by Abdolrasool Divsallar

On May 15, Iran announced that it would stop implementing some of its obligations under the 2015 nuclear deal (Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action or JCPOA) as a first response against U.S. sanctions. Additionally, the growing military threat against Iran is strengthening the military aspect of the Iranian government’s response. Beyond the current escalating tension between Iran and the U.S. that has grabbed so much media attention, Tehran is also considering longer-term military measures in response to U.S. pressure. Tehran believes that the Trump administration’s “maximum pressure” campaign could deepen the existing military expenditures disparity between Iran and its rivals and disrupt the regional military balance. It obscures Tehran’s military investments and increases the costs of implementing regional aspects of Iran’s deterrence capabilities. Trump sees “maximum pressure” as a way to restrain Iran’s power projection capacity to that of a “normal country“. However, Tehran fears that any future military imbalance could ignite a Saudi- or Israeli-led war even if that is not Trump’s intent. This is convincing Iranian leaders to adopt a new military doctrine.

On May 15, Iran announced that it would stop implementing some of its obligations under the 2015 nuclear deal (Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action or JCPOA) as a first response against U.S. sanctions. Additionally, the growing military threat against Iran is strengthening the military aspect of the Iranian government’s response. Beyond the current escalating tension between Iran and the U.S. that has grabbed so much media attention, Tehran is also considering longer-term military measures in response to U.S. pressure. Tehran believes that the Trump administration’s “maximum pressure” campaign could deepen the existing military expenditures disparity between Iran and its rivals and disrupt the regional military balance. It obscures Tehran’s military investments and increases the costs of implementing regional aspects of Iran’s deterrence capabilities. Trump sees “maximum pressure” as a way to restrain Iran’s power projection capacity to that of a “normal country“. However, Tehran fears that any future military imbalance could ignite a Saudi- or Israeli-led war even if that is not Trump’s intent. This is convincing Iranian leaders to adopt a new military doctrine.

Trump’s escalation is also shifting ordinary Iranians’ understanding of the threat. People are feeling an existential threat to the concept of “Iran” itself and not just to the “revolutionary state”. U.S. pressure has enabled staunch supporters of the Islamic Republic to conflate their “defending the revolution” discourse with a “defending Iran” discourse that has a wider appeal among ordinary Iranians. Despite huge social burdens, these developments are providing Iranian leaders with the backing needed to increase national resource mobilization for the military. Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei is convinced that the only solution to deter U.S. attack or future conflict is by responding to U.S. threats in kind. Indeed, he has emphasized that Iran will respond to threats with more threats. In other words, he believes that Iran needs to escalate the threat level against the U.S. in order to maintain effective deterrence. In practical terms, Tehran’s military response will probably be in a form of doctrinal review to balance the increasing threats. This means a shift from current second generation doctrine of “second strike” to the third generation doctrine of “massive retaliation”.

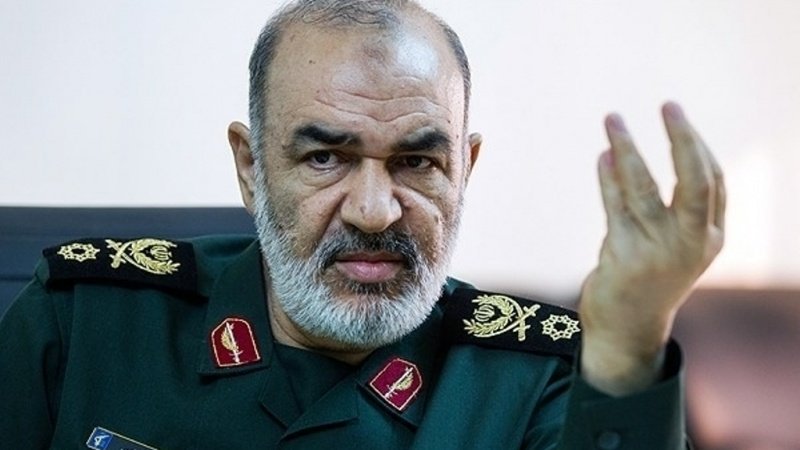

Against this backdrop, Ayatollah Khamenei has asked his newly-appointed Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) commander, Hossein Salami, to redefine the IRGC’s principal strategies. He has ordered Salami to provide complementary steps for the second phase of the Islamic Revolution. The mission of the second phase emphasizes territorial integrity and asks for a broader regional and global role for the Islamic Republic. Indeed, the Supreme Leader has asked military officials to provide plans for extending Tehran’s reach to wider geographical zones. Salami, who is highly respectedwithin IRGC ranks and is seen as a strategic thinker, said at his inauguration ceremony on April 24 that the IRGC’s operations should be extended globally to make the “enemy” insecure to a larger extent. This concept became the foundation for a doctrinal review.

The first generation of Iranian military doctrine, “Effective Deterrence”, was developed during 2003-2010 using Iran’s internal vast geography to provide physical depth and erode an enemy invader. The doctrine was designed to increase any potential adversaries’ costs and to lower aggressors’ morale, in order to deter them from attacking. Various operational plans, including “mosaic defense“, were developed to do so. Meantime, Iran incorporated Anti-Access/Area Denial (A2/AD) capabilities to reinforce physical depth by hampering an enemy’s maneuverability and accessibility to its regional assets. However, this doctrine’s reliance on the war of attrition could have only provided deterrence against large campaigns, such as possible attacks by the U.S. or a U.S.-led coalition, which would eventually lead to a large-scale invasion of Iran.

In contrast, the second generation of Iranian military doctrine, developed through 2011-2014, was in response to emerging threats coming from the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, Israel, and ISIS. It no longer considered a U.S. invasion to be an imminent threat. The doctrine kept the defensive nature of the Iranian military, while second strikes relied on external strategic depth and firepower accommodated by Iran’s proxy networks and stand-off missiles. The secretary of Iran’s Supreme National Security Council, Rear Admiral Ali Shamkhani, admits that the value of a second strike is as a means of deterrence.

However, Trump’s maximum pressure is changing Iran’s threat assessments, leading to revisions in the Iranian military doctrine. Additionally, the second generation doctrine was developed before the current GCC-Israeli alliance had been forged. The emerging third generation doctrine is based on the idea that the limited second strike doctrine will not be able to deter attacks coming from the united alliance of the U.S., GCC, and Israel. Recent escalations are increasing the pace of these doctrinal adjustments.

The still-developing doctrine is characterized by an Iranian willingness to further expand the battle zone, while surprising the enemy with the intensity of offensive actions outside Iranian territories. On April 25, the chief spokesperson for the Iranian military announced that Iran will not follow a defensive strategy against a U.S. attack. The revision appears to be a shift from the current limited second strike doctrine to a “massive retaliation” doctrine.

Unlike the classic 1954 Dulles massive retaliation doctrine, Iran’s version is not based on nuclear capabilities. Instead, it will be likely based on two core concepts: expanding strategic depth by extending the geography of the war zone and surprising the enemy with the lethality of the battle space. The latter is achieved through massive firepower. With the new doctrine Iran wishes to take the initiative in defining battle space conditions and places, thus engaging adversaries in coercive war outside and inside its territories to inflict intolerable costs. This is clearly a turning point in Iran’s strategic thinking, as it merges the first generation concept of war of attrition with the second generation concept of external strategic depth.

Already, Iran has been successful in stretching its military footprint into Mediterranean ports. Now, it is willing to redefine its understanding of strategic depth to inflict global costs on adversaries further into the Red Sea and North Africa. Some observers believe that the current regional security context lends itself to such geographical expansion. Gen. Salami has always been in favor of strategic improvements in Iran’s missile program, to increase the lethality and range of Iran’s offensives. The latter is a critical element that changes both the scope and the quality of Iran’s method of warfare. Iran’s missile break-out time to operationalize missiles with a range greater than 2500 km could be shorter than what the U.S. anticipates. The operational requirements of the new doctrine include further improvements in hybrid warfare tactics, extended offensive A2/AD capabilities and a boost in firepower. Thus, Iran will take the initiative to improve both the offensive capacities and the geographical diversity of its proxies, while adding to the quantity, accuracy, and range of its missile stockpiles. This implies that Iran’s missile proliferation logic should change.

Contrary to its stated goals, the Trump administration’s “maximum pressure” campaign is pushing Tehran to more effectively use its military resources. Fear of losing deterrence capacity is forcing the country to shift its military doctrine to an offensive orientation. The U.S. already faces serious technological and operational unanswered challenges to a decisive victory in any war with Iran, while this new Iranian doctrinal adjustment will force the U.S. to fight in a much larger war zone with higher casualties than anticipated. Apart from its catastrophic regional consequences, this Iranian doctrine could consume major U.S. military assets indefinitely, strategically undermining U.S. global power projection capacity.

Dr. Abdolrasool Divsallar is a Rome-based independent scholar focused on Iranian defense doctrine, security policy and strategic thinking. He is a nonresident senior fellow at the Institute for Middle East Strategic Studies in Tehran. Previously he was a former research fellow at the Center for Strategic Studies of Expediency Council (2006-2012). He has published several books in Farsi, including Understanding Iran’s Military Environment (2007) and the Power of Information (2015). He has written for the Washington Quarterly, the International Spectator, Italian Review of Geopolitics (Limes), Russian Council on Foreign Relations and major Persian outlets.

No comments:

Post a Comment