By Lieutenant Bill Conway

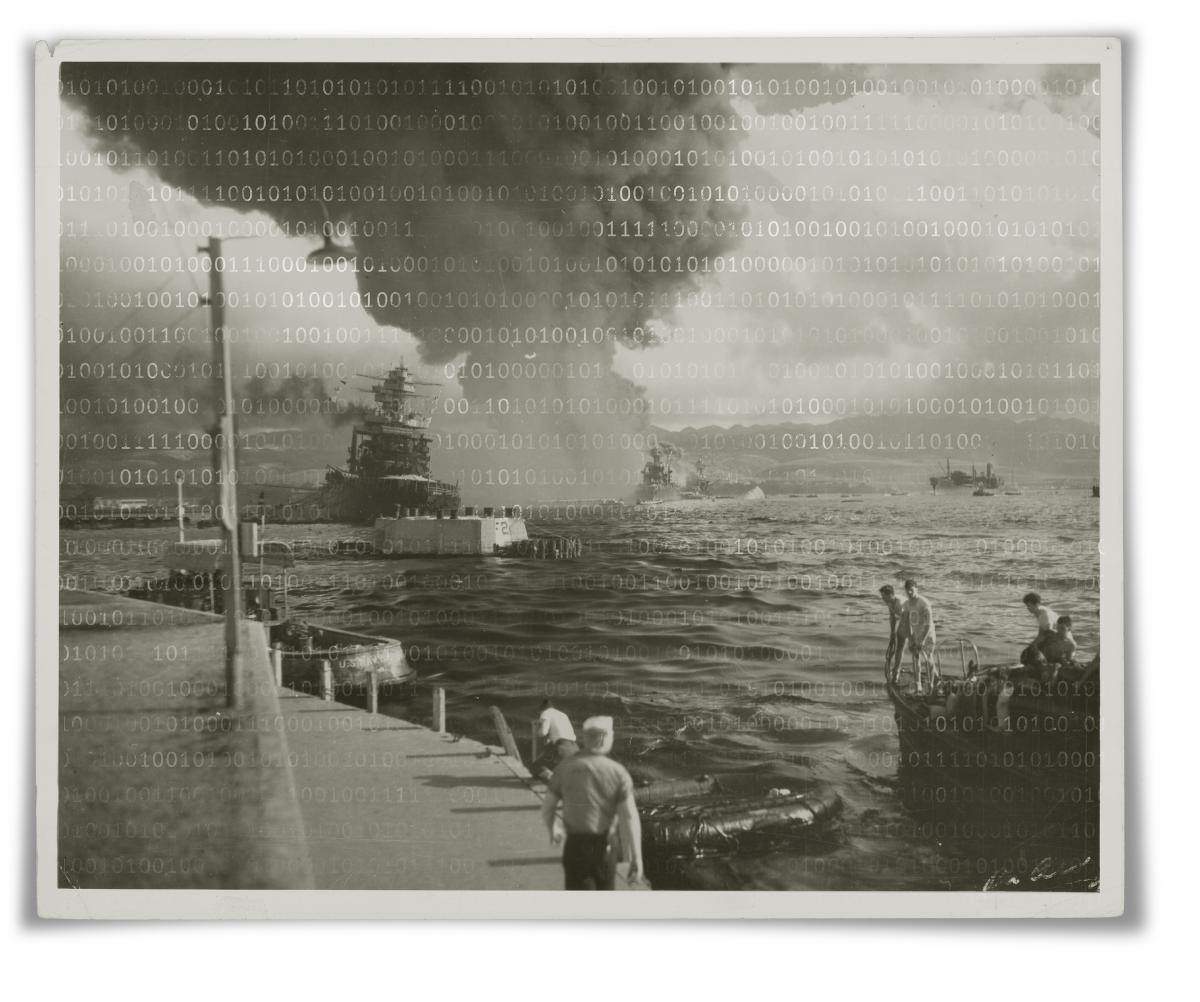

Is it going to take a cyber Pearl Harbor or a cyber 9/11—where the energy grid, water system, banks, and hospitals are attacked simultaneously—for the United States to develop a cohesive strategy to thwart cyberattacks?

Is it going to take a cyber Pearl Harbor or a cyber 9/11—where the energy grid, water system, banks, and hospitals are attacked simultaneously—for the United States to develop a cohesive strategy to thwart cyberattacks?

The Mueller Report detailed how Russian military intelligence, “hacked computers belonging to state boards of elections, secretaries of state, and U.S. companies that supplied software and other technology related to the administration of U.S. elections.”1 Also, the Wall Street Journal reported last month that a U.S. Navy internal report described the Navy and its contractors as “under cyber siege” by global competitors and adversaries. These actors include Chinese government hackers and others who have exploited critical flaws in U.S. cybersecurity.

It’s not just the military and the federal government who are under cyber siege, but all Americans.

In the corporate world, large organizations are under constant cyberattack. In mid-April, the Weather Channel was knocked off the air for more than an hour after a ransomware attack. In February 2018, UnderArmour’s MyFitnessPal app was attacked exposing information of its 150 million users.

Public corporations are required to report cyber intrusions. The Securities and Exchange Commission recently clarified cybersecurity reporting requirements for public companies requiring them to “take all required actions to inform investors about material cybersecurity risks and incidents in a timely fashion.” Nonetheless, cyberattacks against large and small companies are vastly underreported because companies don’t want to indicate to investors and employees that their data is not safe, and they don’t think law enforcement can help.

These types of attacks will continue. As larger enterprises spend the necessary resources to protect their systems, cybercriminals will either become more sophisticated, or move to more vulnerable targets, or both.

In one instance reported earlier this year, a doctor’s office in Michigan was victimized by a ransomware attack in which they refused to pay a $6,500 cyber ransom. Because of their unwillingness to pay, every medical record, appointment, and bill was deleted, including all backups. As a result, the medical practice had to close.

Ordinary civilians are also under cyber siege. Our wearables, in-home virtual assistants, cell phones, smart TVs, and even our doorbells and home appliances are under attack. But, the most common cybercrime against citizens is identity theft, which is often left to local law enforcement to investigate and prosecute. According to Javelin Strategy & Research, an estimated 14.4 million adults experienced identity fraud in 2018, or 5.6 percent of U.S. adults—and this is likely to increase. According to analysis of public data by the think tank Third Way, less than 1 percent of malicious cyber incidents see an enforcement action taken against the attackers. In other words, cybercriminals operate with nearly complete freedom compared to other criminals.

As a result, street gangs have been moving from the drug trade into cybercrime. The Center for Strategic and International Studies, in partnership with McAfee, estimated that the economic impact of cybercrime in 2017 was $600 billion or 0.8 percent of global GDP, just behind narcotics trafficking in terms of illegal market size—and projected to continue to grow. For example, last September, the California Department of Justice arrested 32 suspects linked to two street gangs, the Bully Boys and the CoCo Boys. They were indicted on 240 criminal counts including identity theft, hacking, and computer access and fraud. According to the California DoJ press release, the criminal groups targeted medical and dental businesses in Northern California, gaining access to social security numbers and bank details, and then used stolen credit card terminals.

Last week, Midshipman Anthony Perry compared current day cyberattacks to actions by the Barbary pirates in the early 1800s and called for a cyber response as aggressive as President Thomas Jefferson’s naval response was then. I agree. Cyberattacks will continue to increase based on how easy they are to perpetrate, the continued growth of vulnerable targets, and the difficulty of catching and punishing cyber criminals. So how can we get ahead of increasing cybercrime that victimizes governments, corporations, and individuals alike?

First, the military needs to create a small, elite, dedicated cyber force to defend against the most sophisticated cyberattacks and to counterattack and shut down the perpetrators. In 1961, President Kennedy spoke of the need to modernize the military “for the conduct of non-nuclear war, paramilitary operations and sub-limited or unconventional wars,” which provided formal underpinnings to the Navy SEALs and other special warfare units. The unconventional warfare of today and the future is cyber warfare, and the United States must have an elite force prepared to combat it.

Second, more resources—both technical and human—must be dedicated to combat cybercrime. The FBI recently shifted its core focus from counterterrorism to combating cyber criminals, which is a big step in the right direction. This was necessitated because of the “pervasive and evolving cyber threat,” according to the FBI. But this cannot be done on the cheap. Cybersecurity Ventures predicts that global spending on cybersecurity products and services will exceed $1 trillion over the five-year period from 2017-2021—growing at 12-15 percent per year, which may be a low estimate.

Third, cybersecurity awareness and training must be increased for everyone. At the national level, the military and FBI need to be able to track the newest cyber threats and disseminate that information to other stakeholders. At the state level, law enforcement agencies need ongoing training to keep up with new technologies and with the evolving schemes of cyber criminals. At the corporate level, companies must increase cyber training, so employees do not open phishing emails and do report system vulnerabilities to their chief technology officer or appropriate managers. At the individual level, each person needs to take responsibility for their own cyber security and be vigilant about not sharing passwords and personal identification information with unknown websites.

Fourth, cyber threats must be given the same level of attention that conventional threats receive. The President is briefed by the Director of National Intelligence (DNI) daily on foreign threats. The DNI should also report and track cyber threats and attacks. To effect this, the DNI should be relabeled the Director of National Intelligence and Cybersecurity (or DNIC) and given this additional responsibility.

Fifth, fighting cybercrime will require a cohesive approach using the integrated skills and resources of multiple stakeholders—including federal, state, and local government, military, private companies, lawmakers, and law enforcement. The National Cyber-Forensics and Training Alliance (NCFTA) has started down this path. Started in 2002 to bring together stakeholders in private industry, government, and academia to share information and provide training, NCTFA needs to be expanded and additional stakeholders added. The military will have an important role in assisting when a foreign government attacks a public or private entity. Private corporations need to be less hesitant about reporting intrusions. Attacks can only be studied by law enforcement when they know about them. “Vaccinating” other agencies’, companies’, and individuals’ networks and devices against bad actors can only happen when threat tactics, techniques, and procedures are studied in depth. Companies should create opportunities, and perhaps even incentives, for employees to report system vulnerabilities before they become subject to attack.

Finally, each state must comprehensively review and update its laws to deal with today’s cyber insecurity. For example, in Illinois, the main law applicable to these types of offenses is a group of statutes together called the Illinois Computer Crime Prevention Law, which covers computer tampering and computer fraud. These became law in 1996 and have been updated minimally since. In 1996, Amazon was two years old, and Google, Facebook, and Instagram had not yet been founded. Cybercrime and cyber security laws need to be updated and tied to resources, training, and a cohesive approach to ensure they can be investigated effectively and prosecuted at the local level. FBI cyber investigators hate to admit they’re brutally overworked and can only investigate the most serious crimes—those resulting in approximately $1 million or more in losses. Therefore, local laws and law enforcement must be capable of dealing with cybercrime that inflicts smaller losses—but even a $10,000 or $100,000 loss would cripple most individuals and even some companies.

To avoid a disastrous outcome, the United States needs a cohesive strategy to counter cybercriminals and terrorists from nation-states to street gangs. Only in this way can the nation stay ahead of the future threats. In the meantime, when you get an email that says you’ve won a million dollars, don’t click on that link!

No comments:

Post a Comment