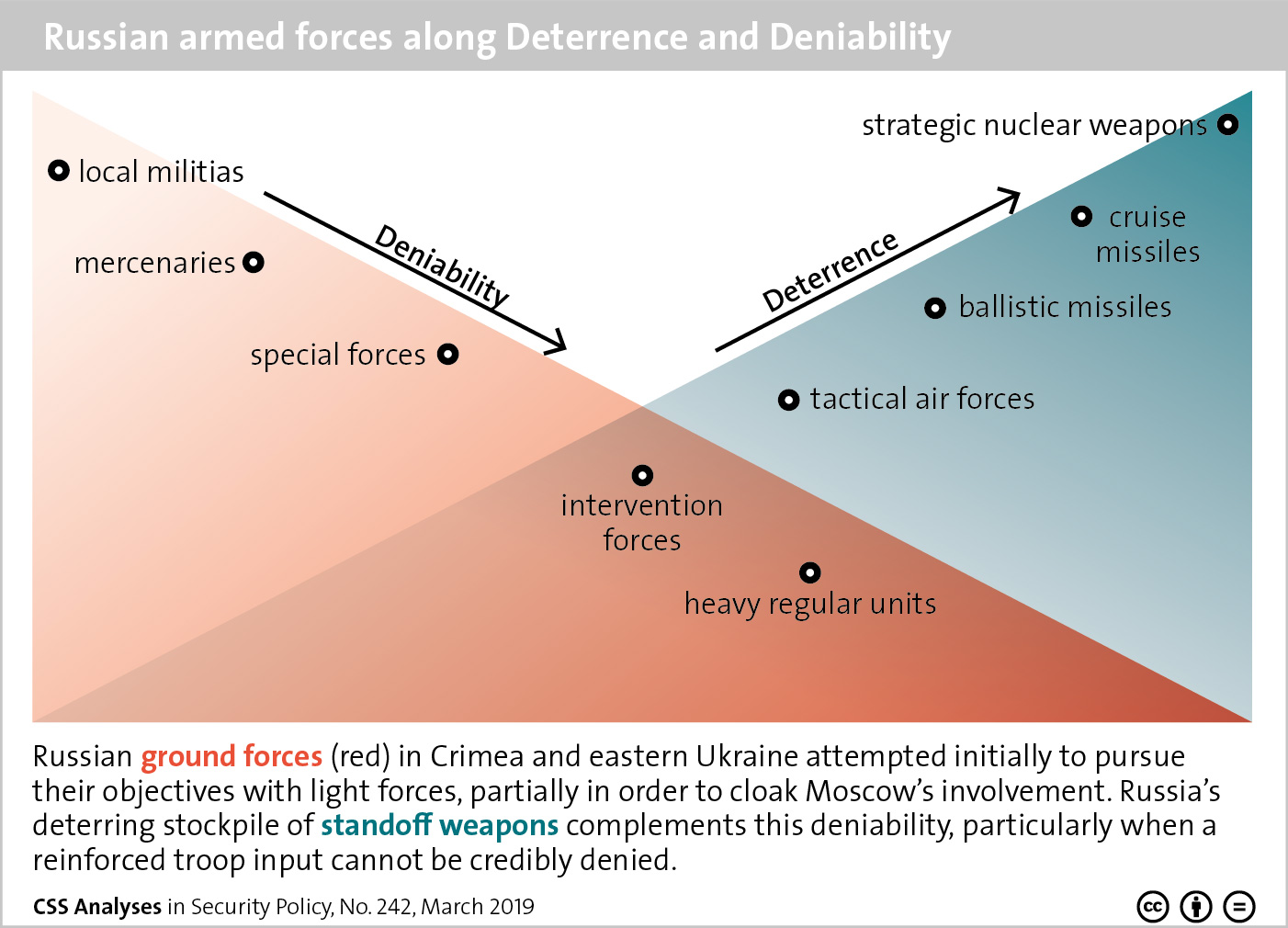

During Russian operations that led to the occupation of Crimea and the escalation in Donbass, respectively, the government obscured and denied the involvement of its troops. The Kremlin touted units deployed to Crimea as “local resistance fighters”, and entire army formations supposedly consisted of “volunteers currently on vacation”. In reality, Russia pursued its objectives in both theaters through a combination of local sympathizers and Russian troops that at least initially consisted of low-footprint special operations and expeditionary forces without insignia to keep the narrative of local resistance alive as long as possible. Apart from this focus on deniability and ambiguity, the coup de main in Crimea and later Russian operations in the Donbass have little in common. The Crimean operation in particular, carried out by light expeditionary forces, is a unique case since its success was in part enabled by a local population that largely viewed the existing Russian naval base at Sevastopol as legitimate.

However, in eastern Ukraine, a similar approach resting on a minimal Russian presence was markedly less successful, as separatist militias were driven back by the Ukrainian army despite being supplied with weapons from Russia. In order to salvage the military situation, Russian armed forces conducted two large-scale offensives in August 2014 and January 2015 involving thousands of troops, which enabled Moscow to negotiate favorable ceasefire agreements at Minsk. In combat, these troops primarily used massive artillery fire to destroy Ukrainian units from afar. Separatist militias were deployed as screening forces to reduce casualties among Russian regulars and to spot and identify targets for the artillery. Additionally, Russian forces were equipped with anti-air systems and sophisticated electronic warfare equipment in order to keep the Ukrainian air force at bay. The core of Russian regulars was only used in combat against significant Ukrainian targets using traditional equipment such as main battle tanks, as well as modern communications and reconnaissance drones.

Besides its ground forces, the modernized Russian military is equipped with standoff weapons such as ballistic missiles and air-and sea-launched cruise missiles – not to mention Moscow’s large arsenal of strategic nuclear weapons. These long-range systems explicitly serve to deter a local conflict from escalating at Moscow’s expense, for example via a Western military intervention. As such, they allow Russian forces to be deployed with a low footprint, primarily relying on local proxies, special operations forces, or private contractors while reinforcing the appearance of a local resistance movement – as opposed to an outside military intervention.

It should be noted, however, that the Russian interventions in South Ossetia, Ukraine, and Syria have been, and continue to be, executed in vastly different contexts with distinctly identifiable approaches. Accordingly, it is not possible to codify Russian military action in a “playbook”, as is often assumed. Similarly, conceptual pillars of contemporary Russian warfare revolve around traditional arguments put forth by Soviet military theorists, even if in recent history the emphasis has been placed more on non-military and unconventional means. As such, the often implied image of a ‘new Russian way of war’ does not hold up.

US Land Forces

The US Army has undergone several significant transformations in recent years, each designed to focus the force on a particular challenge in line with national security priorities. The last of these transformations was the attempt spearheaded by prominent generals, such as David Petraeus, to rearrange the Army’s structure and doctrine in order to conduct counter-insurgency, stabilization, and counter-terrorism operations. However, with the Russian military returning to the forefront of US threat perceptions, planners and thinkers have realized that old assumptions and dogmas are obsolete. Previous assumptions about how to fight a conventional war centered on the notion of US superiority in every relevant element of modern warfare, in particular through air superiority and assured real-time communications.

However, the recent Russian investments mentioned above have leveled the playing field, especially its anti-air weaponry, long-range artillery, and electronic warfare capabilities designed to jam US satellite and radio communications. US Army doctrinal documents since 2014 make this problem quite explicit. The main assessment is that Russia and China in particular have found a way of employing military force that offsets US superiority and capitalizes on flaws in the US logic of war. As such, Russian operations in Ukraine have obvious global implications for the Pentagon. The notion that a quick, surging military effort can defeat any adversary appears to have become a thing of the past. The reaction is a broadening of the conceptual sphere in which the US Army conducts operations. This means that next to the traditional domains of air, sea, and land, the new domains of outer space, cyberspace, and the electromagnetic spectrum are viewed as relevant domains in which to conduct warfare. The nascent doctrine designed to deter Russia and China in the future, Multi-Domain Operations, seeks to synchronize activities in all domains quicker and more effectively.

Additionally, the Pentagon expects future conflicts to be fought in a “grey zone”. This means a space between peace and war in which military means are deployed covertly and merge with intelligence and propaganda activity – as observed in Crimea and Donbass. In those crisis scenarios, premature or disproportionate military action on the part of Western forces risks a loss of public legitimacy and could serve as a justification for open (or at least less covert) Russian intervention. To be able to respond to such conditions, the US Army has established Security Force Assistance Brigades, consisting of experienced soldiers capable of training and advising friendly countries’ troops within their own borders. For one, this step intends to bolster the host military’s ability to resist encroachment or outright invasion – the Ukrainian army could be a potential candidate – without high material costs. On the other hand, the Army considers forward-deployed training missions to be an advantage if US or NATO troops are sent to reinforce the host nation in the event of a crisis. The assumption is that the training teams would already have forged links with the local military and population, which would enable reinforcing units to operate more easily in the relevant socio-political context – deemed a necessity in a “grey zone” context.

However, the escalation into conventional fighting seen in eastern Ukraine points to the risks associated with not preparing for this kind of warfare. Accordingly, the US Army has started to adapt its troops’ training and equipment in order to ensure superiority over Russian contingents. For example, Army troops are being trained to conceal themselves from drone-mounted modern sensors and to operate without real-time communications and navigation. In terms of equipment, the US land forces are primarily attempting to regenerate their artillery capabilities for effective suppression of any Russian counterpart, if necessary, and to bolster ground-to-air defenses. All these competencies had been consciously allowed to atrophy during the long period of counter-insurgency.

The example of the US is well suited to illustrate the dilemma in which Western forces have found themselves since 2014. An excessive focus on conventional military tasks invites the danger of losing political footing within an ambivalent or even hostile population if operations become necessary. Conversely, a population-centric focus carries the risk of a potential adversary escalating with traditional military means and creating facts on the ground. As such, all of NATO is faced with a difficult balancing act, being confronted with both “grey zone” and traditional military threats, as evidenced by British and German attempts at coping without a vast defense budget.

The UK: Flexibility as a Solution

The British military still finds itself in a period of regeneration following the 2010 defense budget cuts that were part of former prime minister David Cameron’s austerity policy. Since 2015, British national security and military planning documents have become more confident in tone, while certain core capabilities, such as carrier-based aviation, are being rebuilt (CSS Analysis Keohane No. 185, February 2016). Fiscal concerns, however, continue to play a decisive role for British defense, despite the deterioration of the security environment.

In its planning for a potential land conflict in Europe, the British military aims to be able to deploy a full division into Eastern Europe by 2025. As such, London’s plans are in line with a Europe-wide move towards organizing land forces in smaller brigades, which emphasize quick deployment, but in larger divisions. While brigades fit a threat perception that is dominated by regional crises and instability, they are not as suitable for traditional defense scenarios against a peer adversary. Next to the larger “mass” of divisions, Western armies tend to organize support capabilities, such as artillery, engineers, and air defense, at the division level – thus, multiple brigades share these units. Within this division, all capabilities deemed necessary are intended to be placed under one command to operate autonomously or – explicitly so – as part of a larger US corps or a multinational battlegroup. Specifically, the planned division is to consist of two heavy armored brigades equipped with tanks and two mobile “medium-heavy” Strike Brigades, equipped with newly procured systems. Especially a modular armored vehicle, Ajax, and modern armored personnel carriers. The emphasis on mobility can be explained by the relative lack of geographic flashpoints in the ongoing standoff between NATO and Russia – accordingly, combat units have to be able to react quickly and flexibly within a wide area. Additionally, the Russian military has proven that the combination of modern sensors and heavy artillery poses a great threat to stationary or cumbersome formations.

The British army’s changed priorities are reflected in its aspirations with regards to equipment and procurement. During operations in Afghanistan, the introduction of mine-resistant transport vehicles was fast-tracked; conversely, the focus is now on upgrading the Challenger main battle tank and Apache attack helicopter fleets. In the air, Eurofighter Typhoon jets have been modified with ground-attack capabilities. Apart from these equipment-related changes, British forces are stepping up training programs in the Norwegian arctic in order to assist in the defense of NATO’s northern flank. Royal Marines in particular are expected to reacquire arctic warfare skills after conducting more than ten years of counter-insurgency.

With regard to operating in a “grey zone” conflict, the British military has made two major adaptations. For one, a new unit (77 Brigade) was stood up that is designed to confront strategic propaganda, especially within digital media, and to conduct information operations itself. Additionally, the British army, much like the US Army, albeit on a smaller scale, concentrates the ability to train, advise, and assist foreign militaries overseas. These Specialised Infantry Battalions are thus designed to relieve the regular infantry of the burden of training missions in Africa, the Middle East, and Europe.

The Bundeswehr

Similar to its allies, Germany views the deterrence of Russian encroachment on eastern NATO states as the Bundeswehr’s primary task in the foreseeable future. In order to do so, the German Defense Ministry has announced several course changes with regards to increasing personnel and equipment after years of quantitative decline. Berlin has realized that previous cuts have hit the military’s conventional side particularly hard, which it now seeks to revive – even though stabilization missions are officially deemed of equal importance. As such, the army’s currently hollowed-out divisions are supposed to be reinforced incrementally, and ready to be fully fielded by 2032. In a first step, the Bundeswehr wants to contribute a fully staffed and equipped brigade to NATO’s Spearhead Force by 2023. However, these aspirations are contingent upon a significant and sustained increase in defense spending – which, as of early 2019, is anything but assured.

In addition to plans for increasing the size of the German armed forces, two innovative approaches stand out: Germany’s focus on NATO’s Framework Nations Concept (CSS Analysis Zapfe/Glatz No. 218, December 2017), and the creation of “mission packages” to give the forces more flexibility. The former concept describes the permanent integration of allied troops into German command structures. This authority does not extend, however, to automatic deployment decisions, which remain under the jurisdiction of national governments and parliaments. French troops placed under German command would not automatically be activated to conduct combat operations as part of the German unit. Accordingly, the main advantage of the concept lies in enabling allied national military forces to train with a much larger higher scope and scale than they could aspire to individually – and to practice skills required for conducting joint operations over long distances. For example, since being integrated into the Royal Dutch Marines, Germany’s naval infantry has had access to an amphibious warfare ship, a type of vessel the German navy does not have.

Secondly, the Bundeswehr views unit specialization for a specific type of mission, such as stabilization operations, as a luxury it cannot afford, instead opting for a single set of forces to conduct all relevant missions. For example, an infantry battalion is assumed to be capable both of conducting patrols in Mali and contributing to deterrence and defense in the Baltic states. In order to retain flexibility, mission packages are being created that will be attached to deployed units to contribute relevant experience and equipment without the unit itself having to be specialized.

Regarding the dimensions of procurement and equipment, the main aim is to regenerate previously cut capabilities. The German army is set to receive new artillery systems, including an increase in its munitions stockpile, as well as new infantry equipment. Additionally, the fleet of aging heavy transport helicopters is to be replaced by modern models. Another big-ticket defense project is the replacement of the Tornado aircraft and its ground-attack capability.

Financial and Cultural Divergence

Each of the three analyzed states is visibly attempting to leave behind it the era of counter-insurgency and to embark on modernization programs geared towards territorial defense, even though stabilization operations are still viewed as relevant tasks in strategic documents. Relevant capabilities are being rebuilt, whether they involve German or US artillery assets, the restructuring of the British Army, or investment in a thinned-out Bundeswehr. Doctrinal emphases tend to be similar, usually centered on improving reaction and deployment speed and preparing for modern “grey” conflicts in which civilian and military actors converge.

However, tangible differences can be detected – a vastly higher defense budget evidently gives the US Army the ability to conduct a much broader and deeper mental and material modernization than its European counterparts. As such, German and British military forces are both seeking to offset fiscal pressures by emphasizing the need for a flexible military instrument. On the British side, this can be seen in the army’s quest to deploy a medium-heavy division, whereas the German military banks heavily on its appeal as a framework nation and the added benefits of mission packages. Apart from those similarities, the British appear to be closer conceptually to their transatlantic “cousins” than the Germans are. The perceived blurring of traditional military domains (sea, air, land) with the information and social space is less pronounced in the German case. In addition, Berlin does not appear to view low-intensity attempts at subversion and encroachment into allied territory as a problem that should necessarily be confronted by military means.

No comments:

Post a Comment