Xander Snyder

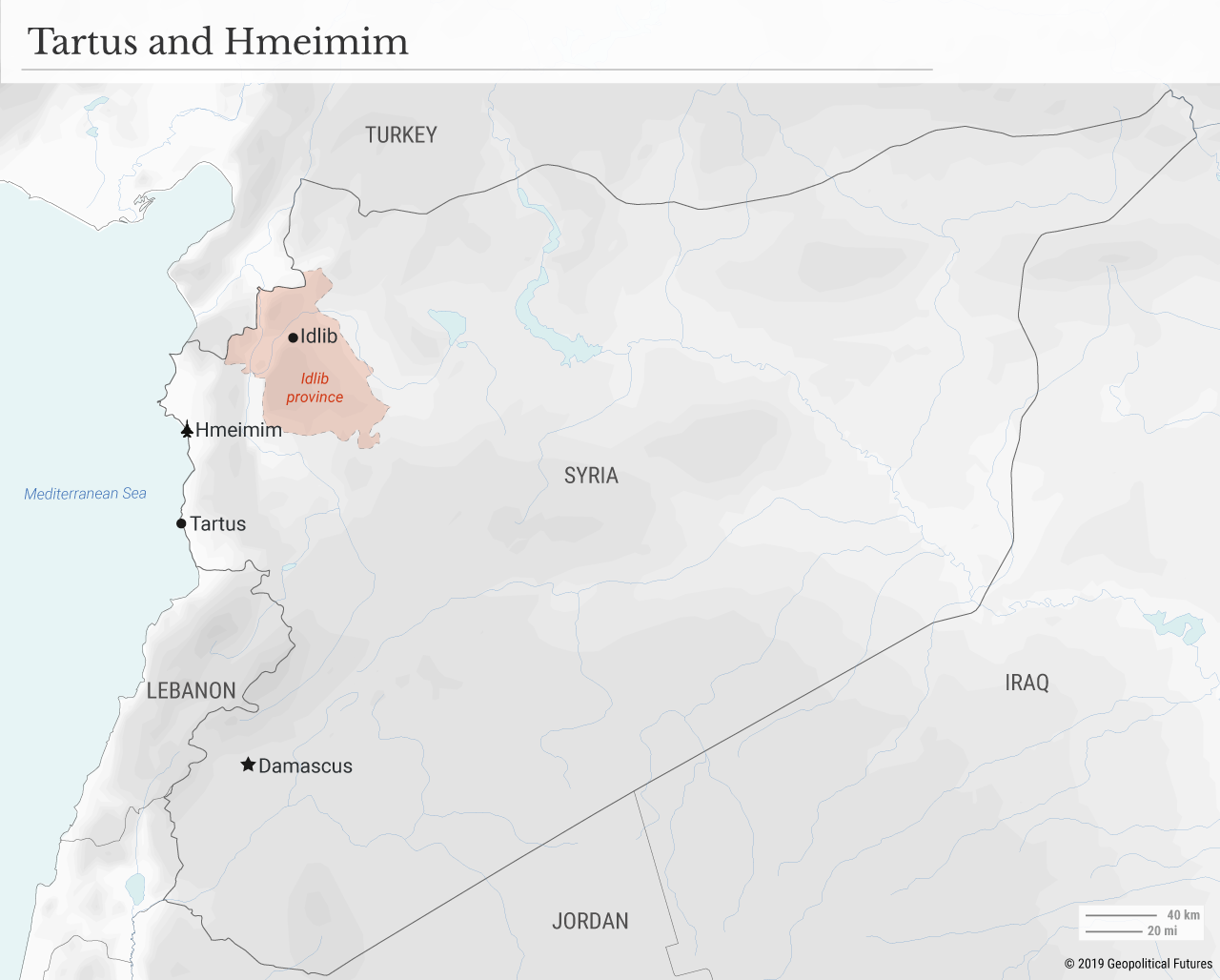

The U.S. and Russia may be at odds from Ukraine to North Korea, but they appear to be much more aligned in Syria, where neither wants to see Iran gain a substantial foothold. As the Syrian civil war winds down, Moscow wants to make sure that it – not Tehran – remains the primary benefactor of President Bashar Assad; that it retains its bases at Tartus and Hmeimim; and that Iran’s presence in the Middle East is curbed. These interests may account for the reports of increasing competition between Russia and Iran in Syria, including skirmishes between groups supported by each.

The U.S., of course, is trying to halt Iran’s advance across the Middle East. It’s unlikely the U.S. can fully displace Iran from Syria, but at minimum it wants to limit the number of Iranian ground forces in Syria to prevent Tehran from having a contiguous overland route to the Mediterranean Sea. And so, as U.S. and Russian interests converge and an opportunity for cooperation arises, Russian, U.S. and Israeli officials will meet next week to discuss what’s next in Syria.

Israel: The Linchpin

Israel’s participation is crucial because Israel has in its estimation the strongest interest of the three to keep Iran out of Syria – protecting its territorial integrity. And while both Russia and the U.S. need to curb Iran’s influence, neither wants to attack Iran directly. Both are happy to let Israel do the heavy lifting, at least in southern Syria, where Israel has its own direct interest in pushing Iran and its proxies in Syria away from its borders. While Russia did provide Syria with S-300 missile defense systems, nominally to protect itself from airstrikes, it’s done little else to halt Israel’s attacks on Iranian positions in Syria. Instead, the two have maintained backchannel communications so that Moscow can be notified when Israel intends to strike. Russia has, moreover, reportedly refused to sell S-400 missile defense systems to Iran. Moscow would be wary of providing Iran with air defense systems that could frustrate Israeli airstrikes targeting Iran in Syria. (Iran denied ever seeking to purchase S-400s.)

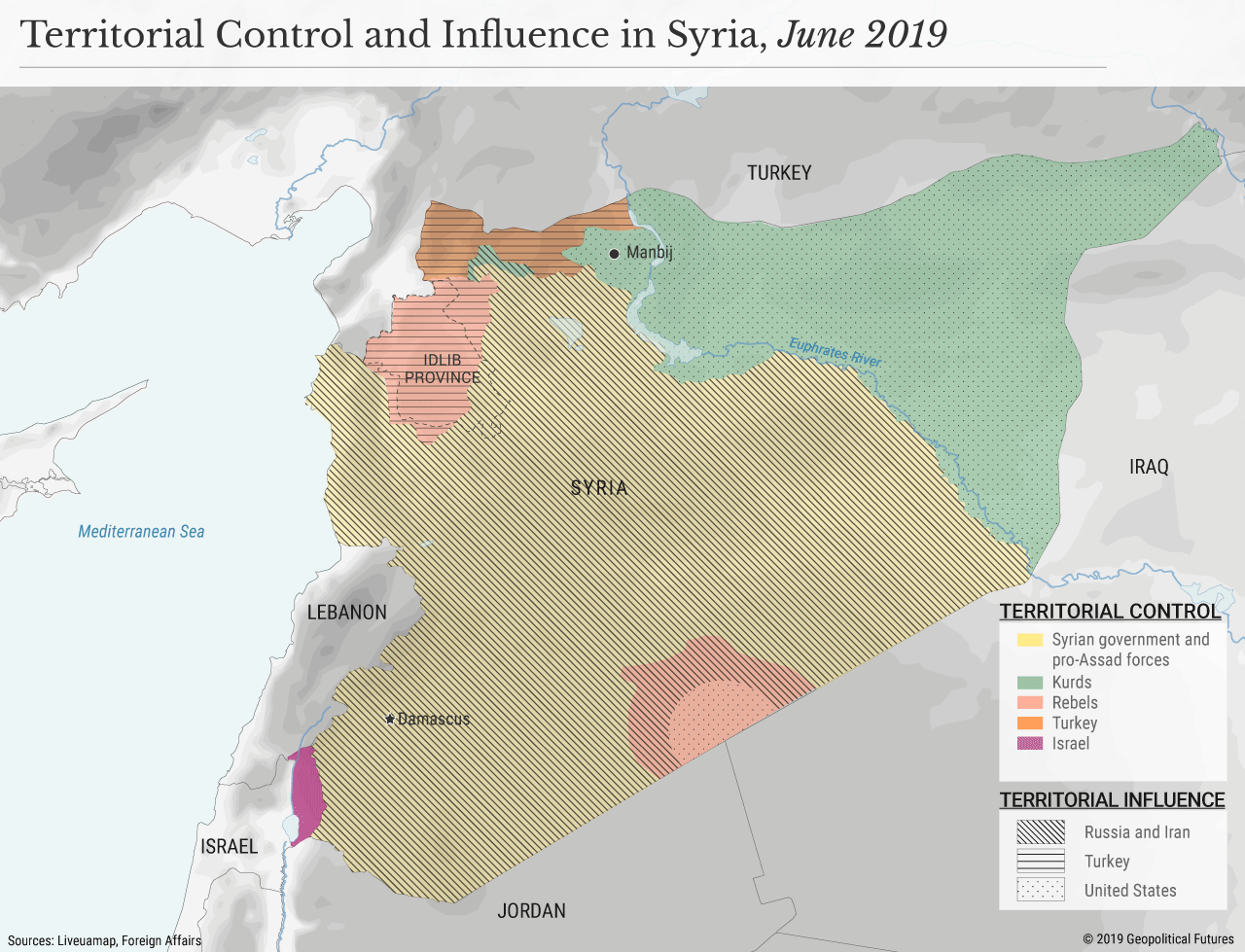

Still, Israel can’t do it alone. While it hammers southern Syria with airstrikes, the U.S. and Russia will have to play their parts in what is, if not an outright alliance, at least a collaborative effort among the three. Russia will continue to support Assad’s ground forces as they reclaim territory and provide ground support through militias like the Tiger Forces, hoping to reduce Assad’s dependence on Iran-backed ground forces. Russia may also play a more political role, trying to lessen Iran’s influence on the Assad regime. In this, it may already be somewhat successful. A recent reshuffle of Syrian security forces weakened the position of Maher Assad, a brother of the president who is believed to be particularly close to Iran. The U.S., meanwhile, will hold onto positions in northeastern Syria, ostensibly in support of its allies like the Syrian Democratic Forces, but also to prevent Iran from seizing the oil fields in that part of the country that could increase Iran’s power in a final political settlement. Iran won’t be willing to directly attack those U.S. forces for fear of retaliation.

And while Russia may complain about the continued U.S. presence in Syria, it at least temporarily serves Russia’s interests by preventing Iran from seizing territory in northern and northeastern Syria and keeping the Islamic State contained to a limited insurgency with no real ability left to threaten the Assad regime. For its part, the U.S. may be willing to exchange cooperation against Iran in Syria for sanctions relief for Russia.

Turkey: The Wild Card

The U.S. presence in northern Syria serves another purpose for Russia: It mitigates the threat of a Turkish invasion from the north. A complete U.S. withdrawal – the kind that U.S. President Donald Trump threatened in December 2018 but subsequently backtracked from – would open the path for Turkey to push further into northern Syria. Russia would rather reach a settlement between Damascus and the SDF than have to account for Turkish demands, which would inevitably be far greater if Turkey held more territory – and therefore greater negotiating power – in northern Syria.

But even in a settlement between the U.S., Russia and Israel, Turkey is the wild card. It’s not that its interests are unclear – it would want to trade its current semi-occupation of Idlib province for greater control over its shared border with northern Syria, where the majority of Syria’s Kurds live. The question is what that control looks like, and how much Assad and Russia would be willing to cede to Turkey in the north in exchange for relinquishing its hold on Idlib to Assad.

Turkey’s issue is that it wants substantially greater control over northern Syria east of the Euphrates River, but on its own timeline. Despite Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s incessant threats to invade northern Syria, he urged temperance when Trump unexpectedly announced a U.S. pullout back in December. Turkey was not ready for the kind of deployment that would be necessary to move into northern Syria on Washington’s timeline and at a scale necessary to hold the territory and eject the Kurdish forces it wanted gone, all the while preventing a recapture of territory by IS. No, Turkey would much prefer to have its cake and eat it too. If the U.S. stays where it is, providing stability in portions of northern Syria, Turkey can selectively and gradually assert control over small pockets of that region.

In a U.S.-Russia-Israel agreement on Iran, Turkey may have to give up Idlib so that Assad can eliminate the rebel presence there without the support of Iranian ground forces. But Turkey would want something in exchange, and it’s possible that Turkey will not be capable of a full-scale invasion of northern Syria before Assad reaches some sort of agreement with the SDF to surrender its autonomy, or before the U.S. decides to withdraw its own forces. Turkey may talk a big game, but having to confront the Syrian government is a different game entirely from attacking ground militias, which is what Turkey has done on its two incursions into Syria so far.

So, what would Turkey get out of such a settlement? Most likely it would take some form of an updated Adana agreement, the 1998 settlement between Turkey and Syria in which Syria agreed not to harbor members of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), and Turkey was allowed limited incursions into Syrian territory (up to 5 kilometers, or 3 miles) to pursue any PKK members that Syria didn’t control. Russia would guarantee the terms of the agreement, Turkey would cede Idlib while retaining some buffer space in northwestern Syria and rights to move into northern and north eastern Syria in order to eliminate specific PKK-related threats when necessary. Turkey may not be thrilled with the result, but it would be enough to meet some of its security needs and wouldn’t necessitate a full-scale occupation of northern Syria, which may be more of a strain on its resources in the long-term than Turkey could handle.

A three-way agreement between Russia, Israel and the U.S. to counter Iran wouldn’t immediately end the Syrian civil war, and neither would it guarantee a complete expulsion of Iran from Syria. But it would be a major step toward establishing shared cause to find meaningful political resolutions to problems that have mired the country in an all-consuming war for nearly a decade.

No comments:

Post a Comment