Kerry Brown

They also made it clear that, as with so many other things in the UK, the decision seemed to have been made in solitude by Prime Minister Theresa May. This will probably be the basis for interesting discussions when the almost simultaneously announced state visit of US President Donald Trump takes place in early June.

They also made it clear that, as with so many other things in the UK, the decision seemed to have been made in solitude by Prime Minister Theresa May. This will probably be the basis for interesting discussions when the almost simultaneously announced state visit of US President Donald Trump takes place in early June.

The US has made it clear in word and deed that Huawei

concerns it, but it has

no company that can supply what Huawei offers. In many ways, in terms of price at least, Huawei has few competitors.

For a UK looking at lean growth in the years of being out of the EU – if and when

that happens (it has already been delayed twice, and is now set for the end of October this year) – price becomes increasingly important.

This is one of the realities of the UK in the era of what politicians once declared would be that of “Global Britain”.

For all the grand rhetoric, the reality for the foreseeable future is that the UK’s horizons and its options are going to narrow as it seeks to range free from its prime economic partnerships within the European Union.

There is nothing sui generis about the UK’s position with regards to China. Throughout Asia, into Latin America and Africa, the challenge is the same – how to balance security interests that link closely with the US or other partners, and the emerging economic benefits that come from working more with China.

Chinese investment in the UK is minimal – less than 1 per cent of current stocks. For most British people, too, their passions and ire seem to be directed at the EU. In the current context, China seems remote and engagement with it something reserved for the specialists.

This will need to change, and Huawei is introducing British policymakers at every level to a world that is transforming before their eyes.

China is no longer the supplicant it was in the past – smaller and marginal, and of modest importance to British interests.

Now it is starting to emerge as the most likely contender to replace those more established economic relationships now blighted by entwinement with the EU.

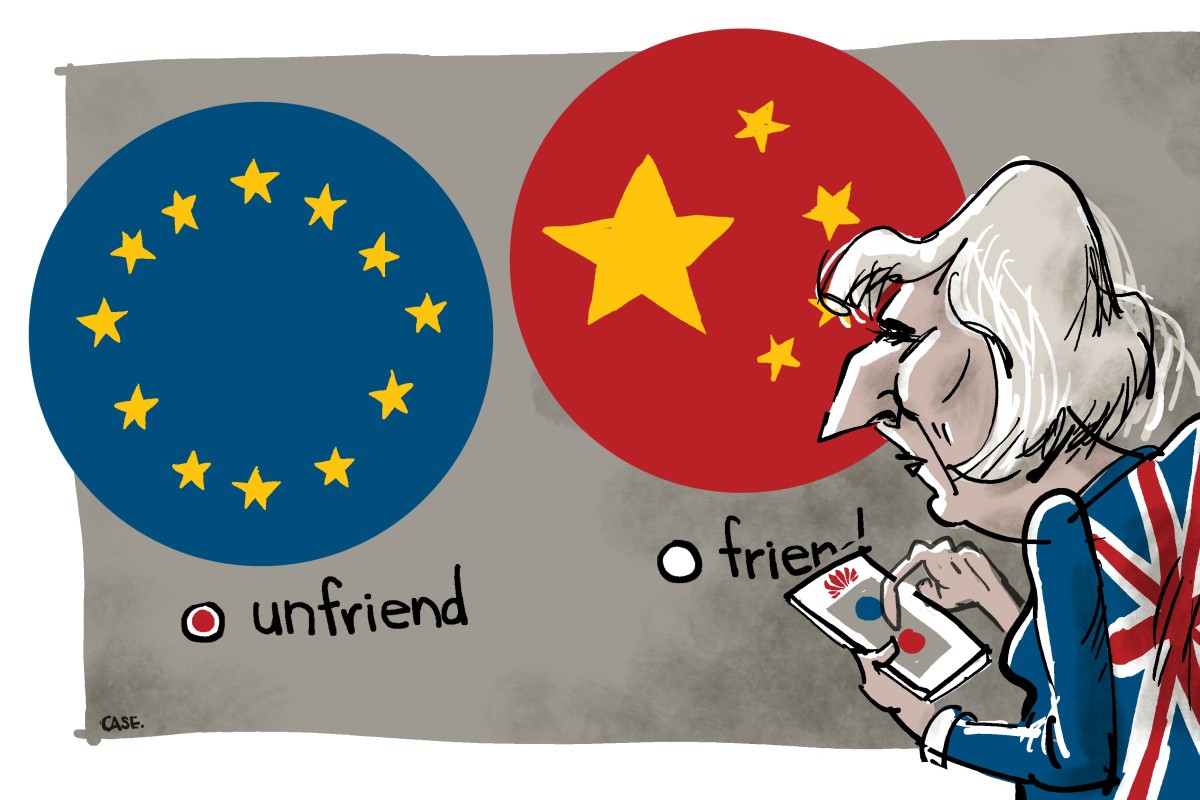

The unfriendly message the UK sent in the referendum in June 2016 means that the friendliness now needs to be extended to a partner the UK has never really had to deal with on any great scale before.

Dealing with the Hong Kong handover and colonial entanglements of the past were the preserve of a British political, academic and business elite.

The 300 graduates in Chinese studies that Britain produced each year were more than sufficient to service this need. Now everyone after a fashion needs to become a China expert in the UK.

An issue like Huawei shows precisely how China is moving to a far more central place in British interests, and starting to pose much more searching questions for everyone, not just specialists.

Huawei is a huge potential investor, with a site

already earmarked in Cambridge for a major research centre. It is becoming a significant employer.

The UK, as former intelligence officials attest, knows Huawei better than most through a centre set up to test Huawei technology for any security issues. No one else has this.

Clearly, all this shows that the UK figures in Huawei’s strategic calculations. Of all developed economies, it is now in position to be most open-minded and amenable to Chinese partners like this.

In essence, the Huawei case is symptomatic of the great opportunity, and the great risk, of the current moment for the UK as it looks at what to do with China

On the positive side, it has the chance to think in a different way about a partner it once gave little real attention to.

In the years when German chancellors and French presidents were making almost annual visits to Beijing, Tony Blair, Gordon Brown, David Cameron and then Theresa May seemed to want to avoid the place. May’s first visit was on becoming prime minister.

Engaging with Huawei is likely to turn out as a series of lessons for the UK as it seeks to accelerate its learning curve over China.

Officials might wish to acquaint themselves with a saying attributed to Confucius: “There are three ways to learn: by reflection, which is noblest; by imitation, which is easiest; and by experience, which is the bitterest.”

The simple fact is that the UK has left little time for reflection and is apparently seeking not to imitate the US, the rest of the EU and its allies. Experience looks likely to be London’s chosen wrote.

The attribution of the saying to Confucius may well be erroneous. Let’s hope the sentiments are too, and the UK can show the world that deeper linkages with China are largely positive experiences, not ones that leave a bitter residue.

No comments:

Post a Comment