by John Sjoholm

Democracies worldwide are facing critical challenges from ever expanding cyberwarfare operations with the ability to not just threaten infrastructure, but to control information. Until recently, it was generally accepted that there were just five countries that had the capability of carrying out offensive and defensive cyber-warfare operations on a large scale – the United States, China, Russia, Iran and Israel. But that list has grown. Lima Charlie News presents an in-depth guide to the major players and programs that have deployed to the world’s Cyber Battlefield.

Democracies worldwide are facing critical challenges from ever expanding cyberwarfare operations with the ability to not just threaten infrastructure, but to control information. Until recently, it was generally accepted that there were just five countries that had the capability of carrying out offensive and defensive cyber-warfare operations on a large scale – the United States, China, Russia, Iran and Israel. But that list has grown. Lima Charlie News presents an in-depth guide to the major players and programs that have deployed to the world’s Cyber Battlefield.

On November 2, 1988, Robert Tappan Morris, the 22 year old son of Robert H. Morris, Sr., launched what is considered the first computer worm to be distributed via the Internet. The Morris Worm, or Great Worm, once released slowed down infected systems to a crawl rendering the networks they ran unusable. Within hours, the Internet was largely disabled in North America, while the worm was making its way around the world. It would take nearly a week before the Internet was able to reconnect and become united again. Robert Tappan Morris would become the first person to be prosecuted and convicted under U.S. federal law for releasing the worm.

At the time, Morris’ father was the leader of an innovative new team at the National Security Agency (NSA). Morris Sr. would co-author a series of books for the U.S. Department of Defense and the NSA known as the “Rainbow Series”, computer security standards and guidelines that would help develop America’s earliest cyber warfare doctrines and tools.

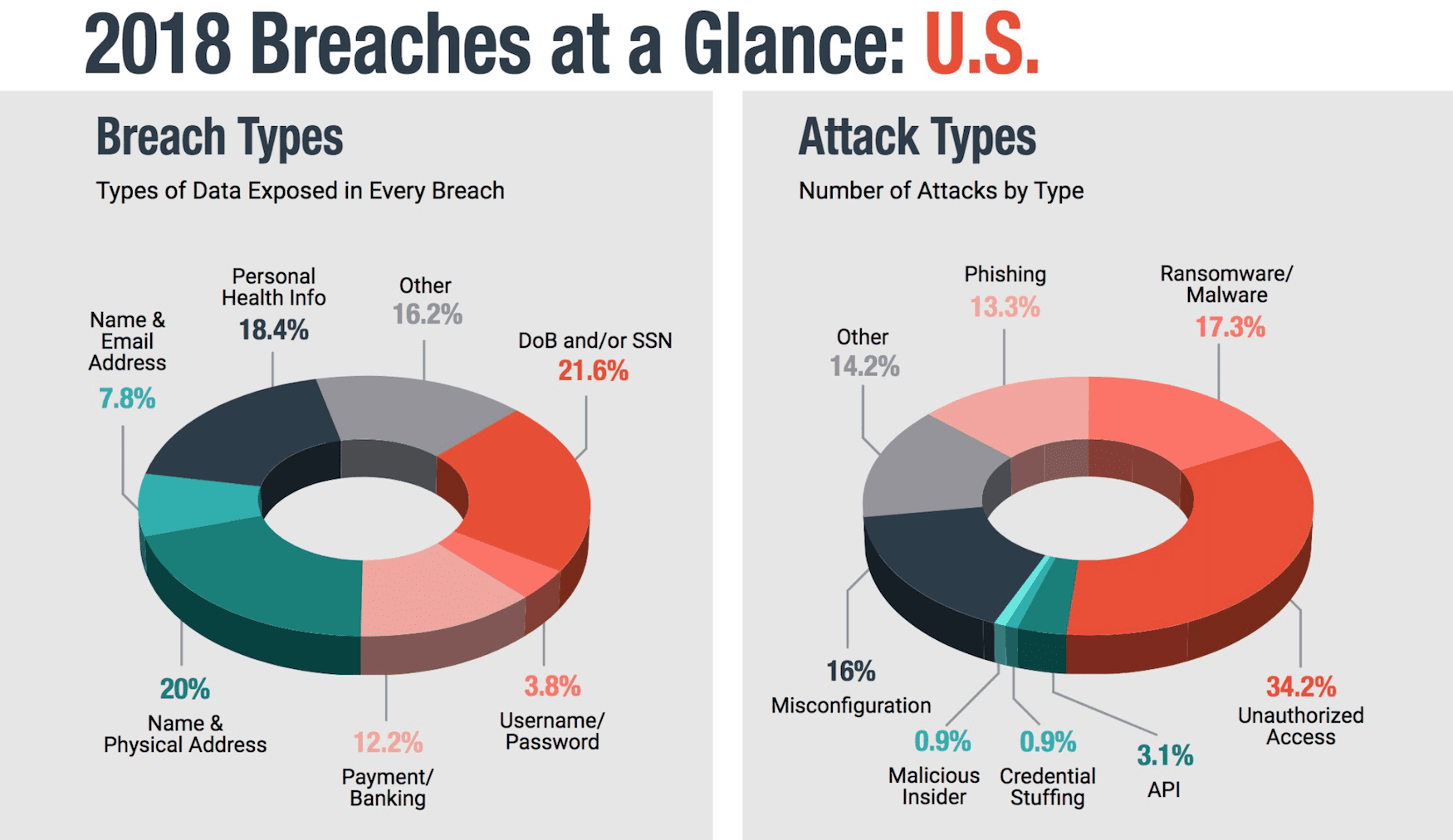

When Morris’ son released the Great Worm, it was a significantly different time. In 1989, there were just 27 known computer viruses. Today, that number is in the millions. The prevention of attacks and enforcement against violators has become an increasing quagmire costing billions. Cyber attacks against U.S. businesses cost $654 billion in 2018 alone. And while all network connections are to an extent traceable, this can only be taken so far before things get complicated. The Internet is essentially ruled by functional anarchy, and those wishing to control it will find that it is much like herding cats. Network traffic patterns, in combination with encrypted tunnels and anonymity servers, means that it is near impossible to control things on a good day.

Even worse, if you try to trace criminal traffic across world networks things will quickly become political. It has become even easier to hide an attacker’s true identity or intent by using proxies in nations that are less than cooperative with Western law enforcement agencies and counter-cyberterror efforts.

Attempts to trace an attack can be faltered with ease when traces require the cooperation of China, Iran or Russia. The refusal to assist with requests for data passing through their national networks leaves the case cold. It doesn’t help that attacks are often suspected of originating from state-sponsored or even state-operated outfits within those nations.

I do not know with what weapons World War III will be fought, but World War IV will be fought with sticks and stones.”

– Albert Einstein

The Great Worm to Cyber Warfare

Cyber warfare is an extremely cost-effective means of disrupting or disabling an opponent. With far less reliance on large-scale industrial capabilities, the new battlefield of the digital era relies on the availability of key individuals with particular skill sets and mental aptitudes. In this new domain, smaller, often poorly funded players can effectively strike much more powerful, well-funded foes.

This type of warfare also has additional advantages to traditional asymmetrical or even symmetrical warfare. It can be extremely difficult to trace an attack back to the originating attacker. While seldom of importance to small asymmetrical terror-oriented groups, like al Qaeda’s cyber warfare wing or the pro-Assad Syrian Electronic Army, that advantage is key to state-operated or state-sponsored groups seeking to mask their attacks.

A prime David vs. Goliath example is Palestine. Under the leadership of Iran-supported Hamas, Palestine is engaged in a protracted cyberwar with a significantly better-funded U.S.-supported Israel. Israel has in turn successfully attacked its other traditional foe, Iran, on multiple occasions with great success and accuracy utilising its cyber warfare capabilities.

The chief example of Israel’s offensive cyber warfare capability is the so-called Stuxnet computer worm attacks against the Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) systems of Iran’s nuclear program in 2010. It is believed that these attacks, which exploited a well-known vulnerability in Microsoft Word, were the breaching point of Stuxnet’s designers to propagate a larger, system and network-wide infection. The Stuxnet attack is widely believed to have employed a joint US-Israel designed cyberweapon that had begun development in 2005 with the specific objective of disabling Iran’s nuclear capabilities.

While Stuxnet appears to have been successful, the wide distribution of the worm led to other groups using it as part of their own cyber attack toolbox under a variety of deviations and names. This may include use by Iranian-backed groups.

Triton, believed to be a version of Stuxnet developed by an unknown third-party group, was deployed in December 2017 against an unidentified power station in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Triton breached the plant’s security measures utilising a very similar method as the original Stuxnet worm, and disabled the power station’s Triconex industrial safety technology (made by Schneider Electric SE). As a result of this attack, the power station’s personnel had to manually override the security systems and shut it down, causing a minor, largely localised disruption in the power grid.

While that attack was not serious, it was a good proof of concept. It would take until the end of 2015 before that proof-of-concept was deployed on a large scale.

[COURTESY OF FORGEROCK]In Ukraine, on December 23rd, 2015, the first known successful large scale cyber attack on a power grid took place. Utilising a trojan known as BlackEnergy, embedded into emails sent to publicly available corporate email addresses belonging to the Prykarpattyaoblenergo energy corporation, a group referred to as “Sandworm” was able to gain access to the corporate network.

[COURTESY OF FORGEROCK]In Ukraine, on December 23rd, 2015, the first known successful large scale cyber attack on a power grid took place. Utilising a trojan known as BlackEnergy, embedded into emails sent to publicly available corporate email addresses belonging to the Prykarpattyaoblenergo energy corporation, a group referred to as “Sandworm” was able to gain access to the corporate network.

As a result the group gained access to 30 substation SCADA controls which they used to switch the power off to 230,000 homes just before December 24th. With cyber conflicts having no rules of engagement to dictate even a modicum of humanity, thousands of households faced the bitter cold of a Ukrainian winter.

To cover their tracks, and to make bringing the stations back online even more difficult, the hard drives of several key computers were wiped out using the KillDisk malware. Whole segments of the internal IT-infrastructure were shut down. Service technicians would have to travel to each individual, often remote substation to reinstall or replace the control installations. It would take up to 6 hours before the systems were restored. Similar, but not yet successful attacks on the U.S.-power grid appear to be frequent.

As global cyber threats have continued to advance and expand in scope and complexity, within the past five years, Western nations have begun to wake up to the realisation that cyber activities from foreign operators can even endanger the very foundation of democracy. From the 5G network concerns with Chinese tech giant Huawei, to the ongoing discourse regarding aggressive Russian interference in American and European elections, the West has realised that safeguarding democratic values requires active engagement as much on the human terrain as on the cyber battlefield.

The Big Five of Cyberwarfare

In 2009 it was generally accepted that there were just five countries that had the capability of carrying out offensive and defensive cyber-warfare operations on a large scale: the United States, China, Russia, Iran and Israel. In 2019, ten years later, that list grew to include the United Kingdom, North Korea and Vietnam. The United Arab Emirates (UAE) is believed to be about to join the list as well. On a more tactical level, Syria, Lebanon and Germany are believed to be able to carry out targeted attacks.

The original five will for the foreseeable future continue to be the world’s primary cyber warfare actors.

USA (America First)

The United States of America is the oldest great cyber power with a strategic-level capability to not just carry out cyber attacks, but to defend against attacks on an open-war level. It is also one of the nations in the top five whose economy and social infrastructure are the most dependent on the Internet. Disruptions in the U.S. network could quickly prove devastating to all levels of its vital infrastructures.

As such, the U.S. has long prepared its offensive capabilities in a first-strike capable fashion, developing significant cyber capabilities. As far as defensive capabilities, the U.S. military and intelligence community quickly saw the need to divide the Internet – ARPANET for public use and MILNET for the relatively more closed off section.

However, the built-in defences implemented during the early days of the Internet were largely based on the notion of obfuscation rather than firm security measures. This approach was quickly proven to be inefficient, especially when even the so-called Morris Worm was able to make the jump from the public, academically oriented ARPANET, onto MILNET to infect systems.

This would lead to then-Vice Admiral John Poindexter suggesting in 1985 the introduction of a new security classification, “Sensitive but Unclassified” (SBU). The classification was intended to be implemented primarily on open academic research and fit below the usual levels of Top Secret, Secret and Confidential, while enabling the U.S. government to deny foreigners access to research on matters it perceived could be made sensitive if taken in a particular direction. One of the things Poindexter stated that would be labeled as SBU were research papers relating to what would become the Internet, and the U.S.-infrastructure of the networks which would come to encompass the Internet. The academic world rioted against the notion of being supervised by the cloak-and-dagger crowd. In the end, SBU would come into existence but it would only be applied, and then only sparsely, to research and related matters that were under explicit federal supervision and control. This was not at all near the grand scale that Poindexter had intended.

Throughout the 1990s, the U.S. worked to enhance its capabilities with the understanding that it would soon be forced to meet an enemy unknown on the cyber battlefield. However, the various agencies and units involved in these activities were largely held separate, with little overlap.

The CIA, which was quickly developing an impressive cyber offensive and espionage capability, did its thing separate from the NSA. The military would even divide its cybersecurity thinking and responsibilities to a regional, at times even localised, level under the control of base commanders. The Pentagon would, for a long time, merely advise bases on best practice rather than establish a common structure.

During this time, cyber attacks on U.S. military installations would be investigated by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), rather than the military intelligence division, despite the fact that the majority of attacks originated from inside Russia. The most famed such attack was the so-called Moonlight Maze attack in 1998, which managed to penetrate several sensitive U.S. government networks. That attack led to Newsweekreporting in September 1999 that the U.S. was “in the middle of a cyber war.” U.S. CYBER COMMAND COMPONENTS [IMAGE COURTESY OF THE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE / DOD NEWS]

U.S. CYBER COMMAND COMPONENTS [IMAGE COURTESY OF THE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE / DOD NEWS]

U.S. CYBER COMMAND COMPONENTS [IMAGE COURTESY OF THE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE / DOD NEWS]

U.S. CYBER COMMAND COMPONENTS [IMAGE COURTESY OF THE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE / DOD NEWS]

America’s Post 9/11 ‘Big Brother’

After the attacks on September 11, 2001, as the War on Terror began, it was apparent that the U.S. was in danger of being attacked by small non-state actors on a grand scale as well. Al Qaeda was attracting capable, often young people, with considerable knowledge of how to carry out cyber warfare and cyber terrorism as well as affiliated influence operations. At the same time, the threat from old and new state actor foes was emerging. Russia, China and Iran were all getting into the game with a vengeance.

This led to several controversial knee-jerk suggestions by the U.S. security community.

In early 2003, now-Admiral John Poindexter, the former National Security Adviser to the Reagan administration, and then-Director of the DARPA Information Awareness Office (IAO), suggested a large scale project called “Total Information Awareness” (TIA). This “Manhattan Project of Counter-Terrorism” would entail the constant automatic monitoring of all American citizens. This would enable the system, and its analysts to detect could-be persons of interest with the intent of anticipating and preventing criminal acts before they were even committed.

In 2003, the project was defunded by Congress, only to be renamed the “Terrorism Information Awareness” project. With a name like that, no one could refuse it. Yet certain changes had to be made to make the sale. In 2004, the Department of Defense (DoD) had it funded under a classified budget annex. The TIA project team members were transferred to the NSA which would supervise the new iteration of the project.

Now, the politicians argued, the purpose was to limit the project to only target military and foreign intelligence interests against non-U.S. citizens. This, of course, meant that the project would have to be even less privacy aware [1], as you can only know if a potential threat is of foreign origin after you have analysed it in detail. Since 2006, TIA has largely been operating as a classified in-house project at the NSA. Similar projects, such as Topsail and Basketball have also come under NSA umbrella.

Many of these projects, such as Topsail, were mainly developed on spec by the Science Applications International Corporation (SAIC) in Reston, Virginia, with the help of the IAO under the name Project Genoa II. The SAIC board has the retired Admiral Poindexter as an adviser. Its former head of technology, Deborah Lee James, served as the Secretary of the Air Force between December 2013 and January 2017. Mrs James has been a voice in favour of increased military-related expenditures and has named Russia as “the biggest threat” to U.S. national security.

In 2009, a joint task force designed to coordinate the U.S. cyber warfare activities and be the tip of the spear was created – United States Cyber Command (USCYBERCOM). The command is situated at Fort George G. Meade in Maryland. The base is shared with the NSA, among other similar outfits.

Iran (Not Your Father’s Persian Techno)

Cyber warfare has long been a part of Iran’s military strategy, and is considered a part of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) “soft war” operations. It is under this header that the support of foreign militia groups, and drop-in Islamist political parties, et al., can be found. Examples include Hezbollah in Lebanon, the al Houthi movement in Yemen, and Hamas in Palestine. All have their own cyber warfare operative units, often trained directly by experts from Tehran.

For instance, the Iranian Cyber Army, famed for its disruption of Twitter in 2009, is largely believed to be controlled by the IRGC. However, Iranappears less reliant on seemingly external, or named, groups than most of its contemporaries. Instead, Iran appears to prefer that the majority of its cyber operations exist under the direct command of the IRGC or one of its domestic national defence organs.

Israel has no doubt observed Iran’s growing offensive cyber capabilities with great concern.

In October 2013, the Iranian commander of the IRGC cyberwar division, General Mojtaba Ahmadi, was found dead in a wooded area near the town of Karaj, north-west of Tehran. Two 9mm rounds were lodged in his upper torso. The Tehran leadership immediately accused Israel’s external intelligence agency, the Mossad, of having carried out the killing.

Less than a week later, in mid-October 2013, the IRGC Brigadier General Mohammad Hossein Sepehr stated that Iran’s was the “fourth biggest cyber power among the world’s cyber armies.” The statement was agreed to by the civilian Israeli National Security Studies (INSS).

A July 2018 report by the American cybersecurity company FireEye detailed a suspected influence operation which originated from Iran. The operation aimed at individuals in the U.S., U.K, Latin America and the Middle East with the intent of leveraging a network of inauthentic news sites and supportive social media accounts to create anti-Saudi, anti-Israeli, pro-Iran and pro-Palestinian drive. Such behaviour was previously largely only attributed to Russian cyber influence and political warfare operations. A May 2019 New York Times article reported that despite FireEye’s 2018 report, these activities continued unhampered and with a degree of success.

Just last week, in the midst of escalated tensions over Iran’s downing of a U.S. drone, USCYBERCOM announced that it had engaged in a cyber offensive against an Iranian intelligence group believed to have assisted in the disabling of oil tankers near the Strait of Hormuz.

No comments:

Post a Comment