By Tenzin Dalha

The digital revolution has emerged as a key factor in the rapid dissemination of news and broadcasting views. Within the last decade, social media has replaced print media, signaling a paradigm shift in how we consume and convey information. Due to advances in science and technology, sharing news and information has become less time-consuming, more convenient, and more decentralized.

But many people don’t realize that convenience has cost them their privacy. As you flow through your daily routine on a smartphone, you inadvertently share more data than you realize. This trade off between convenience and privacy illuminates the case of WeChat with respect to Tibetans and the larger Tibetan issue. In my research, I have found that Tibetan netizens generally give up privacy for the sake of convenience when using WeChat, operated by the Chinese company Tencent.

WeChat, the world’s largest standalone messaging app, is constantly refining its technology to monitor — and censor — content from its more than 963 million monthly active users. But still, 70 percent of Tibetans in the diaspora use the application. Overseas Tibetans or anyone with family or relationships associated with Tibet tend to download the messaging app to stay in contact, since other global social media applications are banned in the region. Tibetans who want to communicate with their relatives have no other choice but to use this means of contact.

In the eight years since Tencent debuted WeChat, it has become the dominant social networking platform in China as a whole, including in Tibet. The app has grown into an internet behemoth with over 1 billion registered users worldwide and 902 million daily users. Last year, 45 billion messages were being sent on the platform every day, 18 percent more than in 2017. The reason behind this meteoric rise is the official ban on global social media platforms in China, aided both by censorship of foreign apps – WeChat’s competitors — and subsidies from the Chinese government. This also means that WeChat’s information technology services and software are fundamentally insecure. The Chinese government claims sweeping powers over any matter considered relevant to China’s national security and pressures Chinese firms not only to censor content but, when needed, hand over user data.

Yet for many Tibetans, mobile apps like WeChat have become indispensable in their social life. News and information spreads like wildfire on WeChat and Facebook feeds, even as the mainstream media struggles to catch up with the pace.

In an interview with Tibetans recently arrived in India, one woman told me, “WeChat is set to become more obligatory in the daily lives of many Tibetan people.” At the same time, there is scrutiny of WeChat, which has been linked to an alarming rise in arrests of Tibetans. That, combined with the implementation of the recent cybersecurity laws, makes many Tibetans practice self-censorship on WeChat: discussing more about social matters and reposting and forwarding messages that are nonpolitical.

This Tibetan told me that she realized her phone was tapped, and her calls and text messages were under surveillance. Before she left Tibet, the Internet Security Bureau surprised her with their ability to repeat her words and voice messages precisely when they called her in for interrogation.

WeChat in Exile

In every nook and corner of Tibetan communities in India, a large number of Tibetans are becoming addicted to Tencent apps, which they use extensively. People glued to their phone screens are a common sight, and many are sending voice or video messages, playing PubG, or using other functions to communicate.་ The popularity of WeChat stems from the ease of use, as well as the fact that voice messages do not require literacy in Tibetan. This means that Tibetans who may not be able to read Tibetan can still participate in groups and share their views and ideas confidently.

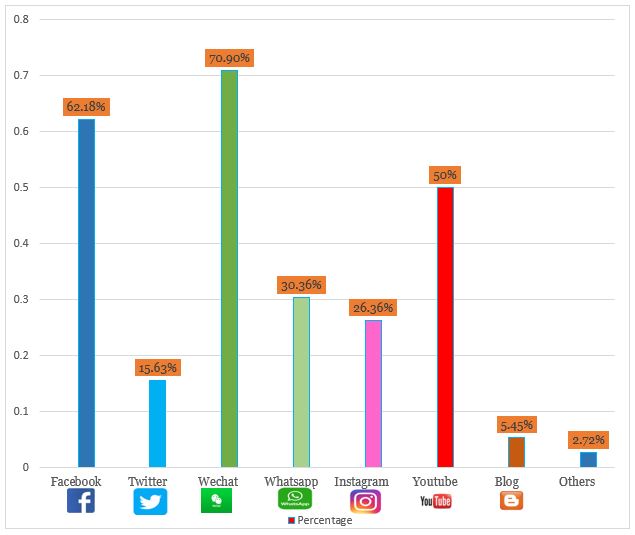

In a field survey with 550 participants from across India conducted by the author in 2018, 70.90 percent of Tibetans reported using the WeChat app extensively to connect with their family in Tibet, diaspora and abroad. And WeChat is reportedly only gaining popularity in Tibetan communities in exile.

Fig 1. The most popular social media platforms among Tibetans. Data from author field survey.

A Tibetan roadside vendor at McLodganj explains:

My parents are in Tibet and calls are expensive. Being deprived of formal education, I was introduced to a software called WeChat by my friend in 2012. I found it is just user friendly and does not necessarily require a fast internet connection and literacy. Since then I have been using this application. I can hold a button and talk to my family and relatives in any way at any time. I can get updates on many news and information. I even joined some chat groups and actively participated during the 2016 Tibetan election by airing my views.

But I strongly believe that I am under surveillance since the application is made in China. I rarely talk about and post any political related messages and images on my feed.

Another Tibetan man I spoke to explained to me how his family in Tibet would talk with him on WeChat almost daily. But surprisingly, one day he found that he had been removed from the family group chat, and that his parents had blocked him without any further explanation. He was notified that they were changing their profile pictures and status on WeChat, but was unable to send a message or get in touch with them thereafter. This incident has left him with questions — he assumes that the Chinese cyber police might have warned his family against contacting someone outside of Tibet.

WeChat and Beijing

Tencent has officially denied any government involvement in privacy matters several times. It is, however, an accepted reality that Chinese officials censor and monitor WeChat users. WeChat also states in its privacy policy that it may share users’ data with “government, public, regulatory, judicial and law enforcement bodies or authorities” to “comply with applicable laws and regulations.” On a technical level, thus, WeChat does not offer users much protection against government surveillance. Cases of Tibetans being arrested for circulating messages that have been deemed politically sensitive evince this.

As a company based in China, WeChat is subject to state laws on content control, and while WeChat claims to be end-to-end encrypted, there is a significant evidence to suggest that client-side censorship based on keyword and surveillance is prevalent, including erasing messages that are deemed politically sensitive issues.

One Tibetan girl, who went from Lhasa to study abroad in Europe, told me why she quit WeChat. When she was at home, she created a chat group and invited 30 of her classmates on it for a dinner party. Soon after, to her horror, she was called in by government officials for severe interrogation, and warned against creating any future chat groups for classmates. Later, out of frustration with the lack of privacy, she eventually quit WeChat. She further explains, “I felt insecure after the interrogation and became very cautious. I realized that the Chinese apps are absolutely not safe.”

The problem is larger than WeChat. In some villages in Tibet, police are taking away people’s phones and secretly installing an app that extracts data from emails, texts messages, and contacts. The surveillance app searches for information on a range of material, including literature by the Dalai Lama and messages that are deemed politically sensitive.

Tibet continues to witness a severe clampdown on WeChat, part of a broader crackdown on social media throughout China. Users face the threat of imprisonment if they are found responsible for “online rumors.” China has been cracking down hard on WeChat users who demonstrate sympathy and support for the Tibetan cause, and blocking any avenues for the spread of relevant information. Restrictions and fines have thus been on rise for sharing “illegal” content on WeChat.

In addition to the notorious firewall, the government can censor specific words to try and control the narrative of any given incident by pushing their own agenda and restricting citizens’ freedom of expression. However, many Tibetan and Chinese netizens use images and memes in particular to portray a serious topic in a lighthearted manner, and further increase the spread of information.

“Fake News”

The influx of information has led to a preponderance of news about conditions in Tibet. However, the catch is that false rumors are hard to tell apart from real news. Due to the security risks involved, it is difficult to validate news on Tibet, which primarily comes by way of social media.

The spread of “fake news” has become a global concern. False, misleading, or confusing online content created by fake accounts can harm the unity and harmony of any society. Unfortunately, lies and rumors are often taken seriously, and baseless allegations among Tibetans have the serious potential to affect the struggle to advocate the cause of Tibet.

Through my research, I found that some of the key factors behind growing paranoia and possible divisions in the Tibetan movement are lies and unverified rumors created by many fake accounts on popular social media outlets like WeChat and Facebook. These platforms raise concerns surrounding the dissemination of false or misleading information, as they lack the gatekeeping and verification processes that traditional media have. The convergence of traditional and new media as a means of information dissemination has raised questions regarding where to draw the line between regulation and censorship, and how to balance freedom of expression with inflammatory and provocative speech.

While enjoying the benefits of WeChat, we should be wary of the negative effects. In short, while WeChat has become and continues to be a popular medium for social interaction and bridging private and public lives, the safety of the application and security of shared content remains a legitimate concern for everyone.

Tenzin Dalha is a research fellow at the Tibet Policy Institute, doing research on Chinese cybersecurity policy and the social media landscape of Tibetan society.

No comments:

Post a Comment