Lily Kuo

Around this time of the year, the edge of the Taklamakan desert in far western China should be overflowing with people. For decades, every spring thousands of Uighur Muslims would converge on the Imam Asim shrine, a group of buildings and fences surrounding a small mud tomb believed to contain the remains of a holy warrior from the eighth century.

Around this time of the year, the edge of the Taklamakan desert in far western China should be overflowing with people. For decades, every spring thousands of Uighur Muslims would converge on the Imam Asim shrine, a group of buildings and fences surrounding a small mud tomb believed to contain the remains of a holy warrior from the eighth century.

Pilgrims from across the Hotan oasis would come seeking healing, fertility, and absolution, trekking through the sand in the footsteps of those ahead of them. It was one of the largest shrine festivals in the region. People left offerings and tied pieces of cloth to branches, markers of their prayers.

Visiting a sacred shrine three times, it was believed, was as good as completing the hajj, a journey many in underdeveloped southern Xinjiangcould not afford.Before and after images of the Imam Asim Shrine. Credit: Digital Globe/ Planet Labs

But this year, the Imam Asim shrine is empty. Its mosque, khaniqah, a place for Sufi rituals, and other buildings have been torn down, leaving only the tomb. The offerings and flags have disappeared. Pilgrims no longer visit.

It is one of more than two dozen Islamic religious sites that have been partly or completely demolished in Xinjiang since 2016, according to an investigation by the Guardian and open-source journalism site Bellingcat that offers new evidence of large-scale mosque razing in the Chinese territory where rights groups say Muslim minorities suffer severe religious repression.

Using satellite imagery, the Guardian and Bellingcat open-source analyst Nick Waters checked the locations of 100 mosques and shrines identified by former residents, researchers, and crowdsourced mapping tools.

Out of 91 sites analysed, 31 mosques and two major shrines, including the Imam Asim complex and another site, suffered significant structural damage between 2016 and 2018.

Of those, 15 mosques and both shrines appear to have been completely or almost completely razed. The rest of the damaged mosques had gatehouses, domes, and minarets removed.

A further nine locations identified by former Xinjiang residents as mosques, but where buildings did not have obvious indicators of being a mosque such as minarets or domes, also appeared to have been destroyed.

China’s hi-tech war on its Muslim minority – podcast

Uprooted, broken, desecrated

In the name of containing religious extremism, China has overseen an intensifying state campaign of mass surveillance and policing of Muslim minorities — many of them Uighurs, a Turkic-speaking group that often have more in common with their Central Asian neighbours than their Han Chinese compatriots. Researchers say as many as 1.5 million Uighurs and other Muslims have been involuntarily sent to internment or re-education camps, claims that Beijing rejects.

Campaigners and researchers believe authorities have bulldozed hundreds, possibly thousands of mosques as part of the campaign. But a lack of records of these sites — many are small village mosques and shrines — difficulties police give journalists and researchers traveling independently in Xinjiang, and widespread surveillance of residents have made it difficult to confirm reports of their destruction.

The locations found by the Guardian and Bellingcat corroborate previous reports as well as signal a new escalation in the current security clampdown: the razing of shrines. While closed years ago, major shrines have not been previously reported as demolished. Researchers say the destruction of shrines that were once sites of mass pilgrimages, a key practice for Uighur Muslims, represent a new form of assault on their culture.

Three-way composite of Jafari Sadiq shrine. Photograph: Planet Labs

“The images of Imam Asim in ruins are quite shocking. For the more devoted pilgrims, they would be heartbreaking,” said Rian Thum, a historian of Islamat the University of Nottingham.

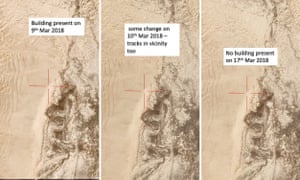

Before the crackdown, pilgrims also trekked 70km into the desert to reach the Jafari Sadiq shrine, honouring Jafari Sadiq, a holy warrior whose spirit was believed to have travelled to Xinjiang to help bring Islam to the region. The tomb, on a precipice in the desert, appears to have been torn down in March 2018. Buildings for housing the pilgrims in a nearby complex are also gone, according to satellite imagery captured this month.

Before and after imagery of the Jafari Sadiq shrine. L-R Dec 10 2013, April 20, 2019. Photograph:

“Nothing could say more clearly to the Uighurs that the Chinese state wants to uproot their culture and break their connection to the land than the desecration of their ancestors’ graves, the sacred shrines that are the landmarks of Uighur history,” said Thum.

“Nothing could say more clearly to the Uighurs that the Chinese state wants to uproot their culture and break their connection to the land than the desecration of their ancestors’ graves, the sacred shrines that are the landmarks of Uighur history,” said Thum.

‘When they grow up, this will be foreign to them’

The Kargilik mosque, at the centre of the old town of Kargilik in southern Xinjiang, was the largest mosque in the area. People from various villages gathered there every week. Visitors remember its tall towers, impressive entryway, and flowers and trees that formed an indoor garden.

The mosque, previously identified by online activist Shawn Zhang, appears to have been almost completely razed at some point in 2018, with its gatehouse and other buildings removed, according to satellite images analysed by the Guardian and Bellingcat.

Three locals, staff at nearby restaurants and a hotel, told the Guardian that the mosque had been torn down within the last half year. “It is gone. It was the biggest in Kargilik,” one restaurant worker said.Before and after images the Kargilik mosque. Credit: Digital Globe/ Planet Labs

Another major community mosque, the Yutian Aitika mosque near Hotan, appears to have been removed in March of last year. As the largest in its district, locals would gather here on Islamic festivals. The mosque’s history dates back to 1200.

Despite being included on a list of national historical and cultural sites, its gatehouse and other buildings were removed in late 2018, according to satellite images analysed by Zhang and confirmed by Waters. The demolished buildings were likely structures that had been renovated in the 1990s.

Two local residents who worked near the mosque, the owner of a hotel and a restaurant employee, told the Guardian the mosque had been torn down. One resident said she had heard the mosque would be rebuilt but smaller, to make room for new shops.

“Many mosques are gone. In the past, in every village like in Yutian county would have had one,” said a Han Chinese restaurant owner in Yutian, who estimated that as much as 80% had been torn down.

“Before, mosques were places for Muslims to pray, have social gatherings. In recent years, they were all cancelled. It’s not only in Yutian, but the whole Hotan area, It’s all the same … it’s all been corrected,” he said.

Activists say the destruction of these historical sites is a way to assimilate the next generation of Uighurs. According to former residents, most Uighurs in Xinjiang had already stopped going to mosques, which are often equipped with surveillance systems. Most require visitors to register their IDs. Mass shrine festivals like the one at Imam Asim had been stopped for years.

Removing the structures, critics said, would make it harder for young Uighurs growing up in China to remember their distinctive background.

“If the current generation, you take away their parents and on the other hand you destroy the cultural heritage that reminds them of their origin … when they grow up, this will be foreign to them,” said a former resident of Hotan, referring to the number of Uighurs believed detained in camps, many of them separated from their families for months, sometimes years.

Imam Asim shrine festival 2010. Photograph: Rian Thum

“Mosques being torn down is one of the few things we can see physically. What other things are happening that are hidden, that we don’t know about? That is what is scary,” he said.

“Mosques being torn down is one of the few things we can see physically. What other things are happening that are hidden, that we don’t know about? That is what is scary,” he said.

The ‘sinicisation’ of Islam

China denies allegations it targets Muslim minorities, constrains their religious and cultural practices, or sends them to re-education camps. In response to questions about razed mosques, foreign ministry spokesman Geng Shuang said he was “not aware of the situation mentioned”.

“China practices freedom of religion and firmly opposes and combats religious extremist thought… There are more than 20 million Muslims and more than 35,000 mosques in China. Religious believers can freely engage in religious activities according to the law,” he said in a faxed statement to the Guardian.

A demolished mosque in the old town of Kashgar, Xinjiang Uyghur autonomous region, China. Photograph: Eric Lafforgue/Art in All of Us/Corbis via Getty Images

But Beijing is open about its goal of “sinicising” religions like Islam and Christianity to better fit China’s “national conditions”. In January, China passed a five-year plan to “guide Islam to be compatible with socialism”. In a speech in late March, party secretary Chen Quanguo who has overseen the crackdown since 2016 said the government in Xinjiang must “improve the conditions of religious places to guide “religion and socialism to adapt to each other”.

Removing Islamic buildings or features is one way of doing that, according to researchers.

“The Islamic architecture of Xinjiang, closely related to Indian and Central Asian styles, puts on public display the region’s links to the wider Islamic world,” said David Brophy, a historian of Xinjiang at the University of Sydney. “Destroying this architecture serves to smooth the path for efforts to shape a new ‘sinicised’ Uighur Islam.”

Experts say the razing of religious sites marks a return to extreme practices not seen since the Cultural Revolution when mosques and shrines were burned, or in the 1950s when major shrines were turned into museums as a way to desacralise them.

Experts say the razing of religious sites marks a return to extreme practices not seen since the Cultural Revolution when mosques and shrines were burned, or in the 1950s when major shrines were turned into museums as a way to desacralise them.

Today, officials describe any changes to mosques as an effort to “improve” them. In Xinjiang, various policies to update the mosques include adding electricity, roads, news broadcasts, radios and televisions, “cultural bookstores,” and toilets. Another includes equipping mosques with computers, air conditioning units, and lockers.

“That is code to allow them to demolish places that they deem to be in the way of progress or unsafe, to progressively yet steadily try to eradicate many of the places of worship for Uighurs and Muslim minorities,” said James Leibold, an associate professor at La Trobe University focusing on ethnic relations.

Critics say authorities are trying to remove even the history of the shrines. Rahile Dawut, a prominent Uighur academic who documented shrines across Xinjiang, disappeared in 2017. Her former colleagues and relatives believe she has been detained because of her work preserving Uighur traditions.

Dawut said in an interview in 2012: “If one were to remove these … shrines, the Uighur people would lose contact with earth. They would no longer have a personal, cultural, and spiritual history. After a few years we would not have a memory of why we live here or where we belong.”

Since you're here…

… we have a small favour to ask. More people are reading and supporting our independent, investigative reporting than ever before. And unlike many news organisations, we have chosen an approach that allows us to keep our journalism accessible to all, regardless of where they live or what they can afford.

Readers’ support powers our work, giving our reporting impact and safeguarding our essential editorial independence. This means the responsibility of protecting independent journalism is shared, enabling us all to feel empowered to bring about real change in the world. Your support gives Guardian journalists the time, space and freedom to report with tenacity and rigor, to shed light where others won’t. It emboldens us to challenge authority and question the status quo. And by keeping all of our journalism free and open to all, we can foster inclusivity, diversity, make space for debate, inspire conversation – so more people, across the world, have access to accurate information with integrity at its heart.

The Guardian is editorially independent, meaning we set our own agenda. Our journalism is free from commercial bias and not influenced by billionaire owners, politicians or shareholders. No one edits our editor. No one steers our opinion. This is important as it enables us to give a voice to those less heard, challenge the powerful and hold them to account. It’s what makes us different to so many others in the media, at a time when factual, honest reporting is critical.

No comments:

Post a Comment