By Xander Snyder

The U.S.-Iran standoff continues to evolve quickly, yet the blow-by-blow commentary covering tanker attacks, a downed drone, and reversed orders for airstrikes from the White House fails to consider the strategic logic behind an intervention, if in fact the Trump administration decides to intervene. With that in mind, it’s worth taking a moment to imagine what a war between the two would actually look like.

The U.S.-Iran standoff continues to evolve quickly, yet the blow-by-blow commentary covering tanker attacks, a downed drone, and reversed orders for airstrikes from the White House fails to consider the strategic logic behind an intervention, if in fact the Trump administration decides to intervene. With that in mind, it’s worth taking a moment to imagine what a war between the two would actually look like.

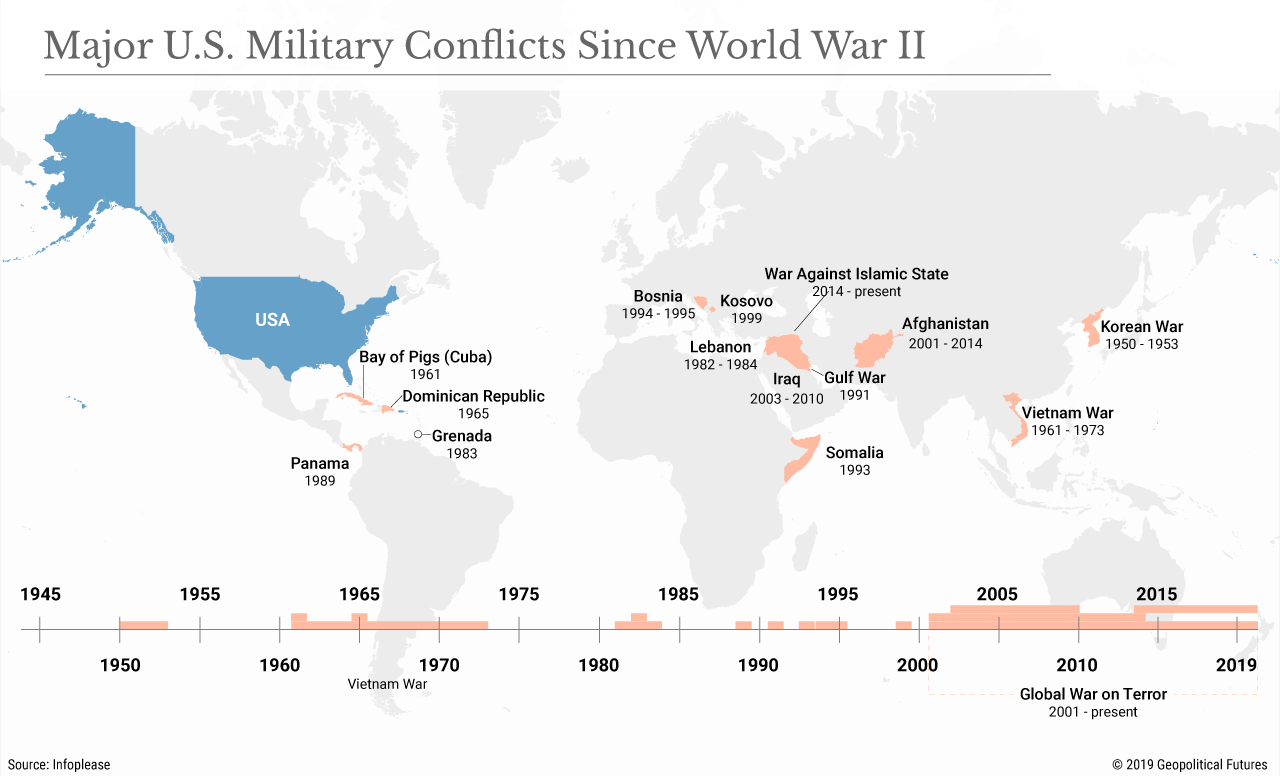

By now, the U.S. should have learned a thing or two from the Vietnam and Iraq wars. Distant foreign conflicts are difficult to win without a well-defined case for what success looks like and an overwhelming military commitment, the kind the American public is usually unwilling to provide unless faced with a massive and immediate threat. Small-scale engagements accomplish little and are instead more likely to evolve into larger conflicts. Installing foreign governments in the American image is more difficult, costly, time-consuming and even deadly than leaders are likely to claim. Backing a local proxy is often unpalatable for the country’s sense of ethics, but U.S. adversaries often have no such qualms. Those proxies are often an ineffective substitute for a U.S. military presence when it comes to pursuing U.S. objectives. And without a substantial, long-term commitment of U.S. forces, such wars are more likely to open a power vacuum when the U.S. withdraws. The result: a collapsed government, an invasion by a neighbor, a revolution that creates new and uncertain structures – or some combination of these. In fact, the U.S. has had few true victories in the wars it has fought since World War II.

Limited Airstrikes

Consider the U.S. government’s options, then, for a war with Iran. If the U.S. chooses a kinetic response, the first and most likely option would be a limited strike, similar in scale to or perhaps somewhat greater than the strikes on Syria that the Trump administration ordered on Syria in April 2017 and 2018. But Iran is not Syria. Iran has a sophisticated air defense infrastructure and plenty of air denial capability, increasing the chance of U.S. casualties. Further, a limited air strike probably wouldn’t accomplish anything meaningful. It might take out a handful of radar and air defense installations, sending a political signal but affecting in no real way the strategic reality on the ground. The only time U.S. air power alone has significantly shifted the reality on the ground was in Kosovo, but Iran today is far more powerful than Serbia in 1999.

Instead, a limited strike has a good chance of working against US interests. Iran’s economy is hurting, and its society appears more divided as citizens continue to grow frustrated with the government. The U.S. has deployed sanctions as a strategy to hobble the economy enough to create social pressure on Tehran, forcing the government to spend less on its defenses and its funding of militias in Syria and Iraq. And so far, they’ve been effective. If the U.S. sustained this tactic, over time Iran’s domestic situation would worsen, and its citizenry would be more likely to blame its leadership for their problems. And that would likely intensify the divisions within the government that are already emerging, resulting in either a more Western-friendly government or one dominated by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps.

Even limited U.S. airstrikes, however, would increase the probability of the IRGC consolidating power. Where sanctions may help create division, an attack would unite Iran’s hard-liners and reformers against the U.S. That unity would likely occur under the aegis of the hard-liners who have been warning all along that this day would come if Iran were foolish enough to trust the U.S. As the most powerful entity in the county, the IRGC would probably take over, and do so with popular support.

Use of Ground Force

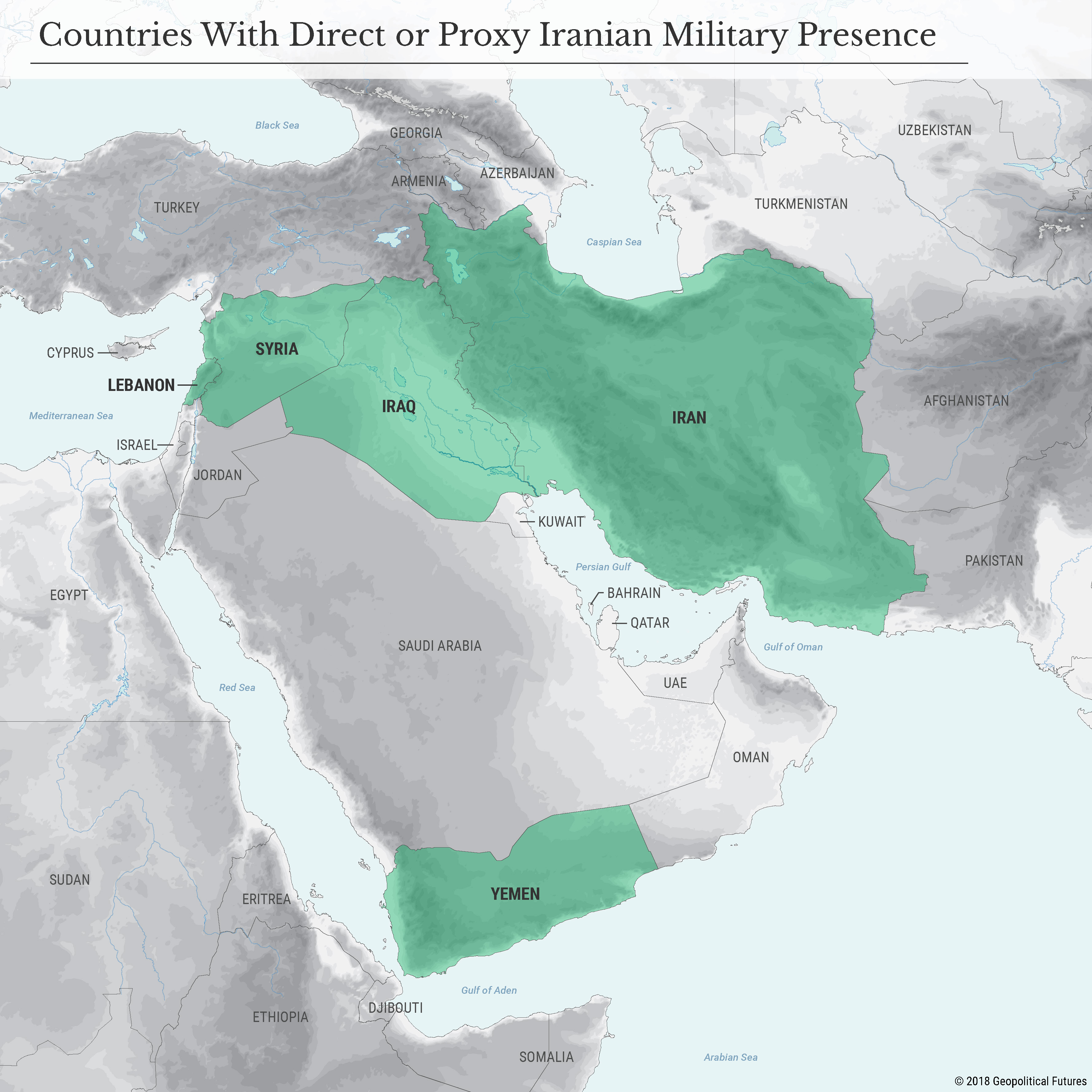

Ground force is a less likely choice for the U.S., even with limited objectives (like eliminating specific military equipment or securing passage through the Strait of Hormuz). But it would be more likely to achieve what the U.S. really wants: for Iran to recall its foreign militias so that they will defend the home front. But when a military force is rapidly removed without a replacement ready to take its place, it creates a power vacuum and, therefore, an opportunity for others to fill the void. In this case – the Islamic State and other jihadist groups. Timing matters too. The pace at which Iran withdraws its militias from Syria and Iraq, states that are already precariously fragile, will create an outsized risk to violently alter the regional balance of power.

If the Islamic State moves back into the space vacated by Iran, it would be the U.S. that would have to again deal with this problem, which would require reoccupying parts of Iraq while fighting Iran. That, in turn, would likely entail support from Syrian and Iraqi Kurdish forces, which would again put pressure on U.S.-Turkey relations. But the Syrian Kurds may not see a long-term alliance with the U.S. as in its best interest after the U.S. threatened to leave them high and dry in December 2018. They could instead seek out a political resolution with Damascus, backed by Russia, that would protect them from Turkey. It’s possible that if the Islamic State re-emerged, Russia could step in to back Kurdish groups such as the Syrian Democratic Forces to fight back. But that would mean the U.S. would be depending on Russian assistance to cover its western flank, and in exchange for such cooperation Russia would likely demand U.S. concessions in places like Ukraine. In short, going all-in with Iran would require either a large-scale U.S. occupation or dependence on Russia in Syria and Iraq to prevent the Islamic State from coming back. Neither of those are appealing options for Washington.

If it’s regime change that the U.S. is after in Iran, the risks are even greater. The fallout would look much like that of the second Iraq war, but on a far greater scale. Installing a pro-American regime isn’t easy, but it can easily fail. The U.S. would have to commit to an indefinite occupation of Iran or again risk the emergence of a power vacuum. And it would still have to deal with the rest of the Middle East. In the best-case scenario, the U.S. would install a new head of government while facing a lengthy insurgency, which would likely include the vestiges of the IRGC and its heavy weaponry. After a long, costly occupation, the U.S. would withdraw, leaving Iran’s leaders to face opposition on their own. The half-life of U.S.-installed leaders in the Middle East is not long – just ask the shah of Iran.

Whether limited airstrikes or a full-scale invasion, a U.S. military confrontation with Iran would create more problems for the U.S. than it solves. As barbs are traded on the international stage, it’s these kinds of strategic considerations that Washington will need to consider before going to war.

No comments:

Post a Comment