NOAH BARKIN

On a sunny afternoon in early April, about a dozen diplomats from European and other allied nations gathered with their American counterparts around a conference table at the State Department. In a month’s time, China’s President Xi Jinping would host a summit in Beijing to celebrate his grand infrastructure project, the Belt and Road Initiative. The Americans wanted to send Xi a message.

At the meeting in Washington, D.C., they pressed their allies to sign on to a joint statement condemning the Chinese plan. But it soon became clear that neither the Europeans nor a small group of other countries from Asia and Latin America were ready to fall in line.

“No one was willing to go along with it,” one European diplomat familiar with the details of the meeting, who requested anonymity to discuss sensitive negotiations, told me. “We may agree that China is a strategic threat, but you can’t just put them in a corner.”

For the Europeans, the meeting at the State Department was another sign of what they see as the White House’s misguided zero-sum approach to dealing with China, and its mistaken belief that it can employ an à la carte approach with its partners, denouncing them publicly on some issues while expecting cooperation on others. For the Americans, the talks were the latest sign of Europe’s reluctance to stand up to China. “Europe,” one person close to the Trump administration who declined to be named told me, “is almost on a different planet.”

After two years of escalating tensions between the United States and Europe over issues ranging from trade and Iran to defense spending and Russian gas pipelines, China should be the issue that unites the two sides, or at least eases some of the transatlantic strain.

The European Union—with Germany and France leading the way—has adopted a much tougher stance on China over the past year, introducing new rules allowing for closer scrutiny of Chinese investments in European countries, exploring changes to the EU’s industrial, competition, and procurement policies to ensure Beijing is not unfairly advantaged, and, after years of avoiding clashes with Beijing, declaring China a “strategic rival.” This shift mirrors the harder line adopted by Washington under President Donald Trump, who has dialed up his two-year confrontation with Beijing several notches over the past month by raising tariffs on Chinese goods and putting the Chinese telecommunications group Huawei and scores of its affiliates on an export blacklist that could severely restrict their access to vital U.S. technology.

But conversations I had with dozens of officials on both sides of the Atlantic—many of whom requested anonymity to talk about diplomatic and intelligence issues—suggest that instead of coming together, Europe and the U.S. might be in the early stages of a damaging divergence on the China challenge. Trump’s latest moves, which raise the specter of a prolonged economic Cold War between Washington and Beijing, are likely to deepen the divide, taking the U.S. down a path that is unpalatable for even the hardest of European hard-liners.

“If you listen to the people in the Trump administration, who view China as an existential threat, they are not in a place most Europeans can get to,” says Evan Feigenbaum, who held senior Asia-focused roles in the State Department during George W. Bush’s presidency and is now at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

The dissonance raises the prospect of a Western split on what both sides agree is likely to be the biggest geopolitical challenge of the 21st century—responding to the rise of an authoritarian China.

A series of meetings in recent months, and the disparate ways in which they were interpreted by either side, illustrate the widening chasm. The European diplomat who discussed the April meeting likened Washington’s uncompromising stance on Belt and Road to its position on the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) a few years prior. Back then, the United States, under President Barack Obama, failed to convince allies to join a boycott of the new China-led development bank, leaving the Americans embarrassed and isolated.

U.S. officials, by contrast, point to talks months before the meeting in Foggy Bottom, when Washington was pushing for a joint declaration denouncing human-rights abuses in Xinjiang, the western Chinese region where more than a million members of the Muslim minority have been detained in reeducation camps. That effort was also abandoned after what U.S. officials described as an exasperating back-and-forth with the European Union and individual member states.

Among the American officials I spoke with, there was an air of what felt like panic—over what they saw as the global spread of Chinese influence through Xi’s Belt and Road initiative, the lack of an American alternative to Huawei, and the persistent failure of the World Trade Organization to tackle China’s unfair trade practices.

One senior administration official likened discussions of China policy to the period after the 9/11 attacks. Inevitably, this person said, there will be an “overreaction” from Washington, with “collateral damage” for other countries, before U.S. policy settles down. In Brussels, senior officials are comparing the Trump administration’s China policy to Brexit. Both, they say, are based on the deluded notion that a fading great power can reverse the course of history and return to its glorious past.

The irony is that senior U.S. administration officials acknowledge in private that American success in its competition with China might ultimately hinge on what happens in Europe. Yet many U.S. officials have no patience, at least in the highest ranks of the Trump administration, when it comes to working with European allies. Nor do they have much appreciation for the steps Europe has taken over the past year to push back against China. Several U.S. officials described the EU’s recent measures as baby steps that fall far short of what is needed.

“The Americans are out to beat, contain, confront China,” a senior EU official who asked not to be identified told me. “They have a much more belligerent attitude. We believe they will waste a lot of energy and not be successful.”

This does not mean that transatlantic channels of communication on China have broken down. A group of hawkish pragmatists including Matt Pottinger, who oversees Asia policy at the National Security Council, and Randall Schriver, a senior Pentagon official, have been trying to reach out to Europe for months, U.S. and European officials confirm.

Last year, discussions focused on measures to protect against Chinese acquisitions. More recently, they have shifted to talks on next-generation 5G mobile networks, as well as joint responses to Belt and Road, an issue about which Washington and Brussels agreed last month to hold quarterly coordination meetings, according to EU officials. And last month, an American delegation traveled to Berlin for talks with German officials on China as part of a biannual get-together that began under the Obama administration and has continued, without a hitch, under Trump.

Other changes are under way too: Last year, according to U.S. and European officials, the State Department appointed China point people in many of their European embassies, with officials estimating that roughly 150 U.S. diplomats on both sides of the Atlantic now spend at least part of their time focusing on China in Europe; at a meeting of NATO foreign ministers in Washington in late March, China was on the agenda for the first time; and Belt and Road could be a discussion point when France hosts a G7 summit in Biarritz in August, European officials have suggested.

The outlines of what a transatlantic agenda might look like are not difficult to discern. In responding to Belt and Road, the U.S. and Europe could work together to develop common transparency, environmental, and social standards for infrastructure projects, while pooling their financial resources. At the very top of the priority list would be a set of common rules for data privacy and artificial intelligence, alongside joint efforts to make telecommunications infrastructure and supply chains bulletproof against Chinese espionage and sabotage.

In Washington, some officials I spoke with suggested that a transatlantic consortium—grouping Huawei’s European rivals Nokia and Ericsson with U.S. firms—could be the solution to the 5G conundrum. On trade, the U.S. and Europe could form a powerful coalition with Japan, Canada, Australia, and other like-minded democracies to push back against unfair Chinese practices, perhaps in a comprehensive joint complaint to the World Trade Organization. (The Trump administration’s cooperation with other countries on trade has been limited, though, beginning with the president’s withdrawal of the U.S. from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a trade deal aimed in large part at containing China.)

Some China hawks in Europe are holding out hope that progress on a more comprehensive agenda could come if a Democrat replaces Trump in 2020. While all the leading candidates, including Joe Biden, Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, and Pete Buttigieg, have been critical of China, they have stressed the need to work more closely with allies in pushing back against Beijing.

Still, Europeans should be careful what they wish for. The bullying tone that the Trump administration has frequently employed with Europe on China might disappear if a Democrat enters the White House. But so would one of the Europeans’ main excuses for not compromising with the United States on China and a range of other issues: Trump himself. Europe has profited in the short term from Trump’s confrontation with Beijing, wringing concessionsfrom a Chinese government desperate to prevent a transatlantic front.

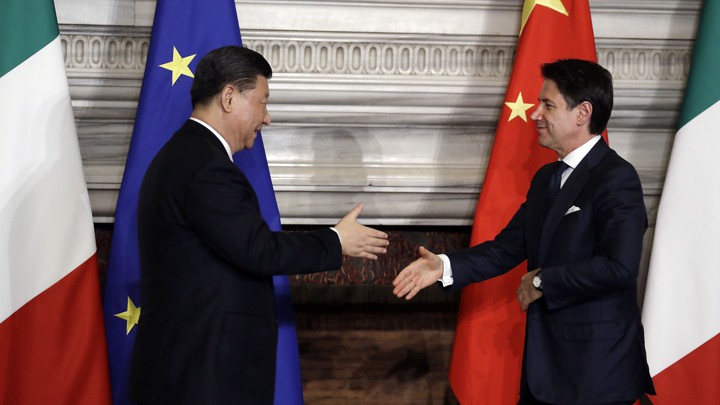

When Xi held his Belt and Road summit in April, half a dozen EU heads of state and government attended, while the Americans stayed home. European companies continue to invest heavily in China, including in sensitive new technologies such as artificial intelligence. When push comes to shove, will the Europeans be ready to give up the advantages they have gleaned from playing the nicer cop? Will they be prepared to put long-standing commercial ties with China at risk? And will they consider assuming more of the military burden in their own backyard as a future U.S. administration pares back its security commitments in Europe to help pay for domestic priorities like health care, education and infrastructure?

“You may have more civility at the top with the Democrats,” says Orville Schell, the director of the Center on U.S.-China Relations at the Asia Society. “But there is no constituency anywhere in American politics right now for cooperation with China.”

Regardless of who is in the White House, European countries must prepare for a world in which they will be viewed by Washington through a China prism—much in the same way that Europe was seen through a Soviet lens during the Cold War.

If no common agenda is possible, the transatlantic relationship might be headed for even more trouble, Trump or no Trump.

No comments:

Post a Comment