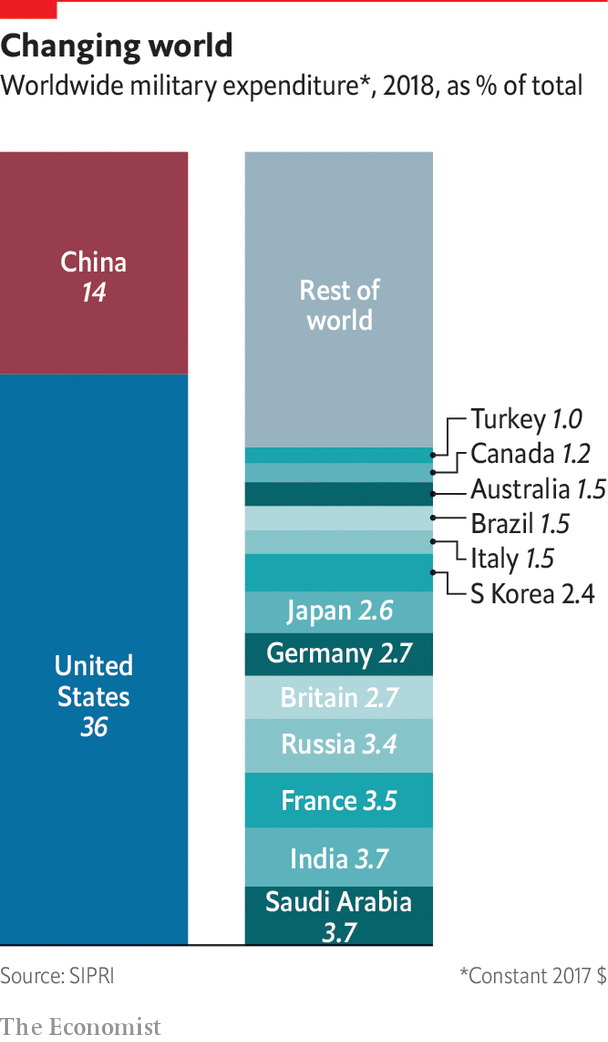

THE WORLD is arming itself to the teeth. That is the conclusion of a new report published on April 29th by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), a think-tank. Global military spending last year rose to $1.8trn, says SIPRI—the highest level in real terms since reliable records began in 1988, during the cold war, and 76% higher than in 1998, when the world was enjoying its “peace dividend”. Military spending as a share of global GDP has fallen in recent years, but that offers little reassurance in a world of rising geopolitical tension.

THE WORLD is arming itself to the teeth. That is the conclusion of a new report published on April 29th by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), a think-tank. Global military spending last year rose to $1.8trn, says SIPRI—the highest level in real terms since reliable records began in 1988, during the cold war, and 76% higher than in 1998, when the world was enjoying its “peace dividend”. Military spending as a share of global GDP has fallen in recent years, but that offers little reassurance in a world of rising geopolitical tension.

The spending boom is driven, above all, by the contest between America and China for primacy in Asia. Start with America. In 2018 it raised its already-gargantuan defence budget for the first time in seven years, ending an era of belt-tightening imposed by Congress. The boost reflected the Trump administration’s embrace of what it calls “great power competition” with Russia and China—requiring fancier, pricier weapons—in place of the inconclusive guerilla wars it had fought since 2001.

America’s military heft has no equal. Its outlay of $649bn (in 2017 dollars) was almost as large as the next eight countries combined, by SIPRI’s reckoning. Even that did not satiate the Pentagon’s appetite. It got $716bn this year (in current dollars, as counted by the Department of Defence) and hopes for a staggering $750bn in 2020—an annual increase larger than the defence budgets of almost all of its NATO allies. That includes nearly $10bn for cyber operations, a 10% year-on-year boost; over $14bn for space, a 15% jump; and the biggest budget request for shipbuilding in two decades.

China is far behind. It spends somewhere between a quarter and two-fifths of what America does (the precise amount is unclear, say experts, because Chinese spending is so opaque). Nor is its military expenditure growing at a 10% clip, as it did on average in the years between 2000 and 2016. But it has risen relentlessly for a quarter-century, completely changing the balance of power in Asia.

China is far behind. It spends somewhere between a quarter and two-fifths of what America does (the precise amount is unclear, say experts, because Chinese spending is so opaque). Nor is its military expenditure growing at a 10% clip, as it did on average in the years between 2000 and 2016. But it has risen relentlessly for a quarter-century, completely changing the balance of power in Asia.

Between 2009 and 2018, America’s defence spending fell by 17% in real terms whereas China’s grew by 83%—accelerating under President Xi Jinping and outpacing every other big power. “No one has ever presided over anywhere close to this level of Chinese military development in Chinese history before Xi,” notes Andrew Erickson, a professor at the US Naval War College. Its navy has been a particular beneficiary. Between 2014 and 2018, China launched naval vessels with a total tonnage exceeding that of the entire Indian or French navies, notes IISS, another think-tank. Even so, the country’s defence spending is still smaller as a proportion of GDP than that of any other top-five country: 1.9% to America's 3.2%. That means it has room to grow, should the geopolitical mood darken.

Military reforms that Mr Xi introduced in 2015, including a slimming down of the army and reorganisation of the command structure along American lines, are also likely to have given China more bang for its yuan.

In response, China’s regional rivals have opened their purses, too. India now outspends every European country. South Korea’s annual increase in 2018 was the highest since 2005. And Japanese spending is set to surge in the next five years, with new offensive weapons breaking old pacifist taboos. All in all, Asian military spending makes up 28% of the world’s total, up from 9% in 1988.

Meanwhile, Europeans, having hollowed out their armed forces after the cold war, are getting their act together. In 2018 NATO’s European allies raised military spending by 4.2% in real terms, according to IISS. Poland, which is particularly anxious about next-door Russia, boosted spending by 8.9%.

Were European spending to be lumped together, the continent would be the world’s second-largest military power, outspending Russia fourfold. In practice, Europe’s hodge-podge of duplicated, mismatched equipment (Europeans use 17 types of tanks to America’s one) and continued dependence on America in key areas—such as moving troops and refueling warplanes—mean that its armed forces are far less than the sum of their parts.

Yet not everywhere is piling up arms. Military spending in Africa shrank for a fourth consecutive year in 2018, by 8.4%, driven by big falls in Angola, Algeria and Sudan, says SIPRI. Protests in the latter two countries, with armies under pressure to hand over power to civilians, might cause bloated military budgets to be squeezed further.

The Middle East also seems to be cooling off after years of frenzied arms-buying. Though SIPRI lacks data for Qatar and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), two of the biggest customers for Western arms companies, and for war-torn Yemen and Syria, spending in the rest of the region fell by 1.9% in 2018.

That trend seems likely to continue. Saudi Arabia, the region’s biggest fish, which sets aside a huge 8.8% of GDP for defence, will slash its military spending by 9.1% this year. Iran, its rival, plans even bigger cuts of its own—though the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), which has done most of the recent fighting in places like Syria, got a hefty raise, as did the intelligence ministry, which has been bumping off dissidents abroad.

The most interesting contraction is, however, in Russia. “Can they count?” President Vladimir Putin asked of his Western rivals in February. “I'm sure they can. Let them count the speed and the range of the weapons systems we are developing”. But despite the theatrical flaunting of new missiles, and NATO’s impressive rearmament to the west, SIPRI calculates that Russia’s defence budget actually shrank by 3.5% in 2018—putting it outside the top five for the first time in over a decade. This may be the result of a weakening rouble. But Russia’s long military spending spree seems to be drawing to a close. That is a sobering thought for Mr Putin.

No comments:

Post a Comment