Ben Jonsson

Despite a net loss of territory in Iraq and Syria since January 2016, the Islamic State carried out complex attacks in Brussels and the Philippines and inspired other attacks in Turkey and Asia during the same months. The successful attacks suggest that the Islamic State’s ability to threaten U.S. interests will likely outlast its control of significant swaths of territory. Mitigating the long-term threat of the Islamic State will thus require more than its military defeat on the battlefield in Syria and Iraq.

Despite a net loss of territory in Iraq and Syria since January 2016, the Islamic State carried out complex attacks in Brussels and the Philippines and inspired other attacks in Turkey and Asia during the same months. The successful attacks suggest that the Islamic State’s ability to threaten U.S. interests will likely outlast its control of significant swaths of territory. Mitigating the long-term threat of the Islamic State will thus require more than its military defeat on the battlefield in Syria and Iraq.

The United States must challenge the Islamic State’s powerful messages even as its territory recedes. Understanding how the Islamic State portrays its struggle for Syria can offer insights on how to challenge its survival by addressing its core appeal to constituents.

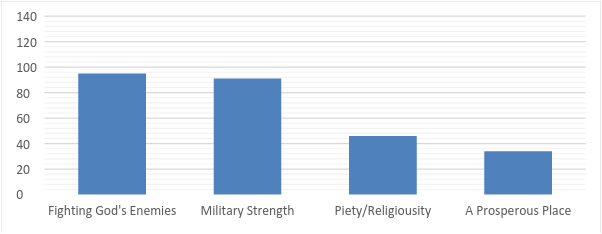

An analysis of 134 Twitter posts from January 1-31, 2016, all allegedly originating from within Syria, revealed four broad themes of the Islamic State’s information campaign.

Strength of its military (victory, targeting, advanced weapons built in the caliphate, spoils gained)

A prosperous place (pictures of nature, orderly streets, filled markets)

Piety in the actions of the people of the caliphate (mercy, justice, prayer, distribution of literature, educating youth, dying for God)

Battle against God’s enemies (Nusayris, a derogatory term for the regime’s Alawite sect; apostate Kurds; Awakening [Sunni] apostates; reports of watchmen on the frontiers of the caliphate—protecting the faith itself)

Occurrence of Each Theme Across 134 Tweet

The first two themes (the second and fourth columns in the chart above) were explored in a previous article on America’s underperformance on the Twitter battlefield, highlighting the importance of counter-messaging efforts in confronting the Islamic State. The Islamic State’s portrayal of its military strength and the prosperity of the caliphate should be directly challenged by creating pictorial and video content with Arabic text and audio that shows the truth—Islamic State battle losses and bad governance in areas such as taxation and conditions of the poor, revealing the totalitarian nature of the Islamic State. Notably, some content of this type has begun to appear. More still needs to be done, particularly better pictorial reports of the Islamic State’s military losses.

The second two themes, the Islamic State’s portrayal of its religiosity and its fight against the enemies of Sunnis, are more difficult to directly undermine on social media. However, the United States must respond to and contest the powerful appeal of these latter themes in order to weaken the threat of the Islamic State. The strategy should include advancing Sunni interests both on the battlefield and in diplomacy, anticipating enduring jihadist threats emanating from Syria, and enhancing cooperation with regional religious authorities.

THE APPEAL OF FIGHTING GOD’S ENEMIES

Many Sunni militants view the fight against a belligerent Iran and its proxies in the region, and by extension the Syrian regime, as an imperative. When it comes to the question of who will guarantee the best future for the Sunni people of Syria, the Islamic State responds with the insistence that it is God’s army fighting God’s enemies. The theme of the Islamic State’s battle against God’s enemies is emphasized in 94 of the sampled 134 Twitter posts, including the extensive use of Koranic verses and the exclusive use of the term Nusayri for regime forces. Nusayri is a reference to Ibn Nusayr, the man believed to have propagated the regime’s Alawite sect in the 9th century, and implies that the sect was founded by man-made ideas and is therefore not Islamic. Similarly, references to clashes with the Kurdish forces are always preceded by terms such as “apostate” or “atheist,” as are depictions of slain Sunni Arabs, killed by the Islamic State. These non-Islamic State, Sunni Arabs were also referred to as “awakening apostates.” The “awakening” term was first used for the Sunni Muslims in Anbar who sided with the United States against Al Qaida in Iraq (which later became the Islamic State) in 2007-2008, ostensibly portraying those Sunnis who fight against the Islamic State as Western agents.

The assertion that the Islamic State is fighting against God’s enemies gives the group a religious appeal and sense of mission with which few governments or rebel factions can compete—especially Arab states viewed as serving their own interests rather than the faith of Islam. The rule of Bashar Al Assad’s Alawite sect through decades of brutal oppression, in the context of a regional struggle for domination between Shia and Sunni power-centers, created a space for religiously-motivated militancy. While the Islamic State dominates this space, there is competition for the opportunity to represent the aspirations of Sunni militancy, as demonstrated by the strength of Jubhat Al Nusra, Jaish Al Islam, Ahrar Al Sham, and other militant Islamist groups.

THE APPEAL OF PIETY

Not only does the Islamic State frame its legitimacy with its theme of fighting God’s enemies, but it also demonstrates the group’s piety in 46 of the 134 tweets sampled. The Islamic State presented the ideas of mercy, justice, religious activity, commitment unto death, and even the training of children in a religious workshop. In a counterintuitive way, the three criminal executions the Islamic State tweeted portrayed swift justice, a notion that may be appealing to people often victims of rampant corruption. While the Western world focuses on the brutality of the Islamic State, this analysis suggests that the Islamic State spent the first month of 2016 strengthening its core narrative of pious religionists. For Western audiences, the irony seems so stark as to not be believable. However, for an organization proclaiming itself a religious caliphate, the strict adherence to Islamic religiosity and jurisprudence is crucial. As other research has suggested, the Islamic State has a narrow and selective interpretation of Islamic jurisprudence, one that is not representative of the developments in Islamic law over past centuries. However, religious appeal should not be overlooked since it is a key feature of the Islamic State’s portrayal of its activities in Syria.

Not only does the Islamic State frame its legitimacy with its theme of fighting God’s enemies, but it also demonstrates the group’s piety in 46 of the 134 tweets sampled. The Islamic State presented the ideas of mercy, justice, religious activity, commitment unto death, and even the training of children in a religious workshop. In a counterintuitive way, the three criminal executions the Islamic State tweeted portrayed swift justice, a notion that may be appealing to people often victims of rampant corruption. While the Western world focuses on the brutality of the Islamic State, this analysis suggests that the Islamic State spent the first month of 2016 strengthening its core narrative of pious religionists. For Western audiences, the irony seems so stark as to not be believable. However, for an organization proclaiming itself a religious caliphate, the strict adherence to Islamic religiosity and jurisprudence is crucial. As other research has suggested, the Islamic State has a narrow and selective interpretation of Islamic jurisprudence, one that is not representative of the developments in Islamic law over past centuries. However, religious appeal should not be overlooked since it is a key feature of the Islamic State’s portrayal of its activities in Syria.

The United States should strengthen alternative forces in Syria that have similar appeal to Sunni populations but are less threatening to U.S. enduring interests. If lessons from Lebanon and Iraq are any indication, creating political terms for multi-sectarian rule is extremely difficult even with a heavy external hand. The United States should assume that the sectarian appeal of the Islamic State will persist, in part because the Islamic State has exploited sectarian tensions through its propaganda efforts to its own benefit. The Islamic State will likely continue to base its legitimacy on appeal to Sunni masses. And while the Russians have sided with Assad in Syria, the United States is better served by recognizing the underlying appeal to Sunnis. U.S. decisions and policies to support Sunnis have been appropriate (like training and equipping Sunni opposition groups), just insufficient or too belated to make a substantial impact. As the Syria peace talks continue in Geneva and Vienna, the United States should advance Sunni interests in order to diminish the chance that only the Islamic State can meet the legitimate demands of the majority of the population.

Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov (left) and Secretary of State John Kerry (second from left) attend the International Syria Support Group meeting in Munich, Germany, on Thursday along with members of the Syrian opposition and other officials, 11 February 2016. (Michael Dalder, AP)

The effort to support Sunni interests should include creating space for Islamic State militants that are willing to leave the organization in exchange for a seat at the negotiation table. Doing so could help splinter tribes, and less ideologically-oriented Sunni groups, away from the Islamic State, thus decreasing the size and strength of the organization. The U.S. should also consider promoting a decentralized power structure for Syria whereby Sunni self-rule would become institutionalized, in essence recognizing political representation in the de facto Sunni regions. This would likely necessitate agreement on a no-fly zone to limit attacks between regime and opposition forces. The no-fly zone plan should be coordinated through the International Syria Support Group (ISSG--the body that includes Russia, Iran, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and the U.S.) and backed by a United Nations resolution. Protecting Sunni interests in Syria would also mean transitioning Assad out of power on a recognized timeline between 6 and 12 months. Deferring on the status of Assad helped bring Russia and the Syrian regime to the negotiations table, but transitioning him out of power remains a critical demand for Sunni opposition groups. Russia can still be accommodated in their quest for continued influence in Syria if the U.S. allows them to help shape who controls Damascus and the western port of Latakia. Finally, advancing Sunni interests also means building relationships with power-brokers in Sunni-dominated regions, and strengthening non-Islamic State groups through targeted assistance in communications, civil society, and community policing.

An important warning is necessary. In strengthening alternative Sunni forces, the United States runs the risk of stoking Sunni militancy by encouraging actors who may scarcely different from the Islamic State. The United States has criticized its allies of doing exactly that, fueling Sunni militancywithout careful evaluation of who received their weapons and funding. Shrewd application of U.S. resources is required to understand the nature of the different groups, their capabilities, and their threat to the United States over the long term. It is a complex task, but it must be done.

As the United States considers options to weaken the Islamic State’s appeal, the deeply religious nature of the organization is instructive. There is no set of policies that will eliminate the threat of radical Islamists wanting to harm the United States and its interests, even if the Islamic State is decisively defeated in Iraq and Syria. Remember that the Islamic State formed out of the ashes of a near-complete defeat of Al Qaida in Iraq by the end of 2010. While core Sunni grievances in Iraq certainly strengthened the position of its remaining leaders, its quick rise back to power demonstrates the strength of its narrative, which is deeply sectarian and religious. At the core of the Islamic State’s ideology is an interpretation of the Koran that is militant and expansionist.

The United States must remain clear-headed and discerning in its approach. A political solution in Syria is a necessary part of minimizing the threat of religious militancy, by depriving the Islamic State of its unique position as an alternative government that provides for the rights and protection of the Sunni population in Syria. However, as various extremist groups have flourished in Syria, the United States should expect a strong jihadi undercurrent to persist. Therefore, it must design policy and security arrangements inside of any negotiated settlement and transitional government that are informed by that threat. For example, a regional coordination center should be established by the International Syria Support Group that builds on previous ceasefire monitoring but expands to report on violent extremism.

The United States should also carefully consider the prominence of religious messages in the Islamic State’s appeal. For example, for all of President Obama’s missteps in Syria, the decision to not commit a large ground force has meant that the Islamic State targeted the Nusayris and the Kurds as its principal enemies. If the U.S. had committed ground forces, it might have played into the religious narrative of the Islamic State that prophetically believes in a final battle against “Rome” or the West. Those who advocate for a large U.S. ground combat role should anticipate how the Islamic State might exploit U.S. intervention in a religious context, validating their call for the final battle for all Muslims at Dabiq.

THE ROLE OF ISLAMIC AUTHORITY

Exterior view of al-Azhar Mosque (Daniel Mayer, Creative Commons)

The United States should more vigorously pursue regional cooperation in a social media strategy that undercuts the Islamic State’s claims they are God’s people fighting God’s enemies. The potency of the Islamic State’s religious appeal has been the focus of previous efforts to counter the messaging of the Islamic State, attempting to win over would-be jihadists with the powerful voice of moderate Islam. Even President Obama weighed in on the messaging effort with his controversial statement that “ISIS is not Islamic.” While his point that the Islamic State does not represent the 1.6 billion Muslims in the world was accurate, it raised the broader question of who in the Muslim world possesses the power and influence to counter the Islamic State’s messaging in the global media? Do such forces even exist, and presuming that they do, have they been utilized to the maximum extent possible? While there is a natural problem with trying to preach a loud message of moderation, there is more that can be done by religious centers such as Al Azhar mosque in Cairo, the Organization of the Islamic Summit, and coordinated efforts by the Grand Muftis from the Islamic world, such as developing strategies for active social media engagement.

The United States should more vigorously pursue regional cooperation in a social media strategy that undercuts the Islamic State’s claims they are God’s people fighting God’s enemies. The potency of the Islamic State’s religious appeal has been the focus of previous efforts to counter the messaging of the Islamic State, attempting to win over would-be jihadists with the powerful voice of moderate Islam. Even President Obama weighed in on the messaging effort with his controversial statement that “ISIS is not Islamic.” While his point that the Islamic State does not represent the 1.6 billion Muslims in the world was accurate, it raised the broader question of who in the Muslim world possesses the power and influence to counter the Islamic State’s messaging in the global media? Do such forces even exist, and presuming that they do, have they been utilized to the maximum extent possible? While there is a natural problem with trying to preach a loud message of moderation, there is more that can be done by religious centers such as Al Azhar mosque in Cairo, the Organization of the Islamic Summit, and coordinated efforts by the Grand Muftis from the Islamic world, such as developing strategies for active social media engagement.

In the context of sectarian violence in Iraq after the U.S. invasion, an effort began in Jordan in 2004 called the Amman Message, which created a definition for who is a Muslim and eliminated illegitimate practices of calling other Muslims apostates (takfir). It was endorsed in July 2006 by over 500 leading Muslim scholars, and it was an important part of dealing with the religious war in Iraq. However, the Amman Message has not had an active role in addressing the resurgence of sectarianism in Iraq or in Syria. The United States could explore a renewal of the Amman Message as a part of its ongoing cooperation with partners in the region. The first step could be encouraging Jordan’s King Abdullah to initiate a summit in commemoration of the 10-year anniversary of the Amman Message, gathering Islamic scholars to reaffirm its importance in view of the rise of the Islamic State. The summit should include an active social media component that expands its impact with lead-up news, event coverage, and follow-on messaging.

CONCLUSION

To be successful in the long term against the threat of the Islamic State, the United States should focus its power on undermining the organization’s core appeal. The United States must recognize the sectarian nature of the Syrian conflict, which enhances the attraction to the Islamic State as the best Sunni Army in Syria. All U.S. policy decisions must be informed by the need to guarantee the rights and future of Syrian Sunnis, while anticipating increased threats from the growth of jihadi organizations within Syria.

Importantly, coordinating with partners in the region to enhance the influence of Sunni religious authorities is a necessary but insufficient answer to the deep, religious claims of the Islamic State and the enduring threat of Islamic terrorism. The religious appeal of the Islamic State, and groups like them, will enable them to persist despite military and economic setbacks. The best strategy is to minimize that threat by strengthening alternative religious voices from within the region.

No comments:

Post a Comment