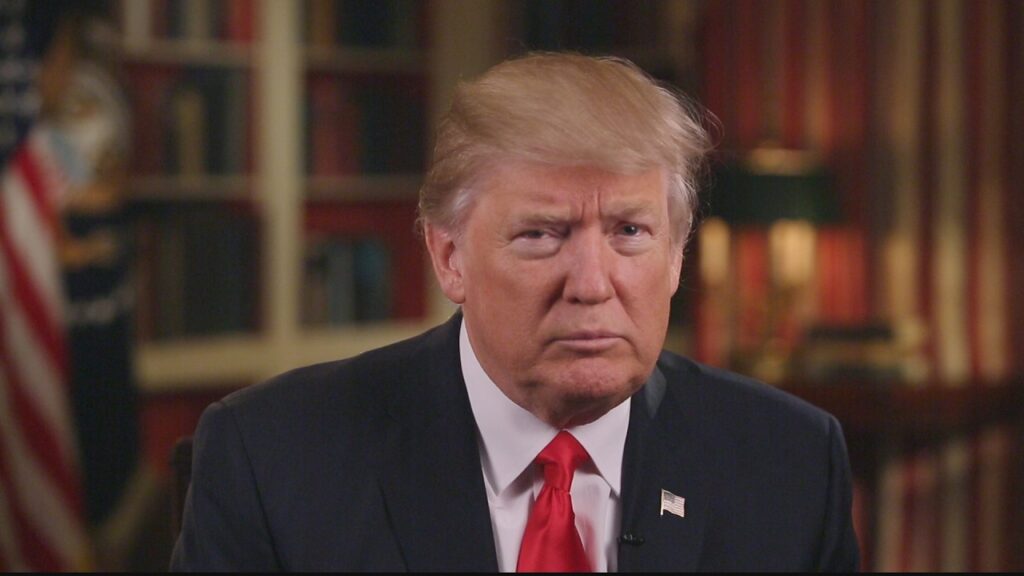

By SYDNEY J. FREEDBERG JR.

WASHINGTON: President Trump’s new Executive Order on imported technology bares sharp teeth at Huawei and other Chinese companies, but it doesn’t have any teeth yet. The actual impact will depend on how the order is implemented over the next 150 days, giving the administration plenty of leverage. That timeline, combined with the wide discretion the order allows — it doesn’t actually mention Huawei or any company by name — gives Trump plenty of leeway. He can use the order as a launchpad for a strict crackdown on suspect tech, or he can use it as a bargaining chip in his larger trade war with China.

WASHINGTON: President Trump’s new Executive Order on imported technology bares sharp teeth at Huawei and other Chinese companies, but it doesn’t have any teeth yet. The actual impact will depend on how the order is implemented over the next 150 days, giving the administration plenty of leverage. That timeline, combined with the wide discretion the order allows — it doesn’t actually mention Huawei or any company by name — gives Trump plenty of leeway. He can use the order as a launchpad for a strict crackdown on suspect tech, or he can use it as a bargaining chip in his larger trade war with China.

But the more cybersecurity gets entangled with protectionism, some experts warned, the less seriously US allies will take American exhortations to keep Chinese tech out of their networks. And what really matters is not how the order impacts the US market — where Huawei is already weak — but the signal it sends to the rest of the world — where the Chinese company has a shot at 5G dominance. This White House’s tendency to sudden reversals that catch its own senior officials by surprise (on nuclear weapons, aircraft carriers, defense spending, Syrian withdrawal, and so on) doesn’t exactly instill confidence abroad.

Timing and context matter, said Elsa Kania, a cyber and AI expert with Center for a New American Security. “I have mixed feelings about the executive order,” she told me. “We needed an E.O. to have the right authorities to exclude high-risk vendors from US networks, [but] it’s been a long time in coming… It was nearly a year ago it first started being discussed.

“I think the delay was problematic, [because] it made it appear that the issuance of it was held hostage to the trade talks,” she continued. “If we are branding this as first and foremost national security, ideally the two issues would be less entangled.”

“In some respects, the way the executive order was framed was a missed opportunity to make a stronger argument, one that US allies and partners could have found more tenable or more appealing,” Kania lamented. The US and its allies had been moving towards an agreed-upon and relatively objective set of criteria to judge tech companies as high-risk, independent of their national origin, she said. The order, by contrast, gives the administration wide discretion to ban companies as it sees fit, based on their connection to hostile nations.

That’s not a good way for the US to convince other countries that Chinese tech is a threat to them, Kania said: “Framing the executive order in terms of ‘foreign adversaries’ is less of a strong argument, [because] not all of our allies and partners do see China as an adversary.”

One example of how an us-and-them approach can backfire is how the Republicans imposed restrictions on US exports of satellite and space launch technology in the 1990s: A joint study by the Commerce Department and the Air Force found it cost the US industry an average of $588 million a year and cut the US share of the global satellite market by more a third. If the US can’t bring its foreign friends and allies along in rejecting Huawei, the 5G market may go much the same way.

Huawei HQ in Shenzhen, China

“Extraordinarily Broad”

Even strong supporters of the order caution that a lot depends on how the administration chooses to implement it. “The E.O. is extraordinarily broad,” said George Mason University intelligence expert Bryan Smith, and that’s a double-edged sword.

Smith has advocated invoking what’s called a Section 232 ban on importing Huawei products. But, he told me, the Executive Order — especially since the administration simultaneously added Huawei on the interagency “Entity List” of bad actors — actually allows a more forceful approach, one that blocks off much-needed exports to Huawei as well.

Bryan Smith

“Subject to subsequent regulatory guidance, the E.O. gives the Secretary of Commerce broad discretion to block any telecommunications transaction with a foreign company that could negatively affect national security,” Smith told me. That would ban not only US imports of Huawei products — which are basically a blip for the Shenzhen-based global giant — but also US exports to Huawei, including key components from suppliers like Qualcomm that the Chinese firm would be hard-pressed to replace.

“Subject to subsequent regulatory guidance, the E.O. gives the Secretary of Commerce broad discretion to block any telecommunications transaction with a foreign company that could negatively affect national security,” Smith told me. That would ban not only US imports of Huawei products — which are basically a blip for the Shenzhen-based global giant — but also US exports to Huawei, including key components from suppliers like Qualcomm that the Chinese firm would be hard-pressed to replace.

Of course, US firms that buy from or sell to the Chinese tech industry would like the administration to clarify its position ASAP. “The aerospace and defense industry is deeply concerned about supply chain security and the protection of sensitive information and our intellectual property. We welcome the high level of attention from the Administration on these issues,” said the Aerospace Industries’ AssociationVP for national security, John Luddy. “We look to the US government for guidance on identifying which goods are essentially commercial in nature and can be traded with the Chinese versus those with military applications that should not.”

That’s the kind of question the 150 days of rule-making need to answer. But the biggest question is not procedural but political, because you can’t consider Huawei in isolation from the wider trade war with China.

“A key issue in the ultimate disposition of this issue is whether the president chooses to use Huawei as a pawn in his broader Chinese trade deal or whether he is truly committed to walling off Huawei from the US (and allied) infrastructure,” Smith said. Given the politics, he continued, “this action will make clear to our allies just how serious the U.S. is about the potential Huawei threat, but most will no doubt view the President’s action as over-reach, with some potentially negative unintended outcomes.”

Chinese President Xi Jinping inspects PLA troops

Almost Perfect?

Nick Eftimiades, a veteran of both CIA and DIA who’s long warned of Chinese cyberespionage and sabotage, had high praise for the executive order. But even he had unanswered questions about its actual execution.

The order as written is near perfect, he told me. The only shortfall is that the next president could overturn it with the stroke of a pen. “It absolutely has to go into law. The Congress must step up here,” he said. “The Chinese are very patient and they will easily wait out this administration.”

Nick Eftimiades

Should a law call out Huawei and other companies by name, as the Executive Order does not? No, Eftimiades said, and the draft bills now circulating on Capitol Hill are deliberately written in general terms. That’s simply “good tactics,” he said, because it gives the administration much-needed flexibility to pick its battles. For example, the US can now use the threat of a ban to pressure borderline cases into better behavior, something it could do with a rigid, pre-written list of targets.

Should a law call out Huawei and other companies by name, as the Executive Order does not? No, Eftimiades said, and the draft bills now circulating on Capitol Hill are deliberately written in general terms. That’s simply “good tactics,” he said, because it gives the administration much-needed flexibility to pick its battles. For example, the US can now use the threat of a ban to pressure borderline cases into better behavior, something it could do with a rigid, pre-written list of targets.

Having flexibility is particularly important for negotiations to come between the US and its allies as it tries to get them to follow its lead in restricting Chinese tech. “I think they’re going to find some face saving ways out,” Eftimiades said of the allies, “but negotiations are going to be quite intense” — especially if Washington threatens not to share intelligence with allies whose networks it considers insecure.

All told, Eftimiades said, the document gives President Trump powerful tools to act against not only Huawei but many other suspect Chinese firms on the foreign entities List, like ZTE. “I think all of those companies are going to banned, even if they pay a fine and they come off [the] list,” he told me. “I would hope they’d be banned.”

“Going by the words on the paper, I would say Huawei‘s pretty far down the road [to being banned], but, with this president, I can’t guarantee,” Eftimiades said. “It could be the grandest of negotiating tactics.”

Colin contributed to this story.

No comments:

Post a Comment