By Kori Schake

Hastings Ismay, NATO’s first Secretary General, said the Alliance’s purpose was “to keep the Soviet Union out, the Americans in, and the Germans down”. In this article, Kori Schake and Erica Pepe explain how NATO has succeeded at the first two of these aims and failed at the third by instead rehabilitating Germany. They also write that despite the current threats emanating from China, Russia and populism within Alliance member states, most NATO statesmen of the past would gladly trade their problems for those of today.

Hastings Ismay, NATO’s first Secretary General, said the Alliance’s purpose was “to keep the Soviet Union out, the Americans in, and the Germans down”. In this article, Kori Schake and Erica Pepe explain how NATO has succeeded at the first two of these aims and failed at the third by instead rehabilitating Germany. They also write that despite the current threats emanating from China, Russia and populism within Alliance member states, most NATO statesmen of the past would gladly trade their problems for those of today.

This article was originally published by the NATO Defense College (NDC) in April 2019. Image courtesy of the Imperial War Museums, © IWM (A 30046).

Lord Hastings Lionel Ismay, NATO’s first Secretary General, famously said the purpose of the Alliance was “to keep the Soviet Union out, the Americans in, and the Germans down”.1 Across its seventy years, NATO has succeeded at the first two, and gloriously failed at the third, instead rehabilitating Germany as an anchor of liberal values and a major military power webbed closely into cooperation with like-minded countries.

As we are currently experiencing, all three of those elements are hard-won successes, and have to be won over and over. That is not a failing or a danger, it is the simple fact of reaching and sustaining agreement among sovereign states, facing grave and changing threats across time. As the American poet Walt Whitman wrote, “must not Nature be persuaded many times?”2

That NATO has proven so malleable as circumstances change is a great tribute to the statesmen and soldiers who have stood its helm across the 70 years. It is also a frank acknowledgement that the NATO Allies believe we continue to need each other’s help to make our countries secure.

The Russians out

For the United States, the Soviet threat of conquest was always the animating purpose for NATO, organizing Europe was always the mean of achieving that goal. The Soviet intention to both subjugate and penalize the territories it wrested from Nazi Germany in World War II was clear enough, in August of 1945 that Harry Truman weighted the signal it would send the Soviets in his decision to drop the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Soviet domination of Eastern Europe then cast a long shadow into Western Europe, and even across the Atlantic. If there had been no threat of Soviet aggression, there would have been no NATO. If the Soviets had not been seen as an insidious threat to free societies, the Marshall Plan and Truman Doctrine would never have been developed. If the Soviet military threat were not judged existential, NATO would not have created an integrated military command structure, and built the Federal Republic of Germany’s Bundeswehr. If Soviet expansion to NATO’s south had not alarmed Allies, NATO would not have admitted Greece and Turkey in the early 1950s. If the quantity of Soviet conventional forces were not so overwhelming, NATO would not have embraced nuclear deterrence or developed innovative military technologies that enabled operational concepts like the 1980s’ follow-on-forces attack. If the Soviet “peace policy” of the mid-1950s were not so tempting to Western publics, NATO would not have gotten into the arms control business. If Russia had not taken that aggressive path in Ukraine in recent years, NATO would not have expanded to include new members, built new competencies like the NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence, or deployed forces onto the territory of Poland and the Baltic States (as per decision at the Warsaw NATO Summit, 8-9 July 2016).

Russia under Vladimir Putin has tried to characterize NATO as a threat; that is only conceivable in the context of a Russia that seeks weak, fractured, intimidated countries on its borders. What NATO offered Russia at the end of the Cold War was inclusion on equal terms into the European order, provided that Russia respected the independence of sovereign states to choose their relationships. Russia’s desire to dictate the terms of other countries’ allegiances is what collapsed hopes for a different relationship between NATO and Russia.

Russia now seeks to subvert the power of the West, using the openness of NATO Allies as weapons against their domestic vibrancy and Allied solidarity. This poses an enormous challenge for the countries of the Alliance. The surprise is not that Russia is seeking to undermine Alliance cohesion, or that Allies have to be rallied to common purpose, but that Alliance solidarity is so durable in the face of Russian subterfuge.

The Americans in

When the Truman Administration entered into negotiations with Canada, Britain, France and the other Brussels Treaty signatories3 about an alliance to stabilize post-war Europe, it was reluctant to contemplate an extensive US military involvement in the protection of Europe.4 The Washington Treaty establishing NATO not only limited the geographic scope of the Alliance, but also left generous ambiguity about what states were actually committed to in the event of an attack. The Organization’s Article 6 circumscribes the Treaty area to Europe and North America, excluding most of the then-colonial holdings of Britain and France, which the US feared being dragged into protecting. So it is a heavy irony that the United States has been the motive force in pulling NATO “out of area”. NATO’s Article 5 reads that “an armed attack against one or more of them in Europe or North America shall be considered an attack against them all” but requires member states only to take action “as it deems necessary, including the use of armed force.”

The liberal international order, that the US and its Allies created from the ashes of World War II, was less a design of grand strategy than a grudging, step by step experimentation with the minimum it would take to cement cooperation adequate to prevent Soviet domination of Europe. Initially, the US hoped the Treaty would suffice. Alarm at the cataclysm of the Korean War convinced the Allies that political coordination needed to be undergirded by military preparations, and so an integrated military command, the Allied Command Europe and its headquarters, the Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe (SHAPE), was added onto the Alliance in 1951.

Military integration was acknowledged impossible without American participation, given the still destitute state of most European allies. When General Dwight Eisenhower testified to Congress in favour of stationing US troops in Europe, on 1-2 February 1951, he advocated it for a limited time, just until European nations regained their strength and could field sufficiently powerful military forces to counter the Soviet threat.5

The cost in American lives defending Europe against the Soviet threat was a constant source of friction throughout the Cold War, revealed most clearly in debates about nuclear strategy. Since the first NATO strategy document of December 1949,6 Allies have put emphasis on pursuing the maximum efficiency with the minimum necessary expenditures of manpower, money and materials. In order to gain greater effectiveness from a limited military budget, the Eisenhower Administration shifted principal reliance onto nuclear weapons, something Europeans accepted only as the alternative to American abandonment.

American desire to reduce the costs of securing Europe led the “new look” policy of utilizing tactical nuclear weapons to substitute for conventional forces. The new approach was integrated into the NATO strategic document MC 48, of November 1954, which explicitly stated that the superiority in atomic weapons had become the most important factor in a major war; an idea successively reinforced by the Overall Strategic Concept MC 14/2, of May 1957, which placed heavy emphasis upon the use of nuclear weapons. Fear of a nuclear exchange with the Soviet Union once they had intercontinental delivery systems, with the launch of Sputnik, in November 1957, led the US to push a strategy of “flexible response” that raised the threshold of nuclear use. Europeans fretted about American efforts to shift the burden of fighting the Soviet Union onto European forces and territory.

Only in January 1968, the Alliance reached consensus for the approval of a new Strategic Concept (MC 14/3), introducing a more flexible nuclear strategy and the notion of escalation, which precipitated France’s withdrawal from the military command and remains in effect. In fact, burden-sharing has been as central to NATO as has the first Soviet, then, Russian threat. The Mansfield Amendments of the early 1970s, which called for a 50 percent reduction in the number of US troops deployed in Europe, assuming that Allies should have made more efforts to assume the burden of their own defence, conveyed American exasperation that NATO Allies did not judge the Vietnam war as a war for Western values. That exasperation has only increased as America’s European Allies grew more prosperous – President Trump may be ruder and more transactional than his predecessors, but they shared his view that Europe had shifted a disproportionate burden of its own defence onto American shoulders.

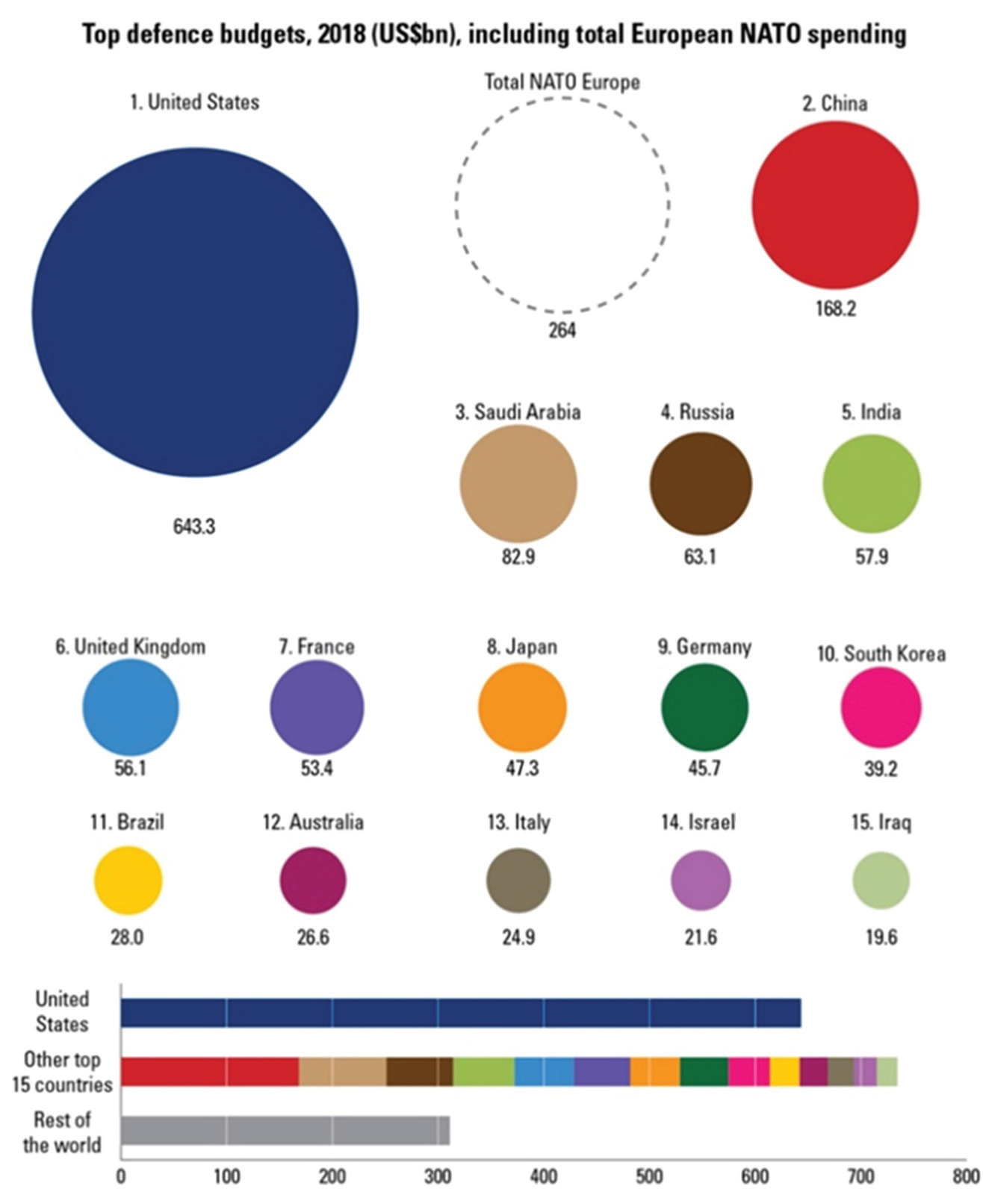

As IISS data shows, the US spends USD35 billion of its USD643 billion defence budget directly on European defence, more than the total defence spending of any NATO country other than Britain, France, and Germany (see graph on this page). In order to reach the target of 2 percent of GDP, European allies would need to find an extra USD102 billion on top of their current defence spending.7 As the former US Secretary of Defense, James Mattis, plaintively put it at the NATO Defence Ministerial meeting in February 2017, “Americans cannot care more for your children’s future security than you do”.

The Germans down

Catherine Kelleher, the author of Germany and the Politics of Nuclear Weapons has said that in 1945, “it wasn’t clear who Germany’s friends were; but if you picked your friends, it became clear who your enemies were”. By 1949, with Soviet pressure on Four Power rights in Berlin contrasting with more liberal policies by the Western occupying powers in Germany, the part of Germany that got to choose tacked West. Extravagant efforts by the West, and particularly Americans, to sustain Berlin through the 1948-1949 Soviet blockade rewarded the westward orientation of Germans in the zones of occupation.

It did not cement West Germany or other European states wracked by wartime devastation in the West, however. One of NATO’s central challenges has always been how to keep West Germany voluntarily allied with the West, rather than becoming neutral. What a unified Germany has become is the moral centre of gravity of the NATO Alliance. It is Germany that thinks most carefully about the ethical challenges. It is Germany whose participation in military operations provides the broadest validation for other Western powers. It is Germany who challenges the fear of free societies about terrorism emanating from migrants. It is Germany who, alongside the other NATO Allies, invoked Article 5 for the first time in 2001 when the United States was attacked. And it is Germany who tentatively committed troops to the mission in Afghanistan and have stood alongside the US and other NATO Allies there for nearly two decades. Surely it is the greatest achievement of the NATO Alliance that a reformed Germany has become the ethical bellwether of Europe where using military force is concerned.

Current and future challenges

Another part of NATO’s genius has been sincerely committing to contradictory principles. The apogee of this impressive quality was the Harmel Report of 1967, which cemented Alliance commitment to nuclear weapons as their ultimate protection while also advocating their elimination. The so-called “dual- track” decision of deterrence and détente allowed NATO to build its military strength while sustaining both allied cohesion and popular support. It is the model for how free societies band together and manage disagreements. NATO nuclear deterrence, a core element of the Alliance collective defence since the foundation, changed over the years but continued to play a critical role in NATO’s defence posture even after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, as shown in the three post-Cold War Alliance’s Strategic Concepts in 1991, 1999, and 2010.

Our challenge has always been how to create and sustain cohesion of the West. It was the hardest part of NATO’s work, and it remains so.

Our current problems – Russia developing tools to undercut democracy in Western states, a rising China surreptitiously buying in to European infrastructure for intelligence purposes, the US recklessly challenging the liberal order, populism within our own countries because of rapid technological innovation and economic dislocation, terrorism, brutality in adjacent areas that create migrancy, are unquestionably daunting. But we should not lose sight that they are easier than the challenges NATO’s founders and our predecessors faced. We ought not talk ourselves into believing protecting our societies is too burdensome.

We also ought not to talk ourselves into believing the middle powers of the NATO Alliance – that is, all but the United States – are too enfeebled to protect and advance our common interests. Especially at a time when the United States is consumed with domestic debates, relying on the Congress rather than the President to champion the cause of free peoples, NATO’s Canadian and European Allies have the ability and the interest in sustaining the liberal international order, which NATO has been such an important part of creating.

Most NATO statesmen of the past seventy years would gladly trade their problems for ours. The 1950s leaders of the Alliance had to confront a Soviet threat they feared losing a war against in a series of crisis confrontations. The 1970s Allies had to navigate a United States impeaching its President, destroying the Bretton Woods financial arrangements, and losing the Vietnam War while having race riots in its military ranks. The 1980s leaders of Germany, Britain, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Italy had to convince their publics to accept deployment and potential use of nuclear missiles. The 1990s leaders had to manage a declining Russia, the Balkan wars, and demands for inclusion by deserving democratic states newly liberated from Soviet dominion. The 2000s leaders had the problems of terrorism and a disgruntled Russia seeking to destabilize our democracies.

NATO has never been easy. It has just always been a better solution than any of us could find outside the Alliance. As Scott Fitzgerald writes concluding The Great Gatsby, “So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past”. Know, though, at this 70th anniversary of the Alliance, that NATO’s founders would be both surprised and proud to see how well the loose coalition of frightened and like-minded states persevered in the face of danger.

No comments:

Post a Comment