By Xander Snyder

As if China’s African swine fever outbreak wasn’t enough to worry about, its agricultural sector is now facing down armyworm. The name of this invasive pest is a misnomer: It’s actually a caterpillar, but so named because the swarm progresses methodically plant by plant, destroying large swaths of economically vital crops. Armyworm feeds on 80 different species of plants, including corn. China is the world’s second-largest producer of corn and the plant’s myriad uses – for human consumption, animal feed and other derivative products – means that any impact on the corn supply will affect other related agricultural products in China.

As if China’s African swine fever outbreak wasn’t enough to worry about, its agricultural sector is now facing down armyworm. The name of this invasive pest is a misnomer: It’s actually a caterpillar, but so named because the swarm progresses methodically plant by plant, destroying large swaths of economically vital crops. Armyworm feeds on 80 different species of plants, including corn. China is the world’s second-largest producer of corn and the plant’s myriad uses – for human consumption, animal feed and other derivative products – means that any impact on the corn supply will affect other related agricultural products in China.

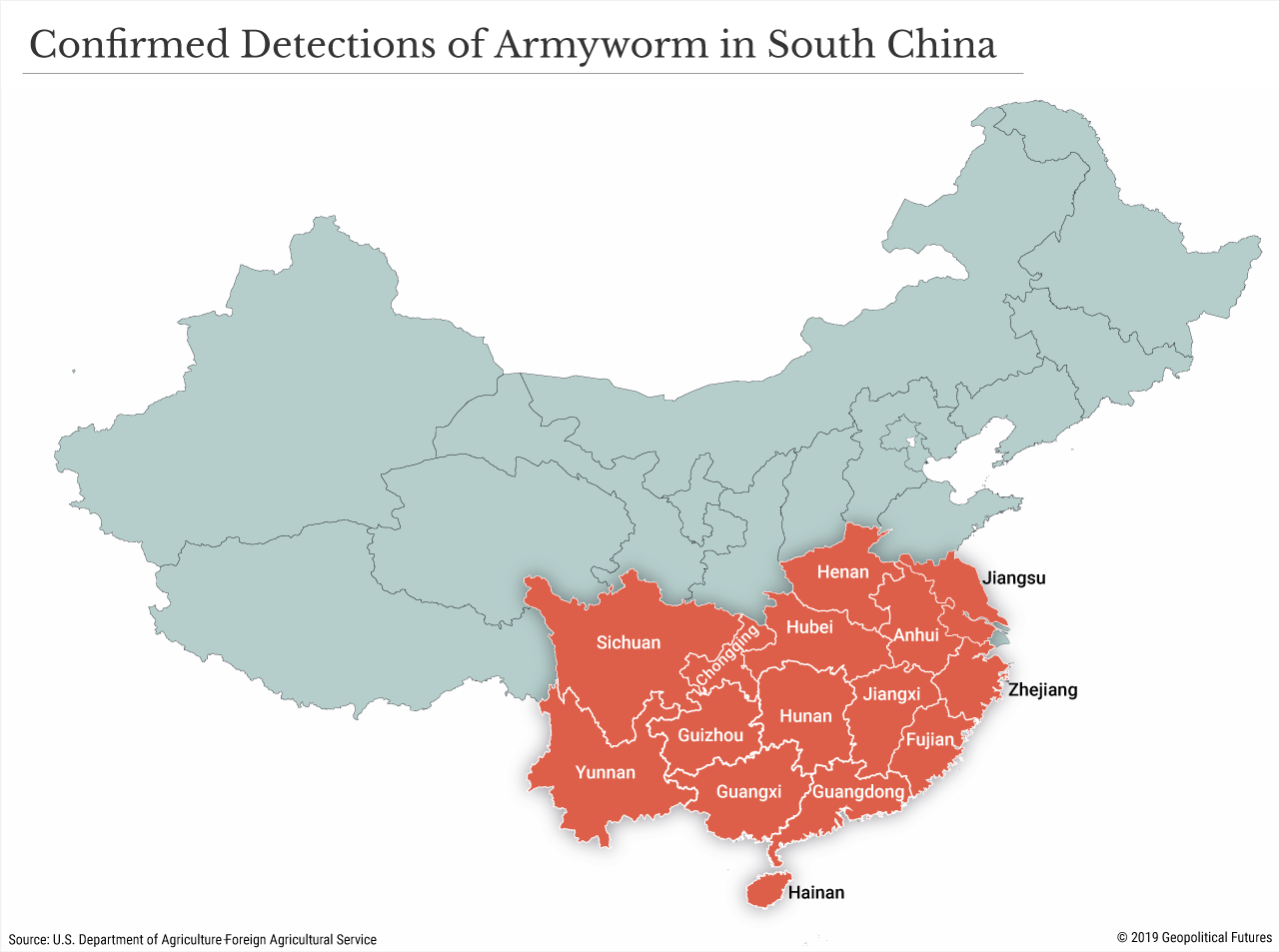

Armyworm is endemic to North and South America. It was first found outside of its native habitats in 2016 in West Africa, after which it quickly spread across the African continent; only 10 African countries have thus far been spared. By 2018, it had made its way to India. The pest was first spotted in China in Yunnan province earlier this year.

It’s hard to find data on how destructive armyworm has been to crops in Africa, in part because much of the on-the-ground data collected has come from one-on-one surveys with farmers, which require them to make a value judgment on how they think the crop would have fared otherwise. Still, estimates of corn crop losses resulting from armyworm’s invasion of the African continent range from 10 percent to 53 percent, a sign that it can cause major damage especially to areas where food scarcity is already a problem.

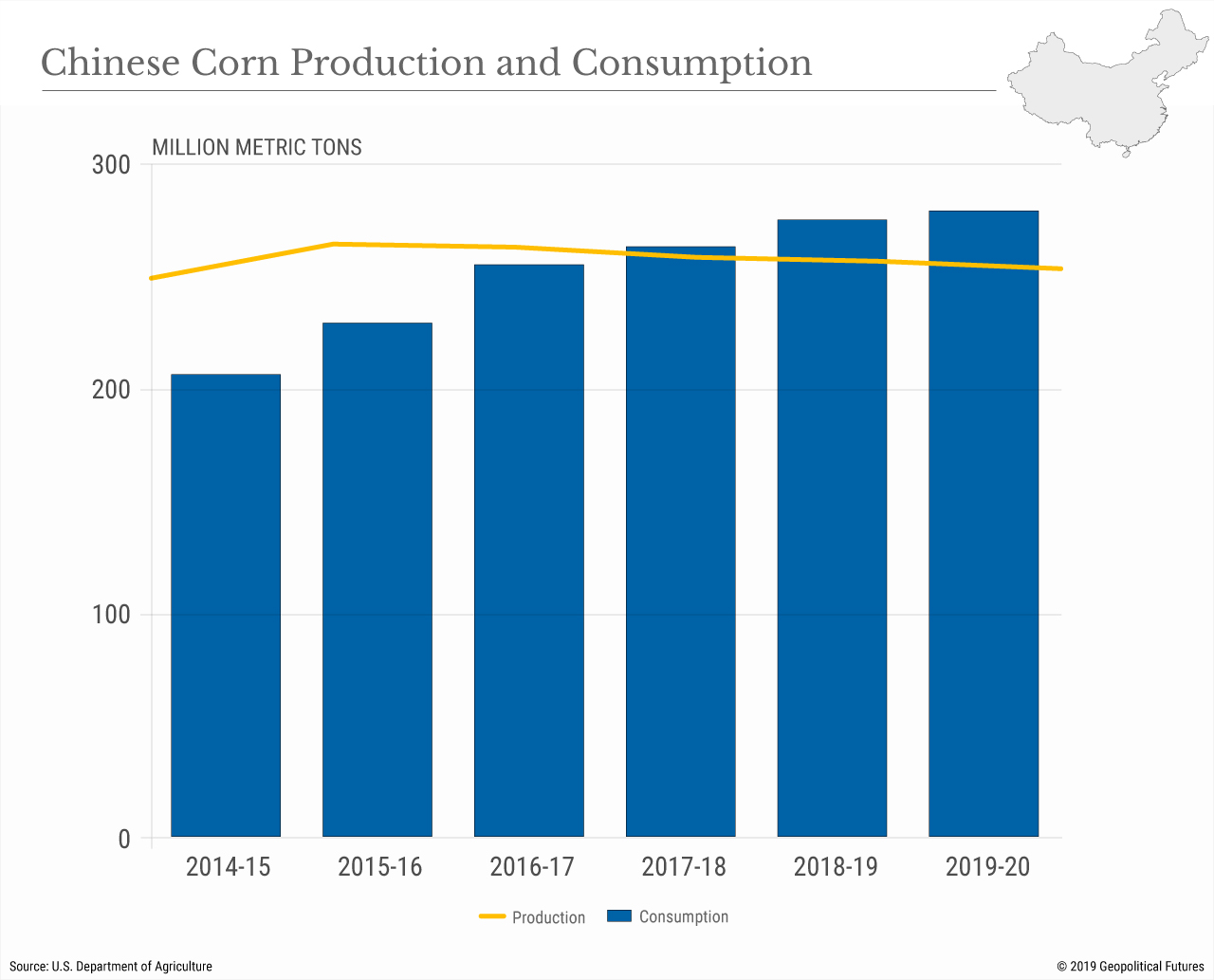

Most of the corn China produces is consumed domestically. In 2018, China produced 257 million tons and consumed 275 million tons – that already puts it at a deficit of about 18 million tons. If the losses sustained by Chinese farmers were comparable to the most conservative estimates for African farmers (10 percent), China would be forced to import more corn or attempt to substitute other crops. But China does not, for now, appear to have a handle on the situation – armyworm has already spread to 18 provinces and is expected to reach the country’s corn belt in the northeast by the end of this month or early next.

If its corn crop is ravaged, where else could China get corn? One obvious option would be the United States, which is the largest corn producer in the world. But, of course, agriculture has been one of the hot-button issues in the U.S.-China trade war. This year, the U.S. passed a $16 billion aid package for farmers to help them deal with losses related to both the trade war and heavy rains experienced in the Midwest (more on this later). Some $14.5 billion will go directly to agricultural producers; the remainder will be used to purchase surplus commodities and distribute them to food banks and schools. This is on top of the $12 billion aid package approved last year to help farmers deal with the damage caused by the trade war. (Unlike last year’s bill, which was paid out based on the number of acres devoted to specific crops, the 2019 bill will pay out lump sums to individual counties.)

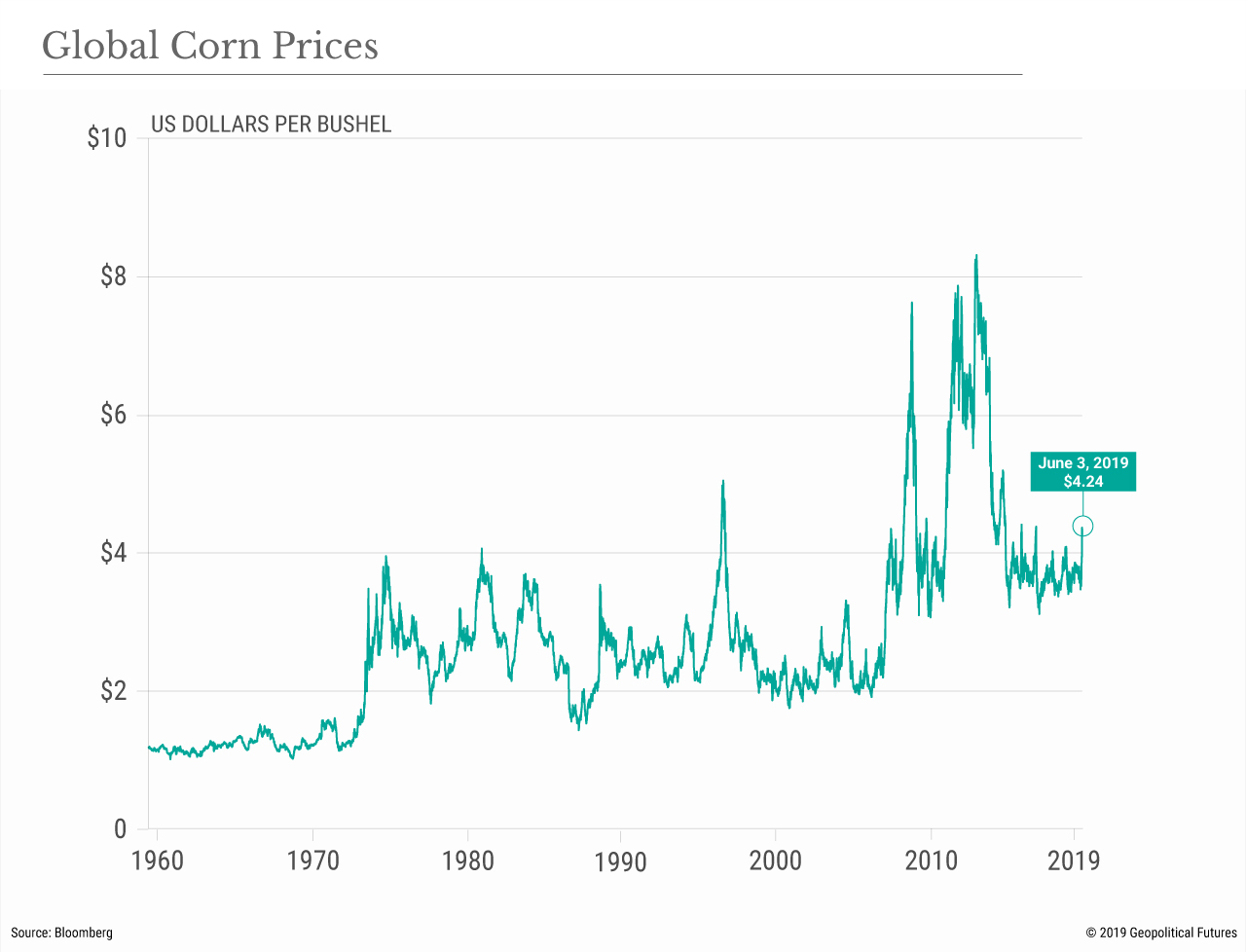

Compounding the losses from the trade war, heavy rains and flooding in the United States’ major agricultural regions have led to significant underplanting; only 58 percent of land was planted this year compared to the 2018 and 5-year average of about 90 percent. Many states are planting even less than the national average; Indiana is at 22 percent, behind its 5-year average of 85 percent, and Illinois at 35 percent, behind its 98 percent 5-year average. Although many farmers carry insurance that covers lower-than-expected crop yield, it requires that farmers actually plant a crop to receive a payout if the business runs a loss. This has left many farmers with a difficult decision: plant the crop despite the poor weather and run the risk of a low yield in hopes of an insurance payout, or don’t plant at all and try to find prevented planting insurance coverage, which pays when farmers are unable to plant crops. All told, the anticipated corn shortage has driven corn prices up to nearly $4.24 per bushel (as of June 3), a nearly two-year high.

So, the U.S. seems like a less-than-ideal source for Chinese corn purchases. China could turn instead to the third-largest producer of corn, Brazil, which, unlike China, produces a surplus and exports a significant amount of corn each year. In 2017-18, Brazil produced a record 82 million tons of corn and consumed only 65 million tons, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. In 2019, corn production in Brazil is expected to increase by 22 percent to 100 million tons, with exports growing 27 percent to 32 million tons. Argentina, too, while a smaller producer of corn at 32 million tons in 2017-18, consumed about 12 million tons and is expected to increase its production and exports this season by 53 percent and 20 percent, respectively. Both countries are expected to produce and export even more for the 2019-20 season (although these growth figures are somewhat lower).

Even if China’s armyworm-related losses are at the low end of estimates – a 10 percent loss of 26 million tons for the 2018-19 season – it would eat up nearly all of either Argentina or Brazil’s surplus. At the high end – closer to 50 percent – neither Argentinian nor Brazilian corn exports could cover China’s shortfall. Only the U.S. could.

China’s armyworm infestation looks like it’s going to make a bad situation worse, putting even greater strain on the country’s food supplies at a time when one of its main suppliers is making it more difficult to buy. Armyworm will likely give the U.S. greater leverage in ongoing trade negotiations with China, but it could also create an area for compromise between the two – more Chinese purchases of American corn.

No comments:

Post a Comment