J. Stapleton Roy

The U.S. National Security Strategy released in December 2017 identifies China and Russia as key rivals of the United States. The formulation of a strategy to address the challenges they pose requires a clearheaded understanding of the relationship between Moscow and Beijing, which is cemented by common strategic interests but marred by historic mistrust and differing national trajectories. U.S. policies have at times inadvertently driven China and Russia closer together, to the detriment of U.S. interests. Policymakers should neither exaggerate the degree of convergence between Chinese and Russian interests nor ignore the significant factors that underlie their cooperation. Skillful U.S. diplomacy can moderate the adverse impact of Sino-Russian solidarity, identify areas where trilateral cooperation is possible, and through careful management of relations with Moscow and Beijing, influence the future direction and nature of Sino-Russian relations. Similarly, potential congressional actions focused on U.S. relations with Russia and China need to be weighed carefully in the light of these considerations.

The State of Sino-Russian Relations

For over three decades following the breakthrough in U.S.-China relations in the early 1970s, the United States occupied the favored position in the strategic triangle between Washington, Moscow, and Beijing, China now occupies the position of having the best relationships with the other two. The reasons for this shift lie in three developments in Eastern Europe: the fall of the Soviet Union, the persistent eastward expansion of NATO and European Union membership without regard to Russian objections (especially over NATO), and the crisis in Ukraine that erupted in 2014.

The disintegration of the Soviet Union essentially negated the threat from Russia in China’s eyes and vastly reduced the element of their great-power rivalry. Their once-frosty relations became warm and cooperative, albeit with some reservations on the Russian side. Chinese and Russian public attitudes toward the other country were positive. Each side was deferential on issues of primary importance to the other: for China, North Korea was paramount; for Russia, Ukraine and Syria.

The countries have good reasons to foster strategic cooperation. They both are opposed to a world dominated by a sole superpower. They both feel threatened by the propensity of the United States for unilateralism, interventionism, and support for color revolutions. Their economies are complementary, with Russia supplying military equipment, energy, and raw materials, while China provides capital and consumer goods. They have a common interest in not allowing Central Asia to become a breeding ground for terrorism. China has been sympathetic to Russian concerns about NATO’s eastern expansion, which mirrored Beijing’s own worries that the United States was pursuing a policy of encircling and containing China.

A turning point in Sino-Russian relations occurred in 2014, when Moscow confronted the West over the issue of Ukraine’s potential membership in the European Union and NATO by annexing Crimea and supporting rebel movements in eastern Ukraine. Under the impact of Western sanctions, Russia set aside the reservations that had limited its cooperation with China in areas such as energy, regional infrastructure development, security in Central and South Asia, and the sale of advanced weaponry. These developments rang alarm bells in Washington.

Indicative of this shift, after the 2014 Ukraine crisis, Russia agreed to sell China the S-400 air and missile defense system, which it had earlier been reluctant to provide; endorsed Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative; and concluded energy deals with Beijing that had long been held in abeyance. The two sides also held joint military exercises in Northeast Asia and the South China Sea. Russian leaders are grateful for China’s willingness to stand by them in the face of NATO pressure, but they are less comfortable than their Chinese counterparts at moving into this closer embrace.

A Stable but Imbalanced Strategic Partnership

Until now, neither Russia nor China has believed that its interests would be served by forming a strategic alliance against the United States. A large part of this calculation is economic. Although Sino-Russian trade increased twenty-fold over the past 25 years, reaching a height of approximately $95 billion in 2014, China’s trade with the United States was six times as large that year and ten times as large in 2015. [1] Chinese investment is pouring into Russia and the states of the former Soviet Union, and China is now Russia’s largest trading partner. Yet there is still minimal Russian investment in China, in contrast with the hundreds of billions of dollars of Western investment.

In general, Chinese leaders view the Sino-Russian relationship as a “complex, sturdy, and deeply rooted” strategic partnership rather than a “marriage of convenience.” [2] At the same time, China’s continuing rise is a source of discomfort for many in Moscow, who worry about the strategic implications of a Chinese superpower and resent the junior partnership role they have found themselves in with Beijing. Polls have shown that Russians are concerned about Chinese migration into the border areas in the Russian Far East (which could pose a longer-term threat to Russia’s territorial integrity in eastern Siberia) and believe that a stronger China would harm Russia’s interests. In addition, Russian leaders are worried about China’s competition for influence in the former states of the Soviet Union. Moscow initially was reluctant to support Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative before ultimately embracing it in 2014 after the crisis with the West over Ukraine.

The Impact of Sino-Russian Relations on U.S. Interests

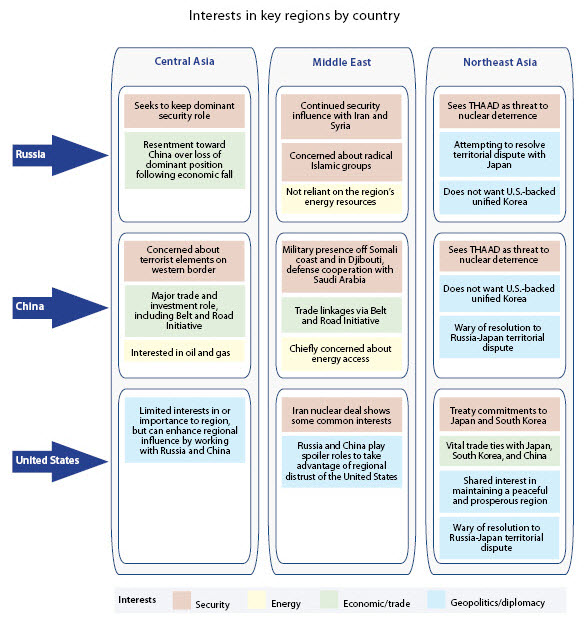

These trends in Sino-Russian relations are particularly relevant to U.S. interests in three regions: Central Asia, the Middle East, and Northeast Asia. U.S. policy and the dynamics of the strategic triangle in these regions will be key factors in determining the degree and nature of the impact of closer cooperation between China and Russia on U.S. interests (See a summary chart below).

Central Asia. China and Russia are both collaborators and sparring partners in Central Asia. Closed to Chinese influence during the prolonged period when it was part of the Russian empire and the Soviet Union, Central Asia has now resumed its traditional role as a cockpit for major-power competition and as a crossroads for interactions between Europe, the Middle East, South Asia, and East Asia. Russia nurses deeply felt grievances over the loss of its dominant position in Central Asia. China in turn is moving quickly to fill the vacuum left by an economically weakened Russia through economic penetration and ambitious infrastructure projects, including the Belt and Road Initiative. This has made Central Asia a testing ground for the balance between cooperation and rivalry in Sino-Russian relations.

Not surprisingly, Russia still has a proprietary interest in its former territories in Central Asia and wants to retain its dominant role, especially in the security sphere. China, for its part, already plays a significant trade and investment role in Central Asia and is keenly interested in the region’s oil and gas resources. It has generally respected Russia’s security concerns and has kept its focus on trade and energy. However, in addition to China’s economic interests in Central Asia, Xi’s proposal in May 2014 for the establishment of a new security and cooperation mechanism in Asia demonstrated that Beijing also views the region from a security perspective that is broader than its desire to block terrorist elements from infiltrating Xinjiang. [3] Implementation of the Belt and Road Initiative would advance Beijing’s declared intention to become a major global power.

The United States needs to be engaged in Central Asia in order to be well informed on developments, but it should not exaggerate its importance. The interests of both Russia and China in the region are greater and more sustainable. Central Asian countries welcome the U.S. presence as a balancing factor but are conscious that Russia and China have long-standing geographic interests, while the United States’ role is more ephemeral. Washington will be more effective in enhancing its regional influence if it can work cooperatively with both Moscow and Beijing.

The Middle East. Unlike in Central Asia, Russian and Chinese interests in the Middle East differ significantly. As an oil and gas exporter, Russia is not dependent on the region’s rich energy resources. Since the Soviet Union’s collapse, Moscow has been concerned with countering the threat of terrorism fomented by radical Islamic groups, along with preserving its influence with countries such as Iran, where Russia has had traditional interests, and Syria, a former and present client state.

For China, by contrast, access to Middle Eastern energy resources is an important national interest. Its presence in the region has been centered on expanding economic and trade links, now enhanced by the Belt and Road Initiative. The country’s military presence is also growing through its participation in antipiracy patrols off the Somali coast (conducted with a UN mandate) and the establishment of its first overseas military base in Djibouti. Defense cooperation with Saudi Arabia, in particular, is on the rise, partly facilitated by tensions in U.S.-Saudi relations.

Washington will likely find Moscow and Beijing acting more as spoilers than as supporters of U.S. initiatives in the Middle East, given that both have capitalized on U.S. failures. Russia’s military intervention in the Syrian civil war and China’s success in promoting its image as a country that supports state sovereignty and noninterference in domestic affairs illustrate but two of the challenges that Russia and China, working individually or together, pose to U.S. interests. At the same time, the Iran nuclear agreement illustrates that in limited areas Washington can find common interests with both Moscow and Beijing in the Middle East.

Northeast Asia. Russian and Chinese interests in Northeast Asia contain substantial areas of alignment but are not identical. Both countries strongly oppose North Korea’s nuclear weapons program, if only because of the proliferation pressures this puts on Japan and South Korea. At the same time, because both countries dread the prospect of a unified Korean Peninsula within a Western alliance system, neither favors instability or the collapse of the Kim Jong-un regime or a strengthened U.S. military posture on the peninsula.

At the same time, China shares a much longer border with North Korea than does Russia and has a substantial ethnic Korean population in adjacent areas. China also incurred massive casualties in the Korean War, while the Soviet Union did not. For these reasons, Moscow seeks participation in matters affecting the Korean Peninsula but often defers to Beijing on substantive issues.

Both Russia and China have opposed the U.S. deployment of the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) anti-ballistic missile systems in South Korea. While THAAD is meant to counter the North Korean missile threat, Beijing and Moscow are both concerned that the powerful radars associated with THAAD will strengthen the U.S. ability to monitor their own missile development and adversely affect nuclear deterrence.

China and the United States, each for their own reasons, likely harbor reservations about whether a resolution to island disputes between Russia and Japan is desirable. Beijing and Washington would need to tread carefully in expressing their views because of the damage this could do to important relationships—with Moscow in the case of Beijing, and with Tokyo in the case of Washington.

This said, all the major powers in Northeast Asia have a common interest in seeing the region remain peaceful, prosperous, and stable. The key question is whether their respective policies toward one another will serve this purpose.

U.S. Foreign Policy Considerations

We are well along in the process of moving from the post–Cold War world we have known for the last 25-plus years to a new world without a single hegemonic superpower. The rapid rise of developing countries such as China, India, and Brazil is creating a multipolar world with a number of powerful actors and a larger group of lesser but strong secondary players.

Asian leaders recognize that, despite China’s rapid military modernization, the United States still has a substantial edge over China in terms of air and naval power. Nevertheless, some countries in East Asia are beginning to adjust their foreign and security policies to accommodate Chinese interests, just as countries farther west are adjusting to Russian interests. If the United States wants to play a leading role in fashioning the new balance of power, in which China and Russia are both key elements, it must move quickly to address the erosion of confidence in the ability of the United States to maintain its traditional role as the guarantor of regional peace and stability.

Policy Implications

Cooperation between Russia and China is a current reality and is likely to continue. Congressional committees, including House Foreign Affairs and Senate Foreign Relations, should stay abreast of developments in this relationship, given that Sino-Russian cooperation has the potential to threaten vital American interests.

U.S. foreign policy must realistically adjust to the shifting global power balance and adopt an approach that is consistent with fundamental U.S. interests and principles. Congress should use its budgetary power to ensure that these policies are sustainable and affordable.

U.S. management of relations with Moscow and Beijing can be an important factor in determining the future direction and nature of Sino-Russian relations. Easing tensions between the West and Russia in Europe, such as by formally revoking the statement in the Bucharest Summit Declaration of April 3, 2008, that Georgia and Ukraine “will be members of NATO,” could help restore a more normal pattern of limited cooperation between Russia and China.

In regions where China and Russia have stronger historic and geographic interests than the United States, as in Central Asia, or where their alignment can adversely affect U.S. interests, as in the Middle East, the United States should not try to play a spoiler role but should engage with both countries when desirable and resist their individual and collective challenges to U.S. interests when necessary.

Congressional approval of defense sales to partners in the region is critical for the United States to continue its role as the guarantor of regional peace and stability, as is the continuation of congressional delegation exchanges with the legislatures of U.S. friends and allies.

NOTE: This brief is made possible by a grant from the Henry M. Jackson Foundation and draws on the author’s contribution to the NBR Special Report “Russia-China Relations: Assessing Common Ground and Strategic Fault Lines” (July 2017).

No comments:

Post a Comment