Brandon Morgan

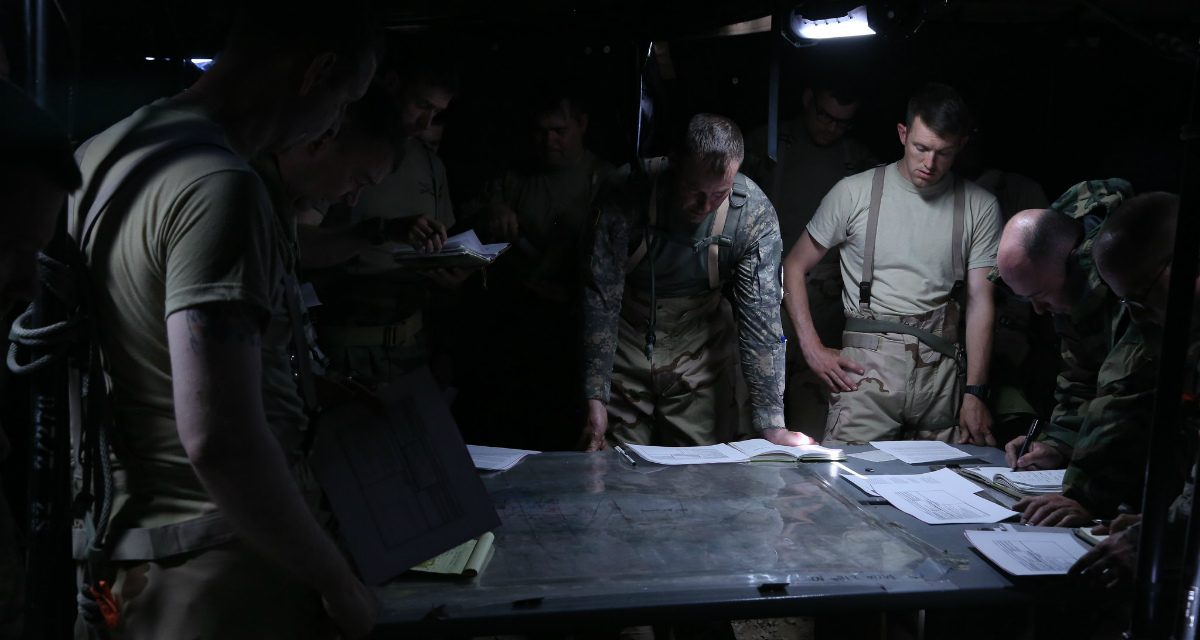

They are the crown jewels in the Army’s training and readiness program: the combat training centers. Every several weeks, a new brigade combat team arrives and prepares to go into “the box.” Soldiers, leaders, and equipment are tested, and units’ mission-essential tasks are validated in a challenging scenario that pits them against world-class opposing forces. While the exercise provides invaluable training with elements of joint cooperation, it is largely a ground-based, predictable fight, devoid of any political context—something that fails to reflect the way the Army envisions the future battlespace. The Army—and the joint force—must put the creative energy, collaboration, and funding into making scenarios at the combat training centers multi-domain and unpredictable—and introduce non-military dynamics like political contexts—in order to provide the most realistic battlefield operating environment for future conflict.

They are the crown jewels in the Army’s training and readiness program: the combat training centers. Every several weeks, a new brigade combat team arrives and prepares to go into “the box.” Soldiers, leaders, and equipment are tested, and units’ mission-essential tasks are validated in a challenging scenario that pits them against world-class opposing forces. While the exercise provides invaluable training with elements of joint cooperation, it is largely a ground-based, predictable fight, devoid of any political context—something that fails to reflect the way the Army envisions the future battlespace. The Army—and the joint force—must put the creative energy, collaboration, and funding into making scenarios at the combat training centers multi-domain and unpredictable—and introduce non-military dynamics like political contexts—in order to provide the most realistic battlefield operating environment for future conflict.

Multi-Domain

In the current structure of the Army’s combat training center rotations, Army units play out scenarios against a peer adversary with minimal involvement from the other branches of the joint fighting force, with joint participation typically limited to too-small complements of “unified action partners.”. But decisive action conflict faced by the Army of tomorrow will be characterized by the interwoven campaigns with the naval, air, cyber and space domains. To address this training gap, Navy and Air Force command and staff should be invited to plan and execute simulated naval and air campaigns against a peer enemy with highly lethal anti-access and area-denial capabilities. The outcomes of these naval and air engagements must have effects and repercussions across the multi-domain spectrum, to include on the Army ground forces participating in the DATE (decisive action training environment) rotation.

One can look back in history—even before the convergence of domains that the Army expects will increasingly characterize conflict—to see how battlefield outcomes in one domain led to major consequences in the others. In August 1942, during the Guadalcanal campaign, the Japanese naval forces’ crushing victory over the US Navy at Battle of the Savo Island led to US Marines going hungry by day for lack of naval resupply and Air Corps pilots at Henderson airfield ducking for cover by night against uncontested Japanese naval bombardment. Today, the joint force remains in a similarly tenuous situation, as Russianand Chinese ballistic missiles put US Navy bases at Guam, Air Force bases in the UK, and Army pre-positioned stocks in Europe in grave danger in the event of conflict.

As the Army and the joint force pivot toward decisive action against peer enemy threats, Army commanders and their soldiers must have an acute understanding of the effects of sea and air battles across the multi-domain spectrum. If the supply chain of ammunition, repair parts, and food were at severe risk from the beginning of conflict, leaders will become much more likely to enforce strict ammunition consumption limits, experiment with 3D repair part printing techniques, and learn where they can obtain their next meal. For the cyber and space domains, brigade maneuver planners must tie effects in each into the ground maneuver plan, which also must be synchronized with the naval and air campaigns through the use of a robust liaison network. Units must understand how to plan and synchronize the use of assets available across domains throughout the maneuver. The Army can begin to fully enhance this training opportunity by incorporating a space planner into the brigade combat team staff, and building space considerations into training scenarios. Doing so, along with increasing the involvement of other services, will endow each combat training center rotation with the characteristics of a multi-domain battlefield.

Unpredictable

Today’s combat training centers prioritize the efficiency of systematized scenario structures over realistic unpredictability. Offensive, defensive, counterattack, and all other phases of the exercise are largely fixed in time prior to the beginning of the exercise, which gives senior military leadership a predictable benchmark for unit performance but undermines the realistic context in which our forces will fight. Would US forces training with Baltic partner forces be given enough strategic warning to assemble, draw ammunition, and fight decisively if Russia exploits a future Zapad exercise? In November 1950, were US Army and Marine forces at the Chosin Reservoir, and more importantly, their commanding generals, given advance warning that they would need to cease their offensive operation north to the Yalu River and transition to a defensive retrograde when multiple Chinese divisions violently crashed into their assembly areas?

Combat training centers must add military unpredictability by reducing scripted phasing and introducing dynamic deployments of reinforcing elements for both the enemy and friendly forces. The opposing force should be capable of rapidly expanding to two brigades, either by increasing the number of permanently stationed soldiers or by incorporating a rapidly deployed stateside US unit. This would accomplish multiple training objectives, including dynamic deployment of high-readiness units and allowing the primary training brigade to defend at a ratio closer to 1:3. Additionally, additional US forces should be added to the friendly forces in the area of operations, stressing both the brigade already “in the box” and keeping the reinforcing units—from the 82nd Airborne or other rapid deployment forces—at high readiness, testing their ability to assemble, deploy, and fight at a moment’s notice. The Army has already tested this concept with an armored brigade rapidly deploying into pre-positioned equipment in Europe, and should do so at the National Training Center. Deployments of reinforcing units should occur only periodically and be unanticipated by the primary training brigade in order to fully simulate the political and military unpredictability of war. The force could also be pre-staged, with the primary training brigade not knowing whether it would be added as a friendly force or opposing force (or neither) until intelligence or reports from high headquarters report the new development. In either case, the brigade staff will be challenged to adapt to the unpredictability expected in a real-world future conflict.

Politically Dynamic

While today’s combat training rotations involve extensive allied partner participation in the military exercise, the scenarios do not thoroughly reflect the highly dynamic political context within which US forces will likely operate during future conflict. Uncertain political currents have been a staple of modern decisive-action warfare. Allied powers in World War I could not have predicted the grave military consequences of the Russian Revolution, which resulted in Russia’s withdrawal from the war in 1918 and allowed Germany to concentrate its forces on the Western Front. In World War II, Allied civilian and military leaders could not predict how Vichy French forces in North Africa would respond to Allied Landings—with welcome or resistance. When it turned out to be the latter, it had disastrous initial results for the landing force. In 1950, even after multiple warnings from the Indian ambassador, the United Nations stood bewildered at massive Chinese intervention in the Korean War.

Today, Western military and political leaders are struggling to understand the impacts of Ukraine’s recent decision to vote Volodymyr Zelensky, a former television comedian with no political experience, into the presidency. The conduct of war, politics, and foreign policy cannot be uncoupled, and for that reason US Army and partner units should conduct training rotations within a simulated but highly contested and dynamic political environment—with consequently unpredictable battlefield effects. Professional role players could play foreign diplomats and other non-military influential figures. Army foreign area officers would be tasked with establishing relationships and rapport, gathering intelligence, and briefing their diplomatic and military headquarters, whereby the information they provide would produce tangible effects on the battlefield. For example, a foreign area officer could learn that if US forces are able to secure certain border-crossing points, then the host nation will provide logistical and movement support. The possibilities are limitless, as are the training opportunities for brigades (and foreign area officers), as long as the political interplay enhances, rather than diminishes, the brigade’s mission-essential training tasks.

Today’s combat training centers are the Army’s premier training venue. However, senior military leadership could significantly improve their impact by taking several key steps to optimize their training value for the total force. Combat training centers must fully incorporate both simulated and live naval and air campaigns, interwoven with actively contested space and cyber domains, the outcomes of which create effects across all domains. These training rotations must become unpredictable and politically dynamic, allowing for creative scenarios to replicate complex policymaking at the international level with battlefield consequences throughout the exercise. These actions will challenge leaders and servicemembers throughout the joint force to think even more critically about the complexities of multi-domain operations, with improved readiness and future lethality as the end result.

No comments:

Post a Comment