By THERESA HITCHENS

WASHINGTON: The U.S. failure to speak out publicly and more forcefully against India’s anti-satellite (ASAT) tests may backfire, former U.S. government officials and space experts say, clearing a path for continued testing and development of debris-creating weapons that Pentagon leaders have been saying for years are unacceptable.

WASHINGTON: The U.S. failure to speak out publicly and more forcefully against India’s anti-satellite (ASAT) tests may backfire, former U.S. government officials and space experts say, clearing a path for continued testing and development of debris-creating weapons that Pentagon leaders have been saying for years are unacceptable.

The United States has “more reasons than any other country to want to prevent creation of debris. We have the biggest economic and military and commercial interest in space, hands down, by a factor of two or three,” explains Doug Loverro, former deputy assistant secretary of Defense for space policy. “We should be in the forefront of calling for an international convention to outlaw debris-creating weapons, and anybody and everybody in this [space policy] community knows we should be doing more towards that outcome.” So far, he lamented, there has been no one in the United States with any real “gravitas” willing to pick up that baton.

Frank Rose, former State Department assistant secretary for arms control, verification and compliance, agrees. “We need to create a norm against debris creating events in outer space. If ever there is real conflict, those satellites [destroyed] won’t be at 300 kilometers, but at 800 or so kilometers – where there will be significant damage to the space environment.” While praising the Trump administration’s sharp focus on space security overall, Rose criticized the almost startling lack of a diplomatic element to the current strategy. “They quite frankly have not been at the table on the diplomatic front,” he told me in a phone interview today, “despite talking a good game about support for norms.” The India ASAT test, he said, could have provided an opportunity for leadership from the Trump administration.

The bland official State Department response to the Indian ASAT test came in an email statement to The Hindu. It’s a clear reflection of the great strategic importance of India in the Pacific, as a counter to China.

“The issue of space debris is an important concern for the U.S. government. We took note of Indian government statements that the test was designed to address space debris issues,” a State Department spokesperson said. However, the spokesperson added, the United States, as part of its “strong strategic partnership with India,” will continue “to pursue shared interests in space and scientific and technical cooperation, including collaboration on safety and security in space.”

In fact, the State Department held its ninth round of bilateral talks March 13 under the so-called U.S.-India Strategic Dialogue on nuclear issues. The day before that, assistant Secretary of State for arms control and verification Yleem Poblete met with her Indian counterpart Maney Pandi in the third round of the U.S.-India Space Dialogue. According to a joint statement, the space talks covered “trends in space threats, respective national space priorities, and opportunities for cooperation bilaterally and in multilateral fora.” There is no evidence that Poblete took the opportunity to caution Delhi about its ASAT test plans. Rather, there is reason to believe that the Trump administration’s increasingly sharp rhetoric, in both bilateral talks with allies and multilateral fora, about threats to space from Russia and China actually galvanized Indian thinking about the need for an ASAT test to prove its determination to stand up to Beijing.

The lack of an official scolding of India has sparked concern in the expert community that U.S. policy may backfire. Noting that the United States failed to report the fact that it not only knew in advance about the March 27 test, but that it also knew about a failed Indian test in February (first reported by colleague Ankit Panda in the Diplomat), the Secure World Foundation’s technical advisor, Brian Weeden, worried in a long Twitter rant on April 1 that the United States “seems to be just a bystander” as others create norms of behavior in space that are not in its interests. “So much for leadership,” he tweeted.

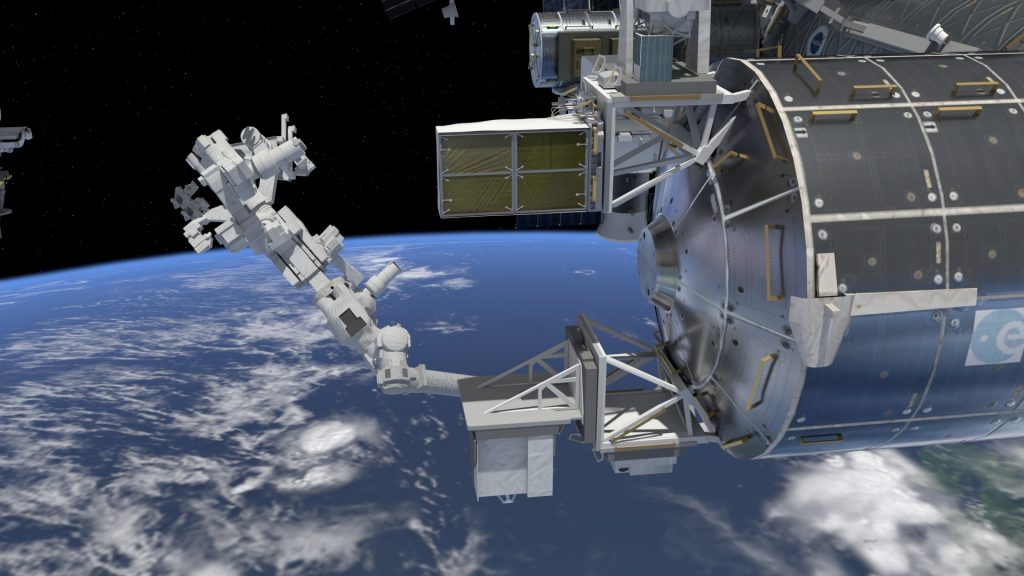

So far, only NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine has gone on the record condemning the test, and it looks like his remarks were — while spot on — a bit off the reservation. As first reported yesterday by Sarah Lewin of Space.com, Bridenstine told a NASA Town Hall meeting on April 1: “That is a terrible, terrible thing, to create an event that sends debris in an apogee that goes above the International Space Station.” He added: “And that kind of activity is not compatible with the future of human spaceflight that we need to see happen.” Bridenstine fretted that all commercial and civil space activities “are placed at risk” by such tests, adding unhappily: “and when one country does it, other countries feel like they have to do it as well.”

Bridenstine, in a speech televised on NASA TV, said the test created at least 60 pieces of debris bigger than 10cm in diameter that are being tracked by the U.S. Space Surveillance Network, 24 of which were thrown into an orbit above the ISS’s approximately 400km orbit. That means those debris pieces have the potential to harm the station as their orbits decay. Bridenstine later sought to reassure the public by saying that currently the ISS and its astronauts are in no immediate danger. Bridenstine put the increase in risk to the ISS at 44 percent due to the new debris, but as one space scientist said: “One fourty-fourth of tiny is still tiny.” NASA’s Orbital Debris Office at Johnson Space Center refused to comment about its risk calculations. Nonetheless, even tiny pieces of space debris can damage or even destroy a spacecraft due to the high speeds of objects on orbit.

The official U.S. catalog of space objects maintained by the 18th Space Control Squadron has yet to publish any official data on where the debris is in orbit. U.S. military officials have said in recent days that between some 250 and 270 debris pieces currently are being tracked by the U.S. Space Surveillance Network of optical and radar sensors. (As an aside, a number of experts said the slow response of the U.S. space situational awareness process highlights the need to shift the mission to a civilian agency and create an internationally based, independent SSA regime.)

Daniel Porras, space security fellow at the United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research (UNIDIR) in Geneva said the muted reactions to the Indian ASAT test are strengthening the argument that “generating debris under, say 300km, is OK” – a viewpoint that began gaining traction in the international community after the vastly different responses to China’s 2007 ASAT test and the U.S. Operation Burnt Frost. The Chinese test took place at about 800km, in a heavily used and highly polluted orbit. The Chinese were sharply criticized by most of the international community. The 2008 Burnt Frost mission, during which the United States destroyed a malfunctioning weather satellite at an orbit of about 250km, did not elicit much response because the debris created mostly cleared out of orbit within about a year. This perception, he and other experts said, is false.

“While not as irresponsible as the 2007 Chinese test, which was right in the range of a lot of expensive stuff on orbit and much of the debris still remains there, India’s test was still irresponsible,” said Jonathan McDowell, an astrophysicist at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. He explained that it is very difficult to predict where debris will end up. Even at very low orbits some debris created by a KE missile impact with a satellite is likely to be boosted to higher apogees. So, he said, it is “not in the interests of the United States to in any way encourage such tests.”

Marco Langbroek, a respected satellite tracker based in the Netherlands, wrote in his SatTracCam Leiden blog that the Indian test’s debris is likely to closely parallel the fallout from Operation Burnt Frost, which resulted in 174 pieces of debris big enough to be tracked by Strategic Command. A significant fraction re-entered the the atmosphere and burned up within two months; almost all did within six months. That said, Langbroek explained, almost 65 percent of the tracked debris from Burnt Frost initially was kicked into orbits higher than the ISS – despite all the efforts the United States had made to minimize the debris footprint. So, as T.S. Kelso, keeper of the Celestrak website for monitoring space objects and a senior astrodynamicist at Analytical Graphic Inc.’s Center for Space Standards and Innovation, told me: “Hitting the target is the easy part. Knowing exactly where you hit and how the object will come apart is obviously more difficult than some may wish to admit. And shredding a 740-kg satellite into 1-kg chunks (for example) would leave quite a mess and even if a couple headed toward the ISS orbit, that could be bad.”

In other words, there is no “safe” way to conduct kinetic energy ASAT tests; and there is no “safe” way to conduct KE ASAT attacks on satellites during wartime. What, if anything, is the United States going to do about it?

No comments:

Post a Comment