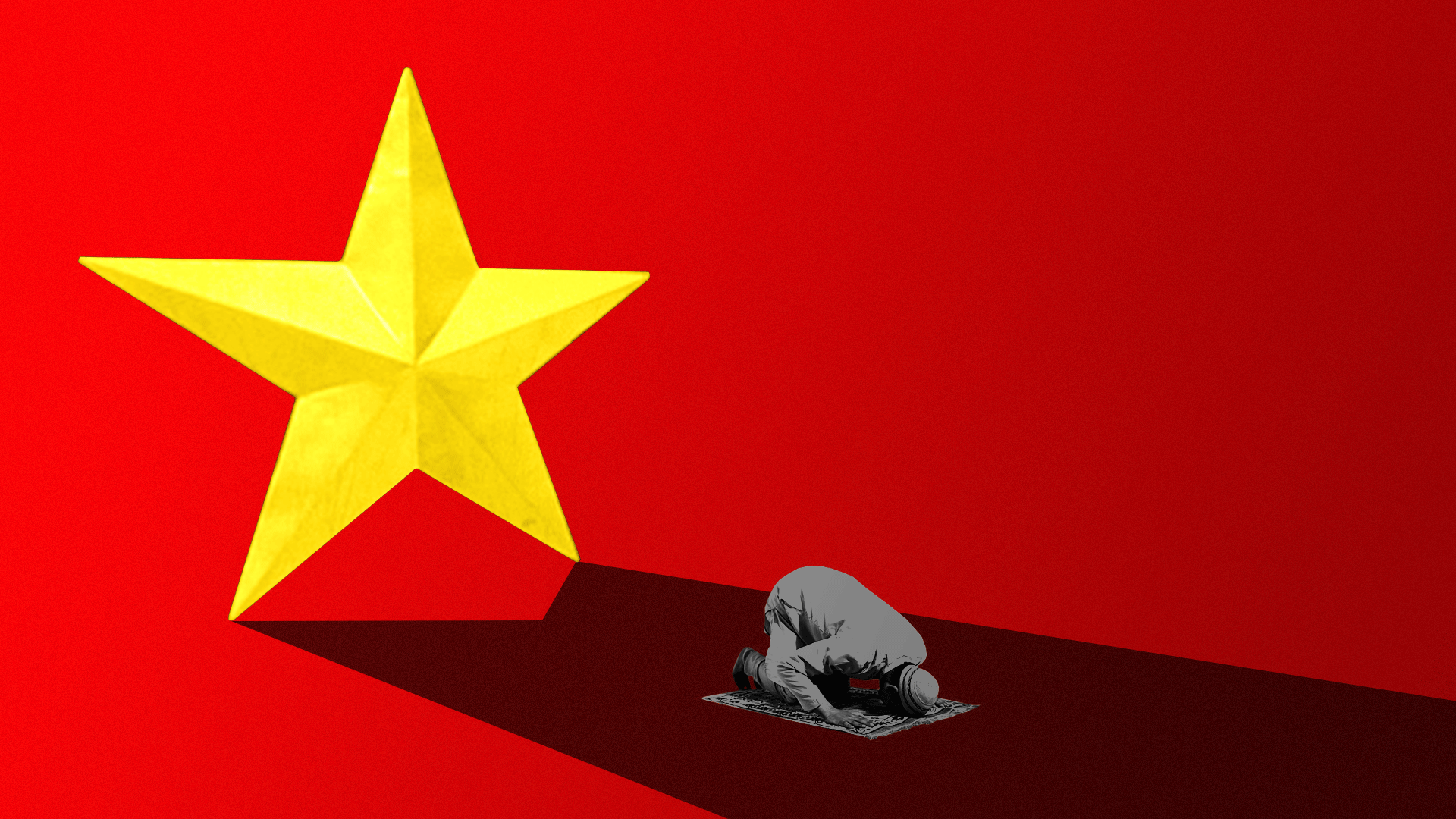

China has detained an estimated 1 million to 2 million Uighur Muslims in the region of Xinjiang, and millions more live one step away from detention under the watchful eye of the Chinese Communist Party.

China has detained an estimated 1 million to 2 million Uighur Muslims in the region of Xinjiang, and millions more live one step away from detention under the watchful eye of the Chinese Communist Party.

Why it matters: It has been two years since the internment camps first came to light internationally, and a series of reports from Xinjiang have made vivid the scale of the abuses. Yet foreign governments and corporations are content to pretend it isn't happening.

"If right now, just about any other country in the world was found to be detaining over 1 million Muslims of a certain ethnicity, you can bet we’d be seeing an international outcry," says Sophie Richardson, china director for Human Rights Watch.

"Because it's China, which has enormous power in international institutions these days, it's hard to muster any response at all."

"There has been this almost childlike hope that as China gets wealthier and more secure it would change" and adapt to international norms, Richardson says. Instead, China is using its economic clout and influence at the UN to undermine those norms.

China has long waged a campaign of "assimilation and cultural destruction" in Xinjiang, but under President Xi Jinping it has "dramatically escalated," says Omer Kanat, a prominent Uighur activist. "The camps are designed to eradicate the Uighur's religious and ethnic identity once and for all."

China used to deny the camps existed; it now claims they're voluntary and designed to root out extremism.

But a new Human Rights Watch report reveals Chinese authorities use an app to track nearly every aspect of Uighurs' lives and deem activities that have nothing to do with terrorism — keeping to oneself, using too much electricity, donating to a mosque — suspicious.

"These dubious criteria are being used to identify large numbers of people, many of whom are then arbitrarily locked up," Richardson tells Axios.

Even those who aren't locked up live under constant surveillance, as a recent NY Times interactive demonstrates.

What they're saying:

Prime Minister Imran Khan of Pakistan, which borders Xinjiang but has a deep economic reliance on China, told the FT in March: "Frankly, I don't know much about" what’s happening to the Uighurs.

Indonesian President Joko Widodo gave a similar answer, despite leading the world's largest majority-Muslim country.

UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres appeared to tiptoe around the issue on a visit to China last week.

Meanwhile the CEO of Volkswagen, which has a factory in Xinjiang, claimed last month that he was "not aware" of the mass detentions.

The Organization of Islamic Cooperation went so far as to praise China in March for "providing care to its Muslim citizens," while in February Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman defended China's "right" to crack down on its Muslim citizens "for its national security."

The U.S. and EU have spoken out, as has Turkey, but as a Council on Foreign Relations report points out, "no country has taken action beyond issuing critical statements."

Between the lines: "This is a difficult issue to address precisely because China has the world's second-largest economy" and is "ruthless" when challenged, says John Herbst, a former longtime diplomat now at the Atlantic Council. "Countries are not going to make this a critical issue in their relations with China."

What to watch: "What's happening in Xinjiang now didn’t happen overnight," Richardson says. "If analysts like us didn't see this coming — and I freely admit we didn't — I wonder what we're missing that’s coming next."

Trump's next moves to tank the Iranian economy

The Trump administration plans to target a new sector of the Iranian economy with significant new sanctions this week, two senior administration officials told me, speaking anonymously because they were not authorized to reveal the new sanctions. The officials would not say what sector the administration will target, but it won't be the energy sector.

Driving the news: The administration will likely announce this new wave of sanctions on Wednesday — marking the one year anniversary of President Trump's withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal.

The Wall Street Journal reported last week that new sanctions would target petrochemical sales. I'm told the administration will likely impose those sanctions soon, but the new sanctions planned for this week will target a different sector of the Iranian economy.

Why this matters: The Trump administration has been working to starve the Iranian regime of cash. But the administration is also trying to chill Iran's growth prospects by limiting the diversification of its economy, senior officials tell me.

Between the lines: Trump officials point to three possible outcomes of these efforts:

The cash-strapped Iranian regime comes back to the negotiation table to offer the U.S. a more favorable nuclear deal (no sign of this happening).

The regime hangs tight, but with far less money — in and of itself a good thing, in Trump's view. Iran's leaders will be forced to decide how to spend dwindling revenues, especially as flash floods and desert locusts besiege the Iranian countryside.

The Iran regime collapses. National security adviser John Bolton has long hoped for "the overthrow of the mullahs' regime in Tehran," though the Trump administration claims its official policy is not regime change.

The big picture: As we recently detailed, Iran's economy has been in free-fall since Trump withdrew the U.S. from the Iran nuclear deal and reimposed strict sanctions.

Iran's currency has plummeted, and dozens of European businesses have pulled out. The International Monetary Fund and the World Bank have issued dire forecasts for Iran's economy.

Iran also suffers from a fall in foreign direct investment. A senior administration official who receives updates on Iranian investment told me the country signed one foreign investment contract between January and March — "a deal with a Chinese company to build a petrochemical plant in Khuzestan."

What's next? Both officials said the regime could respond in a way that is "highly unpredictable" — diplo-speak for violent.

"So we are extremely mindful of security here at home," one added.

Trump's maximum pressure campaign hammers Iranian economy

An Iraqi peddler holds in his hand banknotes of Iranian rials for exchange in the Iraqi capital Baghdad. Photo credit Ahmad Al-Rubaye/AFP/Getty Images

Iran's economy has been in free-fall since President Trump withdrew the U.S. from the Iran nuclear deal and reimposed strict sanctions on its government. And the administration's unprecedented move on Monday designating the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) as a foreign terrorist organization is expected to further damage its economy.

The impact: The International Monetary Fund forecast an even deeper recession for Iran in its World Economic Outlook, released Tuesday. The IMF said it now expects Iran's economy to contract by 6% this year, compared to October's prediction of a 3.6% drop.

The World Bank predicted in an April report that the Iranian economy would "contract sharply," and it expects GDP to shrink by 3.8% in 2019 on the back of U.S. sanctions.

Dozens of European businesses have pulled out of Iran in the wake of the U.S. escalating its pressure campaign. "If you're the general counsel of an Asian bank or a European bank, your world changed when that designation came out yesterday,” Sec. of State Mike Pompeo said of the IRGC move. (Trump's ambassador to Germany, Ric Grenell, has been especially aggressive in pushing European companies to cut ties with Iran.)

Iran's currency, the rial, lost more than 60% of its value compared to the U.S. dollar last year, and inflation surged fourfold to an estimated rate of more than 40% by the end of 2018. (In 2019, the Central Bank of Iran has stopped publishing inflation data, leading some analysts to believe that the rate has kept rising beyond 40%.)

The big picture: "Our sanctions have denied the regime many billions in revenue that it would otherwise spend on terrorism, missile proliferation, and proxies," said Brian Hook, who helms Iran policy at the State Department. "The positive effects are increasingly visible. We will continue to use all the tools at our disposal to press the regime to change its destructive policies."

Yes, but: Iran's leaders have shown no signs, so far, that they're willing to concede an inch to the Americans. Most analysts we've spoken to believe the regime can endure even greater stress than they've suffered to date, noting it outlasted long bouts of dire economic conditions since the early 1980s.

"While maximum pressure can cause maximum damage, Tehran's strategy has been to exercise maximum patience," said Behnam Ben Taleblu, a senior fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies. "Iran is in dire straits, but they may not mind suffering a little longer if they think their suffering could soon be vindicated."

"This kind of recession developing countries can handle," said Djavad Salehi-Isfahani of the Brookings Institution. "In terms of economic collapse, that is not on the horizon. But increased poverty, lower income, higher unemployment? Yes, those things are probably going to happen in the next 12 months. ... My prediction is they will try to weather it."

What's next: The administration faces a major decision next month. After withdrawing from the nuclear deal, the Trump administration let eight countries keep buying Iranian oil without facing U.S. sanctions. On May 2, the administration will have to decide whether to keep those waivers in place.

No comments:

Post a Comment