By Jacob L. Shapiro

On Friday afternoon, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps seized two U.K.-affiliated oil tankers – the British-flagged Stena Impero and the British-owned Mesdar. After a couple of hours – and, according to Iran, a warning about environmental regulations – the Mesdar was released. The Stena Impero has not been so lucky. An IRGC statement on the Stena Impero said the ship had switched off its GPS system, was moving in the wrong direction in a shipping lane and had ignored repeated Iranian warnings. The statement stretches the bounds of credulity, considering that the Stena Impero was en route to Saudi Arabia and that maritime tracking data showed the ship making an abrupt change in course toward the Iranian island of Qeshm before its transponder was turned off at 4:29 p.m. U.K. time.

On Friday afternoon, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps seized two U.K.-affiliated oil tankers – the British-flagged Stena Impero and the British-owned Mesdar. After a couple of hours – and, according to Iran, a warning about environmental regulations – the Mesdar was released. The Stena Impero has not been so lucky. An IRGC statement on the Stena Impero said the ship had switched off its GPS system, was moving in the wrong direction in a shipping lane and had ignored repeated Iranian warnings. The statement stretches the bounds of credulity, considering that the Stena Impero was en route to Saudi Arabia and that maritime tracking data showed the ship making an abrupt change in course toward the Iranian island of Qeshm before its transponder was turned off at 4:29 p.m. U.K. time.

But a flexible sense of credulity is necessary in attempting to understand why Iran and the U.S., neither of which has an interest in fighting a war against the other, seem intent on hurtling down that path anyway.

According to Northern Marine, a subsidiary of the Stena Impero’s Swedish owner Stena AB, the Stena Impero’s sudden change in course was in response to a “hostile action.” The company said the ship was approached by unidentified small craft and a helicopter while in international waters. That does not square with the version of events offered by the IRGC, which claims the Stena Impero was violating international maritime law, or the head of Iran’s port authority, who was quoted by Tasnim News Agency as saying the Stena Impero was “causing problems” and was being routed to the Iranian port at Bandar Abbas.

However interesting Iran’s motivations and justifications may be, they ultimately do not matter a great deal; the reality is that Iran has seized a British-flagged ship in the Strait of Hormuz. This poses a double challenge to the United States, whose primary objective in the Middle East under the Trump administration has been to weaken Iran. By seizing a British-flagged ship (even if there were, as it appears, no British nationals aboard), Iran eschewed a direct confrontation with the U.S., preferring to confront a weaker U.S. ally. Indeed, Britain’s foreign secretary, while threatening “serious consequences” for Iran, also said the U.K. was not currently considering military options but was searching for a diplomatic solution to the situation. (The Telegraph reported that a British frigate, the HMS Montrose, had been dispatched to aid the Stena Impero but inconveniently arrived minutes late.)

A Severe Miscalculation

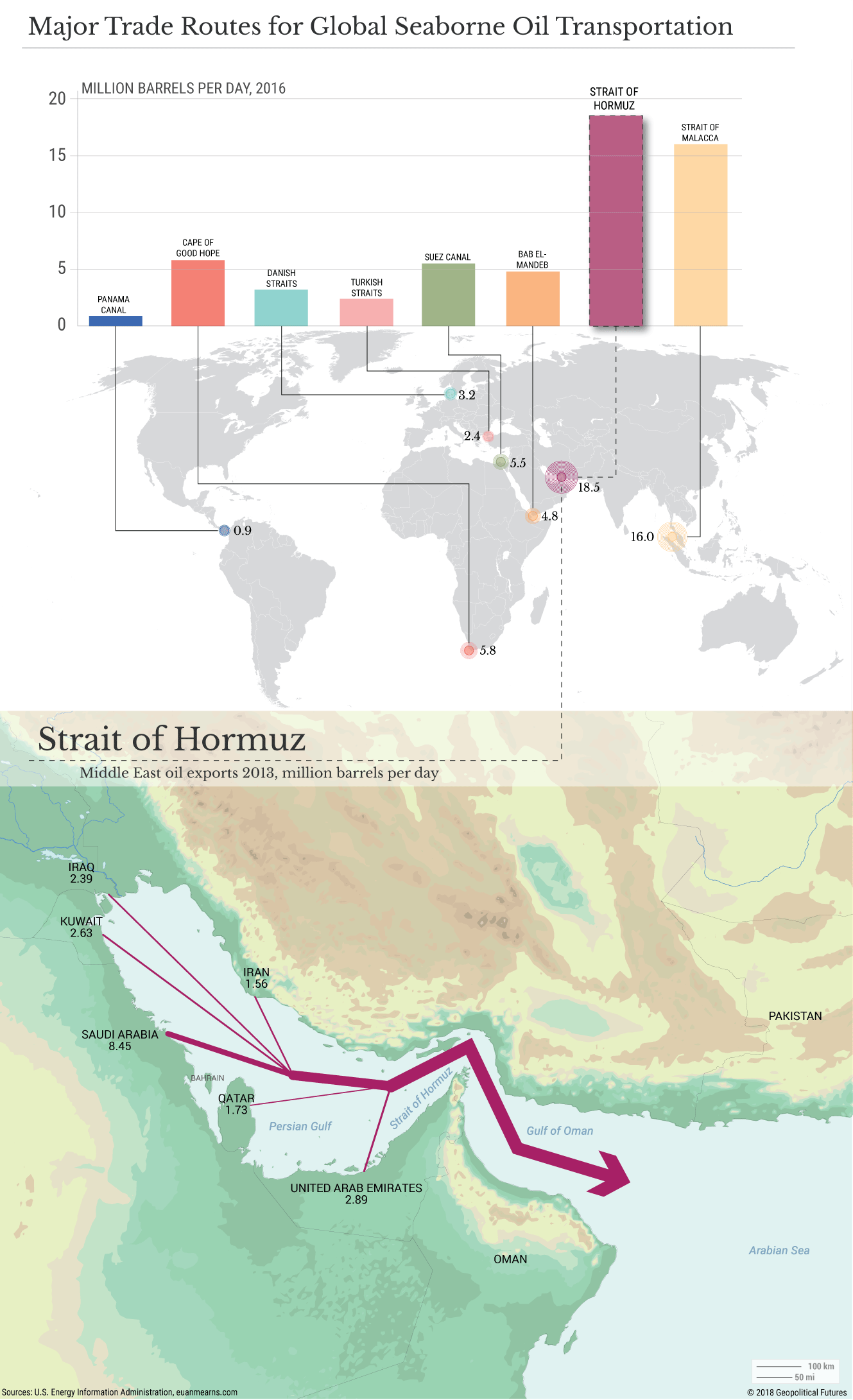

More broadly, however, Iran is attempting to show that it really can disrupt freedom of navigation in the Strait of Hormuz. Since 1945, the true global power and appeal of the United States have rested on its defense of the Strait of Hormuz. Iran has disrupted maritime traffic in the Persian Gulf in the past, most recently and notably in the late 1980s. But one critical thing has changed since then. Key U.S. allies depended heavily on oil from the Middle East in the 1980s; Turkey sourced 78 percent of its oil from the region, France 24 percent and the U.K. 10 percent. In 2018, those numbers were far lower – 7 percent, 4 percent and zero percent, respectively. With the exception of Japan, the countries most susceptible to the interruption of maritime traffic in the Strait of Hormuz are not countries the U.S. is as inclined to help – countries like India (which relies on the region for 50 percent of its oil), South Korea (62 percent) and, increasingly, China (21 percent).

As a result, this move is unlikely to have its intended effect. Tehran is desperately searching for leverage it can use to force the U.S. to ease the economic pressure on Iran. Breaking uranium enrichment restrictions laid out in the Iran nuclear deal has not done the trick, so now Iran is trying to show the U.S. and the world that, if it cannot catch a break, it will try to send the price of oil skyrocketing by blocking oil traffic out of the Persian Gulf. It is hard to characterize that as anything besides a severe miscalculation by Tehran. The U.S., especially under the current administration, will not feel pressured to ease up just because Iran has seized a ship or two. If anything, Washington will use that as justification for a much more aggressive approach to safeguarding maritime traffic in and out of the Strait of Hormuz, even if that benefits a country like China. The guarantor of freedom of maritime navigation isn’t much of a guarantor if it decides to pick favorites at a time like this.

At the end of the day, Iran simply cannot shut down maritime traffic through the Strait of Hormuz. It is trying to stoke fears that it is capable of doing so, but ultimately, Iran can’t keep the strait closed for any considerable length of time.

There is one more scenario to consider, which is that the Iranian government may be losing its monopoly on force in the Islamic Republic. Truth be told, the very existence of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, which is charged with defending not the state but the spirit of the revolution, has always meant that power in Iran does not lie solely with the Iranian government. But this particular Iranian government staked its legitimacy and its hopes for Iran’s future on the windfall it expected to flow from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action. Not only has the windfall failed to materialize – Iran’s economic situation is just as bad if not worse than at any time preceding the JCPOA. The Iranian government may not be calling the shots here. The IRGC may very well be taking things into its own hands, or, at the very least, providing cover for fed-up local officers or commanders tired of Iran’s inability to push back against the United States. It is also possible that the Iranian government likes the good cop-bad cop routine that the IRGC allows it to play. The opacity of Iran’s domestic politics right now makes it very difficult to know exactly how Iranian decision-makers are thinking about its grand strategy.

Unintended Consequences

As we have said before, the two countries with the least interest in a U.S.-Iran war happen to be the United States and Iran. But interests don’t always define how these sorts of situations play out. Consider that the United States announced this week that it was deploying 500 troops to an air base in Saudi Arabia to beef up its air defense systems. It was the presence of U.S. troops in Saudi Arabia after the first Gulf War in the early 1990s that sparked a rage so deep in a man named Osama bin Laden that he formed a group called al-Qaida, which attacked the U.S. and drew it into the Muslim world. In a sense, even that small and seemingly innocuous deployment set off a chain reaction that eventually resulted in the U.S. destruction of Iraq and, with it, the natural barrier to Iran’s expansion in the region.

The unintended consequences of these kinds of contingent events are always hard, if not impossible, to divine. The most likely scenario is that, like other recent activity in the Persian Gulf (the U.S. shooting down Iranian drones, Emirati tankers disappearing without a trace, mysterious mines being placed in broad daylight on Japanese oil tankers in the Strait of Hormuz), this incident will also be resolved. The U.S. will be content with maritime traffic continuing unimpeded and the Stena Impero set free, while Iran will be content with having made its point. Still, every time something like this happens, the risk of a wider conflagration rises – because that risk is defined not by broad historical forces but by the decisions and emotions of the sailors, airmen and soldiers involved. And who knows what future unintended consequence an event that will soon be old news might portend down the road.

For now, all we can do is wait and see whether and how quickly Iran will realize it has miscalculated – and how far the U.S. determines it must go in responding. We hardly think a real conflict is imminent – everything strictly “geopolitical” about this suggests it isn’t. But the hard, realpolitik interests that should be at work here also didn’t suggest that we’d have gotten this close in the first place. Iran disrupting freedom of navigation in one of the most important chokepoints for one of the most important resources in the world is not something the United States is going to accept for very long – and that may ultimately be more important than any other factor here.

No comments:

Post a Comment