by Andrew S. Erickson

As Assistant Secretary of Defense for Indo-Pacific Security Affairs Randall G. Schriver emphasized in his rollout remarks on May 2, 2019, “our annual report to Congress, which we refer to as the China Military Power Report… is our authoritative statement on how we view developments in the Chinese military, as well as how that integrates with our overall strategy.”

As Assistant Secretary of Defense for Indo-Pacific Security Affairs Randall G. Schriver emphasized in his rollout remarks on May 2, 2019, “our annual report to Congress, which we refer to as the China Military Power Report… is our authoritative statement on how we view developments in the Chinese military, as well as how that integrates with our overall strategy.”

Weighing in at a hefty 123 pages, this year’s document is nearly an inch thick. In terms of substance, it compares favorably among its seventeen predecessors. Among the report’s greatest strengths: as with previous iterations, it offers new data points and clarifications available nowhere else in authoritative form. This underscores the power of the U.S. government to disclose some of its collected information and accompanying analysis, a power this author and others believe should be used far more frequently.

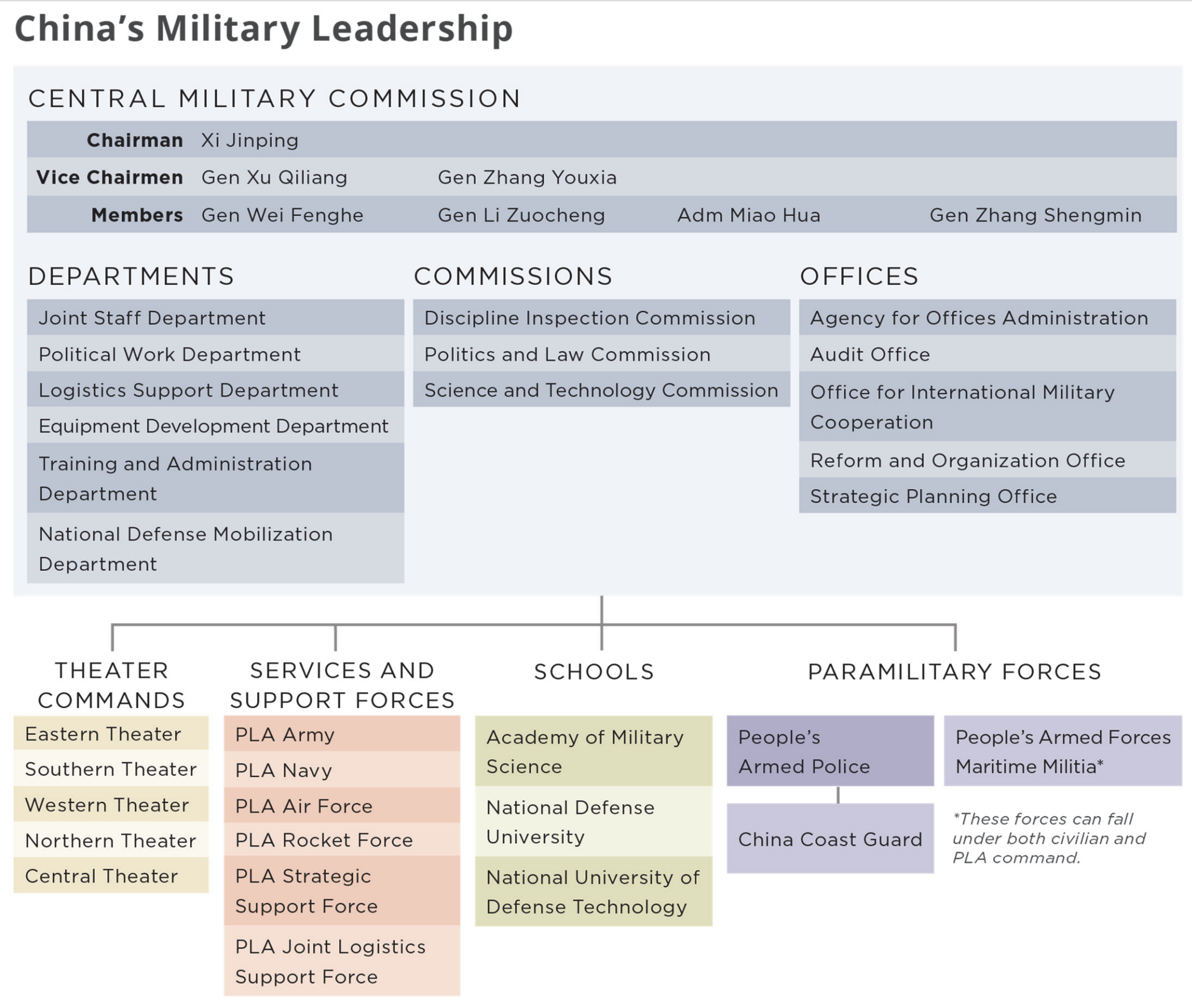

The report offers useful background throughout, with incremental updates. Pentagon releases are typically strong on concrete quantifiable details regarding force structure and technology, while rarely offering unique insights concerning abstract qualitative subjects such as the People’s Republic of China (PRC)’s strategic and doctrinal evolution. The history of this last topic, for instance, is covered well in such scholarly sources as M. Taylor Fravel’s new book Active Defense: China’s Military Strategy since 1949. Overall, however, the report rightly underscores that China under Xi Jinping is pursuing sweeping defense reforms as part of a comprehensive effort to make China a “strong country” with a “world-class military” by 2049. Xi himself has “called for more focused reforms of weapons procurement systems and other [civil-military integration] efforts to generate breakthroughs….” The Pentagon provides useful overviews of China’s Party-State-Armed Forces bureaucracy, including the current leadership of China’s obscure National Security Commission. The report’s delineation of China’s five Theater Commands and their respective assets and roles is particularly substantive and well-organized.

Special sections on PRC influence operations and Arctic efforts add useful focus, although they are concise to the point of being somewhat spare. “China in the Arctic” cites Danish concerns about Chinese “proposals to establish a research station in Greenland, establish a satellite ground station, renovate airports, and expand mining.” It also suggests possible future PLAN deployment of ballistic-missile submarines (SSBNs) to the Arctic Ocean. As Schriver emphasized, “whether or not that becomes an access point… safe harbor for strategic assets, such as ballistic-missile-carrying submarines, it is a possibility in the future and one we’ll watch very closely.”

In keeping with the Trump Administration’s outlook and priorities, there is greater emphasis on economic issues than in earlier years of the report. This year’s iteration highlights the U.S. Trade Representative’s conclusion that PRC government policies cause “harm to the U.S. economy of at least $50 billion per year.” Building on previous years’ analysis, the report judges that China’s defense budget grew an average of 8% inflation-adjusted from 2009-18. Beijing’s official military spending in 2018 was just over $170 billion; the Pentagon estimates actual spending at over $200 billion. As for revenue generation, China is currently in the top five of arms exporters globally, typically offering more flexible terms and creative side payments than competitors. Major deals with Pakistan and growing sales in the Middle East are bolstering order books. Armed UAVs are a major competitive advantage for China; most other would-be suppliers are bound by voluntary export control restrictions.

As an authoritative policy document, the report criticizes Beijing for its continued lack of transparency, including its failure to release a Defense White Paper since 2015. Notably, Schriver declared in his press briefing, “our concerns are significant when it comes to the ongoing repression in China. The Communist Party is using the security forces for mass imprisonment of Chinese Muslims in concentration camps.”

While the Pentagon chronicles many Chinese advances, it also acknowledges persistent weaknesses. As Schriver explains, “the report also suggests where they do need more work. …There are things that we do in terms of training, in terms of sophisticated integration of command and control… and intelligence, that they’re not quite there yet. The training is not as complex as ours.”

Maritime East Asia

This latest report continues a pattern of productive focus on the top-prioritized scenarios for People’s Liberation Army (PLA) preparation, including those concerning Taiwan and the South China Sea. It rightly points out that the PLA’s latest “military strategic guidelines” call for it to be prepared to fight and win “informatized local wars,” and to prevail in “maritime military struggle” that may span peacetime and wartime. It correctly concludes that “China expects significant elements of a modern conflict to occur at sea.”

The report devotes significant space to comparing PRC and Taiwan forces using a new methodology yielding substantially different numbers from previous years. It explains how rapid mainland military progress has rapidly eroded much the island’s technological and geographical advantages. For instance, China envisions and trains for a Joint Blockade Campaign designed to threaten Taiwan’s maritime and air access. Not only does it target Taiwan with a broad array of ballistic missiles, it even fields rocket artillery systems capable of spanning the Taiwan Strait, such as the PHL-03.

But the Pentagon is also frank about the PLA’s remaining limitations vis-à-vis its lead planning scenario. Seizure of small offshore islands is likely operationally feasible but would probably represent a Pyrrhic victory triggering international intervention far short of delivering control of the true prize: Taiwan proper, with its 23.5 million citizens and their free, democratic, Chinese-culture-infused society. While five Type 071 Yuzhao-class LPDs amphibious transport docks operational in the PLA Navy (PLAN) and three more are under construction/outfitting, the Pentagon judges that China has not launched enough amphibious warfare ships to optimally support relevant contingencies: “there is no indication that China is significantly expanding its landing ship force necessary for an amphibious assault on Taiwan.”

Regarding the South China Sea, the report draws linkages to key new pieces of hardware that may be particularly useful for that theater. These include the “world’s first large cargo UAV,” the AT-200, with 1.5 ton carrying capacity and ability to operate from “unimproved runways as short as 200 meters” including on small islands. Also relevant: the world’s largest seaplane, China’s AG-600. The report also underscores that China has deployed anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCMs) and surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) to the Spratlys in violation of Xi Jinping’s 2015 pledge not to militarize them.

Gray Zone:

The report pays proper attention to China’s emphasis on “gray zone” activities designed to fall below the threshold of armed conflict. Although the report also documents their use along China’s contested borders with India and Bhutan, such tactics are designed primarily to further disputed sovereignty claims regarding features and waters in the South and East China Seas (“Near Seas”). Here, China’s first sea force (the PLAN) often plays a backstop deterrence role over the horizon, while its second sea force (the China Coast Guard/CCG) and its third sea force (the People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia/PAFMM) operate on the front lines. The CCG is “by far the largest coast guard force in the world.” It has “the ability to intimidate local, non-Chinese fishing boats, as occurred in an October 2016 incident near Scarborough Reef. The PAFMM is approximated only by Vietnam’s maritime militia, which is no match for it. On a related note, under the Joint Logistics Support Force, “The PLA is integrating civilian-controlled support equipment, including ships… into military operations and exercises.”

Since it first included coverage of the PAFMM in 2017, the Pentagon’s annual report has authoritatively showcased substantive details concerning this formerly under-considered force. This year, for the first time, the report includes both the CCG and PAFMM in an organizational chart depicting the leadership and chain of command of China’s armed forces. A dedicated section highlights increasing coordination and interoperability among China’s three sea forces, propelled by recent reforms including the CCG’s subordination to the People’s Armed Police (PAP), itself now under the sole command and control of the Central Military Commission. Notably, China’s three sea forces have shown greater interoperability amongst themselves than have the PAP and PLA between themselves.

Taken together, these developments could enhance the ability of China’s second and third sea forces “to provide support to PLA operations under the command of the joint theater commands.” In the South China Sea, the report stresses, “the PAFMM plays a major role in coercive activities to achieve China’s political goals without fighting….” It “has played significant roles in a number of military campaigns and coercive incidentsover the years.” Of particular significance, “a large number of PAFMM vessels train with and assist the PLAN and CCG in tasks such as safeguarding maritime claims, surveillance and reconnaissance, fisheries protection, logistic support, and search and rescue.” Moreover, “In conflict, China may… employ CCG and PAFMM ships to support military operations.” This all makes it crystal clear that Chinese navy interlocutors cannot plausibly profess ignorance of the PAFMM to their foreign counterparts—as they have done repeatedly in official meetings. Based on the report’s nature and content, doing so profoundly insults American intelligence in all senses of the word.

No comments:

Post a Comment