NGAIRE WOODS

The US-China trade and technology war has invited comparisons to the Cold War. For international organizations, the lesson of great-power rivalries is to focus on facilitating cooperation toward specifically defined goals, rather than attempting to establish new broad-based rules.

The US-China trade and technology war has invited comparisons to the Cold War. For international organizations, the lesson of great-power rivalries is to focus on facilitating cooperation toward specifically defined goals, rather than attempting to establish new broad-based rules.

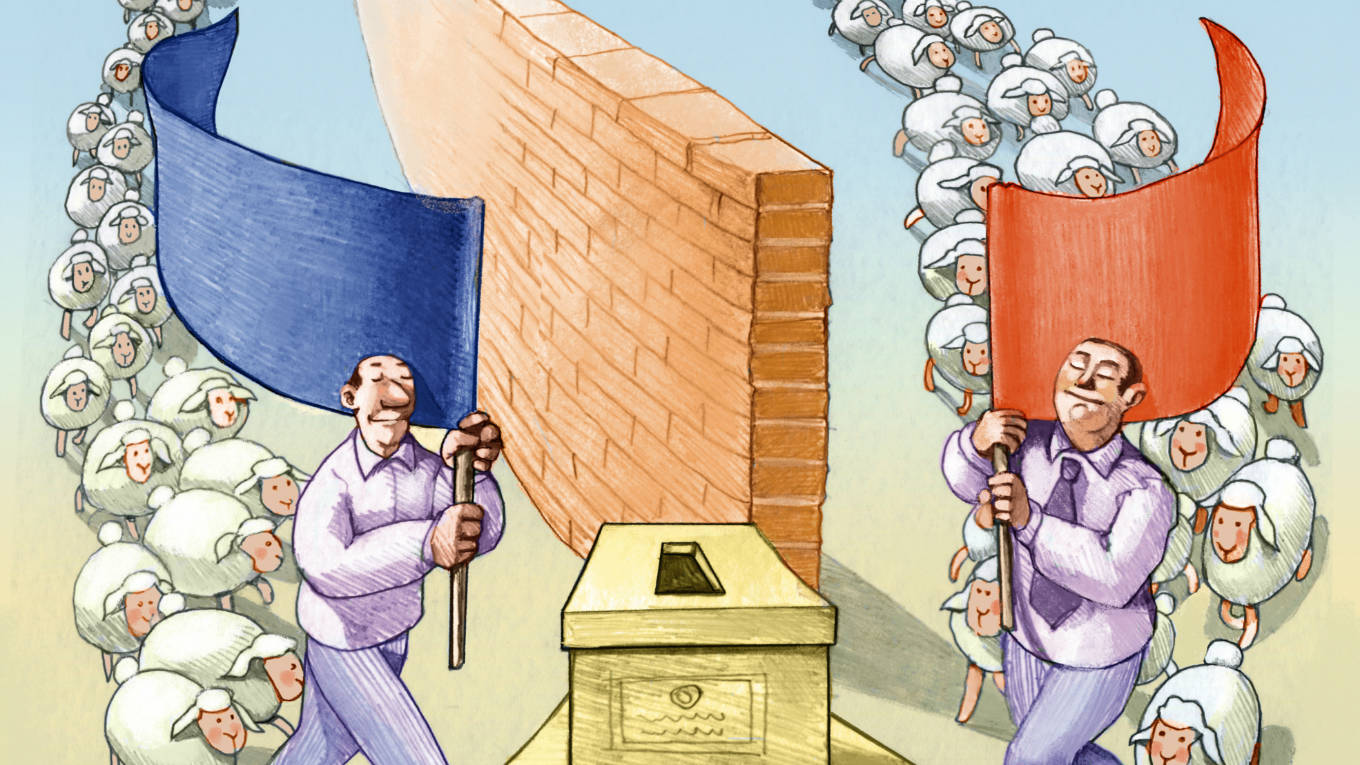

OXFORD – The strategic rivalry between the United States and China poses a sharp challenge to international organizations, which are now at risk of becoming mere pawns of either power. Whether multilateral institutions can retain a role in facilitating desperately needed international cooperation remains to be seen.

The Sino-American conflict is already replacing globally agreed rules with the exercise of raw power, as each side wrestles for access to resources and markets. The US is eschewing long-standing trade agreements in favor of unilaterally imposed measures. China is carving out its own economic and geostrategic sphere through bilateral partnerships and aid, trade, and investment packages under its transnational Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

The two rivals are also competing for control of new technologies and the data that enable them. Among the top 20 technology companies in the world, nine are Chinese and 11 are American. On the Chinese side, the tech giants enjoy access to a wealth of data, because they are backed by a government that is bent on collecting it for the purpose of surveillance and establishing a social-credit system. Equally, Chinese companies are expanding their reach and access to data, such as China’s CloudWalk deal to build facial-recognition software in Zimbabwe. On the US side, the tech giants are being supported through provisions in trade agreements like the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), which requires cross-border data flows without restriction.

The strategic rivalry is a battle not just for control over resources, access to markets, and technological domination, but also, more broadly, for control over the rules of the game. In 2015, when China created the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank as a new multilateral institution, the US refused to join and pressured others not to do so, either. Earlier this year, when China and the US disagreed over who would represent Venezuela at the IDB meeting (the US pressed China to accept a representative of the opposition to the government, and China refused), the institution’s Board in Washington, DC, canceled the meeting in Chengdu just one week before it was due to take place.

This is not the first time that a great-power rivalry has threatened to marginalize international institutions. After its founding in 1944, the World Bank was soon sidelined in the reconstruction of Europe. With the Cold War came heightened strategic competition in Europe, leading the US to pursue more direct means of engagement through the Marshall Plan. In the event, the World Bank was relegated to a different job: lending to poorer countries.

Some commentators describe the BRI as “China’s Marshall Plan.” Yet the new strategic rivalry differs from the Cold War in many ways, starting with the fact that the US and China are economically interdependent to a degree that the US and the Soviet Union never were. Still, the principle of “mutually assured destruction” created its own kind of interdependence, leading to cooperation on nuclear-arms control despite the intense rivalry.

One lesson of the Cold War may be particularly relevant today: attempts to establish broad rules, such as US President Richard Nixon and Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev’s Basic Principles Agreement in 1972, proved less effective than narrower arrangements such as the 1955 Austrian State Treaty conferring neutrality on Austria, or the 1962 agreement establishing Laotian neutrality. By the same token, formal multilateral treaties and organizations worked best when they addressed specific dangers, as in the case of the 1971 Berlin Quadripartite Agreement, the 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty, the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT), and the 1972 Incidents at Sea Agreement. All of these agreements were highly contested, but each played a role in managing the rivalry.

In the case of the Sino-American conflict, the challenge is to contain the trade war, which could have devastating consequences on other countries. Unfortunately, the current system of rules is already being eroded. The World Trade Organization’s dispute-settlement mechanism is being paralyzed by the Trump administration’s refusal to allow any appointments to its Appellate Body.

Breaking the impasse will require creative thinking and perhaps a series of narrower agreements to breathe life back into the system. For example, countries with trade disputes could make better use of the WTO’s 60-day bilateral consultations requirement to reach a settlement on their own. WTO leaders could be far bolder and more creative in finding ways to support rule-based trade. They should recall the way leaders in the United Nations initiated “peacekeeping” (which is not mentioned in the UN Charter) and expanded the use of the office of the Secretary-General to advance peace at the height of the Cold War.

Other multilateral organizations will also need to rethink their strategies. Regardless of whether larger powers are locking horns, the world desperately needs mechanisms to facilitate cooperation on issues such as climate change, biodiversity, cross-border infrastructure, and the regulation of new technologies. International organizations can provide a forum for debating such matters, sharing information, and arriving at common solutions. They can also play a crucial role as neutral monitors of previously agreed rules, reducing the temptation for any one country to cheat or pursue zero-sum, unilateral action.

China, the US, and the rest of the world have shared interests across a wide range of issues. But to facilitate cooperation toward common objectives, international organizations will need to be renovated. The World Bank, for example, could create new instruments to address regional and global challenges, instead of remaining locked into single-country loans, and it could shed the ideological baggage preventing some countries from embracing its Country Policy and Institutional Assessment approach. Rather than lending to poor countries in ways that amplify the biases of the world’s largest bilateral donors, the Bank should identify neglected areas and ensure balance in global development financing. It will also need to overhaul its governance structure to give both China and the US a sense of ownership and influence.

It is imperative that the Sino-American rivalry stops short of war. We know from history what can happen when national leaders define rivals as enemies and exploit national grievances for personal political gain. Right now, this tendency is on display in both China and the US.

To contain the new strategic competition, the rival powers, along with the rest of the world, should emulate the Cold War-era focus on narrowly defined, specific agreements rather than attempting to craft new broad-based rules. Multilateral organizations such as the WTO and the World Bank could play an important role in brokering such accords, but only if their respective leaderships are bold and creative, and if their stakeholder governments allow it.

No comments:

Post a Comment