By Peter Gill

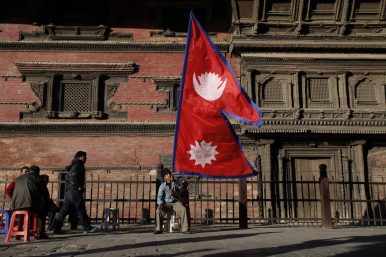

Pessimism about Nepal’s politics is common, despite significant changes since the declaration of the republic in 2008.

Pessimism about Nepal’s politics is common, despite significant changes since the declaration of the republic in 2008.

In Nepal, May 28 marks Republic Day, commemorating the date in 2008 when an elected Constituent Assembly brought an end to the country’s centuries-old monarchy and declared it a federal, democratic republic. This year, the president and a minister marked the holiday by inaugurating a new Republic Memorial at a park that was symbolically carved out of the old royal palace grounds, known as Narayanhiti, in central Kathmandu. But after the VIPs left, the monument did not open to the public as planned. Like many state construction projects, it has faced repeated delays since it began in 2012, and workers are now completing finishing touches and removing scaffolding.

Across the street from the Memorial’s closed gate is a small teashop where office workers and local youth gather in the mornings. Hari Ballav Pant, the shop’s gregarious, grey-mustachioed owner, grew up in the neighborhood and has seen it change dramatically over the years. During the monarchy, he ran a business shampooing carpets inside Narayanhiti Palace. When asked what the new Republic Memorial means to him, Pant replies tersely.

“Look here, at first it was the Ranas who lived off the people, then it was the monarchy; later it was Congress, then the Communists,” he says, referring to Nepal’s various pre-democratic and democratic regimes. “Political change may mean something to the leaders, but it hasn’t made a difference for us common people.”

Pessimism about the state of Nepal’s politics is common these days, despite the fact that the country has experienced significant changes since the declaration of the republic in 2008. At that time, an alliance of civil society leaders, democratic political parties, and ex-rebel Maoists had just finished leading a popular protest movement that overthrew Nepal’s King, Gyanendra Bir Bikram Shah Dev. The alliance was a somewhat uneasy one because its members envisioned different goals. The major political parties called for a return to democracy and civil liberties that had been suspended by the King in 2005. The Maoists, who were coming out of a decade-long rural insurgency, called for a federal state structure, radical transformation of Nepal’s caste-based society, and secularism. All parties agreed on the need to end the economic stagnation gripping the country since the civil war began in 1996, but they disagreed – in theory, at least – about the route to growth and the need for redistributive policies. Today, 11 years on, certain promises of the new republic have been fulfilled. But others, like the construction of the Republic Memorial itself, remain incomplete.

Elections and Inclusive Representation

In a basic sense, the new republic has been successful: elections have been mostly free and fair, with high voter turnout. The Constituent Assembly was formed to write a new constitution in 2008 after an election in which 60 percent of eligible adults participated. Because it failed to draft a new constitution in the allotted timeframe, a second Constituent Assembly was elected in 2013, this time with a record-breaking 78 percent turnout. After this Constituent Assembly promulgated a new constitution in 2015 that reaffirmed secularism and federalism, elections were held in 2017 for central, provincial, and local offices under the new federal structure. Again, turnout was high: roughly three-quarters of those eligible voted in local polls.

Because politics and the bureaucracy had historically been dominated by high-caste men, the Maoists and activists from marginalized castes and ethnic groups pushed for the creation of new, inclusive policies. Today, reserved seats for women, Dalits (so-called untouchables), and various ethnic groups exist in all three levels of government. However, most of these seats fall under the proportional representation category, whereby party leaders choose representatives after the election is over. This system has been criticized for tokenism because it allows the party leaders to overrule seat holders’ dissenting opinions. An affirmative-action system was created for the civil service, but the government has recently sought to roll it back.

Federalism and Secularism

During their insurgency, the Maoists pushed for the creation of a federal state structure to decentralize power from Kathmandu. Later, in 2007-08, Madhesis – a historically marginalized group from the southern Terai region – also led protests in favor of federalism. Federal governance was seen not only as a way to ensure greater local accountability for office holders, but also as way to give ethnic minorities control over government in local constituencies where they formed a majority of the population.

The Constitution of 2015 met some, but not all, of these demands. It created seven new provinces and several hundred local government constituencies. However, most of the provinces were delineated based on geographical rather than ethnic boundaries. Since they were formed in 2017, local and provincial governments have been stymied by disputes with the federal government over concurrent powers, such as those related to taxation and natural resources. The central government, which has the most revenue, has been reluctant to fund provincial governments, and it has delayed reassigning bureaucratic staff to the local and provincial levels. Many question whether central-level officials are genuinely committed to federalism.

Secularism, another hallmark of the new republic, has also had mixed results. During the constitution-drafting process, the Maoists and religious-minority activists pushed for ending Hinduism as the state religion. The Constitution of 2015 declared Nepal secular, but it defined this as “religious and cultural freedom, along with the protections of religion and custom practiced from ancient times,” implying special protections for Hinduism and Buddhism but not newer religions like Christianity. A ban on cow slaughter remains in place, which the Supreme Court has accepted on secular grounds, and opinion polls show that the Hindu majority is unsupportive of secularism. Some mainstream political leaders have even called for a referendum on the subject.

Crackdowns on Civil Liberties

Previous eras of Nepali history have been marked by bans on protests and censorship of the press. Perhaps one of the most important promises of the new republic was the possibility of a more free, open society. However, the government has had a mixed track record regarding civil liberties since the declaration of the republic in 2008.

The constitution-drafting process saw several instances of suppression of speech. When Madhesis erupted in protest against certain aspects of the 2015 Constitution, the police cracked down with excessive force, killing several dozen people. From 2013 to 2016, the government’s powerful corruption watchdog organization was led by a corrupt official who sought to silence media criticism of him.

In the first elections after the promulgation of the new constitution, held in 2017, the Maoists formed an alliance with another party that had hitherto been its rival, the Communist Party of Nepal-United Marxist-Leninist (UML). The Left Alliance won in a landslide, gaining nearly two-thirds of parliamentary seats. The parties merged in 2018, forming the Nepal Communist Party (NCP).

Since coming to power, the NCP government has had rights groups worried. It has used a decades-old law designed to regulate electronic transactions to crack down on online news and social media, arresting six journalists in 2018. In the last few days, Nepali Twitter has been abuzz with calls to release a comedian arrested on charges of defamation for posting a negative film review. More worryingly, a proposed bill could reduce the autonomy of the National Human Rights Commission, an independent government body that plays an important role in monitoring and calling out abuses. In the future, press freedom could be further curtailed by a proposed law that would give government officials the authority to jail or levy hefty fines on journalists they deem to breach a code of ethics.

The NCP government has defended its speech restrictions as necessary to control online abuse, pointing to instances of “fake news.” Following an incident last week when police used water cannons against people protesting an unrelated bill, Home Minister Ram Bahadur Thapa told parliament, “It is the people’s right to peacefully oppose or to support the government, and the government is committed to supporting that right.” However, many people believe the NCP is seeking to control freedom of expression.

Aditya Adhikari, the author of a history of the Maoists, thinks that the current government’s authoritarian tendencies are not unique to the NCP, as some anti-communist critics claim. Instead, he says, a lack of democratic culture among Nepal’s political class was exposed after the NCP gained an unprecedented super-majority.

“Before, no one party had the ability to establish itself as the most powerful – there were always competing coalitions,” he says. “But as soon as one entity comes in and has massive power, then of course they are going to start imposing restrictions, because liberal norms have not been institutionalized in Nepal, ever.”

Biswas Baral, the editor of the Annapura Express weekly newspaper, says that NCP leaders may look to Nepal’s neighbors for inspiration. “In [Chinese] President Xi, [Nepal’s Prime Minister Khadga Prasad] Oli sees a Communist leader who has centralized all powers, and that might inspire him,” says Baral. Likewise, Oli might look to Narendra Modi as a model: the recently re-elected Indian prime minister has also consolidated power and gets generally positive coverage from corporate-controlled media. “I think that must also make Oli think: this is the way you win elections, this is the way you cement power,” says Baral.

Meanwhile, criticisms of the NCP from the United States and Europe begin to sound hollow amid the Trump administration’s anti-media rhetoric and the rise of the far right in parts of the EU.

Growth and Its Discontents

Standing outside the Republic Memorial, a view of Kathmandu’s skyline features several new luxury hotels, high-rise malls, and condominium buildings with apartments retailing at over 10 million rupees (roughly $100,000). Hari Ballav Pant, the teashop owner, looks at them and scoffs. “All the small homes have been demolished to make big buildings. The rich get richer, and the poor get poorer,” he says.

Following the declaration of the republic, Nepal’s GDP grew slowly but steadily until 2014. There was an economic slowdown in 2015-16 due to an earthquake that devastated rural areas, but growth has since rebounded with increased aid and other spending for reconstruction.

However, domestic job opportunities are lacking, and the economy has become one of the most remittance-dependent in the world. The Department of Labor has issued over 3.5 million travel permits since 2008 – mostly for Nepalis bound for the Middle East and Malaysia – while an unknown number of workers travel through informal channels.

Though the Maoists advocated radical economic change as rebels, virtually none of their promises, like land reform, have been carried out since they joined mainstream politics. The current NCP government speaks of passing “progressive budgets” and recently increased the state’s old-age pension, but the social safety net remains extremely weak.

Perhaps more importantly, inequality is perceived as increasing. A recent report by a national think tank argues that a kleptocratic network has taken hold of political parties, public institutions, and the private sector over the past decade, primarily enriching the well-connected elite. Kick-backs are common in infrastructure projects and in procurements, like the recent purchase of an Airbus jet for the national airline. While corruption is a problem across party lines, the current NCP has often sided with big business and cartels, such as when it defied popular protests in January to pass a law benefiting private medical education businesses, seen as a particularly corrupt group.

Growing inequality and corruption has led to popular disaffection. Recently, a rogue group of former Maoists, headed by the dogmatic communist Netra Bikram Chand a.k.a. “Biplav,” took up arms against the government. In February, the group planted a bomb next to an office for Ncell – a major telecommunications company accused of evading taxes – that killed an innocent bystander. In response, the government arrested hundreds of suspected cadres, although many were later released. In one case, the police were accused of summarily executing a suspected Biplav supporter. Home Minister Thapa – a former comrade-in-arms of Biplav – has used harsh rhetoric against the rebels, claiming they are “not citizens.”

It remains to be seen whether Biplav’s group can capitalize on popular frustration with corruption and wealth inequality to grow their movement. Currently, they can claim few supporters and are believed to have only four companies, totaling several hundred armed fighters. But Kunda Dixit, the editor of the Nepali Times weekly newspaper, worries that Biplav could draw more support if the government lashes out wantonly, just as the original Maoist rebels drew support when state security forces committed human rights abuses during the civil war from 1996-2006.

“Thirteen years later, a lot of the former [Maoist] cadres are realizing that nothing really has changed, and things are as bad as the mid-1990s, despite a new constitution, in terms of discrimination, inequality, and exclusion,” says Dixit. “Biplav’s group would not have been able to exist if there wasn’t that disillusionment.”

Remembering to Forget

At the center of the still-closed Republic Memorial is a bus-sized topographical map of Nepal and a concrete sculpture of the country’s new constitution. Above these objects hovers a large, halo-like brass structure that sits on four pillars, each with a dedication: “The ones who were lost;” “The ones who lost their lives;” “The ones who were abducted;” “The ones who were handicapped.”

The Nepali press has criticized the monument for its ambiguity. In a forthcoming paper for the journal Studies in Nepali History and Society, Dr. Bryony Whitmarsh, a U.K.-based professor, posits that visitors will be left wondering to whom, exactly, the memorial is dedicated. Over 16,000 people died and thousands more disappeared in the 10-year civil war. The war led to the party-backed street protests, in which dozens more died, which led to the creation of the republic. Is the memorial for the Maoist fighters? Or for members of other political parties? Or for the police and army? Or perhaps for the innocent victims caught in the crossfire?

Part of the reason the monument contains no list of war dead or disappeared is that no definitive list exists. More than a decade after hostilities between the Maoists and state forces ceased, the country’s transitional justice mechanisms have not yet completed a single investigation into war-time abuses. Attempts to take forward the truth and justice processes have been stymied by the former Maoists, the army, and the opposition Nepali Congress Party, because all of these groups fear that their leaders could be implicated. With thousands of families still waiting to find out what happened to their loved ones during the war, many visitors to the Republic Memorial may wonder: how can Nepal ever face its future, without dealing with its past?

No comments:

Post a Comment