Davide Cancarini*

The Asia Pacific region is one of the areas with the highest growth potential for the coming decades. This potential is contingent on the need to ensure adequate infrastructure, no easy task given recent estimates by the Asian Development Bank, with spending needs for infrastructure in the Asia Pacific region predicted to top 1.7 trillion dollars a year.[1]

The Asia Pacific region is one of the areas with the highest growth potential for the coming decades. This potential is contingent on the need to ensure adequate infrastructure, no easy task given recent estimates by the Asian Development Bank, with spending needs for infrastructure in the Asia Pacific region predicted to top 1.7 trillion dollars a year.[1]

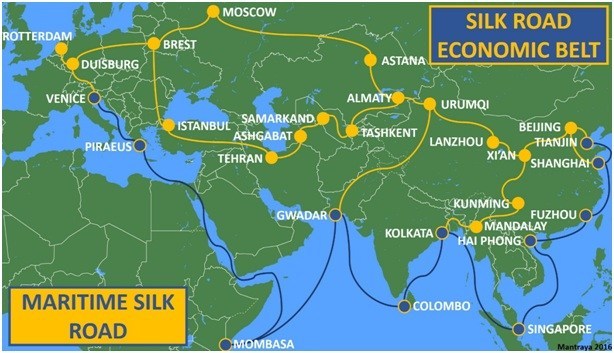

When it comes to massive infrastructure investments, China’s signature Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), officially launched by President Xi Jinping while on a state visit to Kazakhstan in 2013, has attracted most international interest and attention.

Figure 1 | The Belt and Road Initiative

Source: Boh Ze Kai, “One Belt, One Road, One Singapore – Analysis”, in Eurasia Review, 13 April 2016, http://www.eurasiareview.com/13042016-one-belt-one-road-one-singapore-analysis.

Given its geographical location as a privileged corridor on the east-west axis, Central Asia lies at the very heart of the BRI’s land trade links. China, however, is not the only regional player with the potential to give a decisive boost to Central Asian connectivity.

The other Asian giant, India, has also begun to move in this direction. In so doing, India has attracted the interest of several regional players, motivated by an effort to find other external partners capable of balancing China’s growing involvement in their neighbourhood.

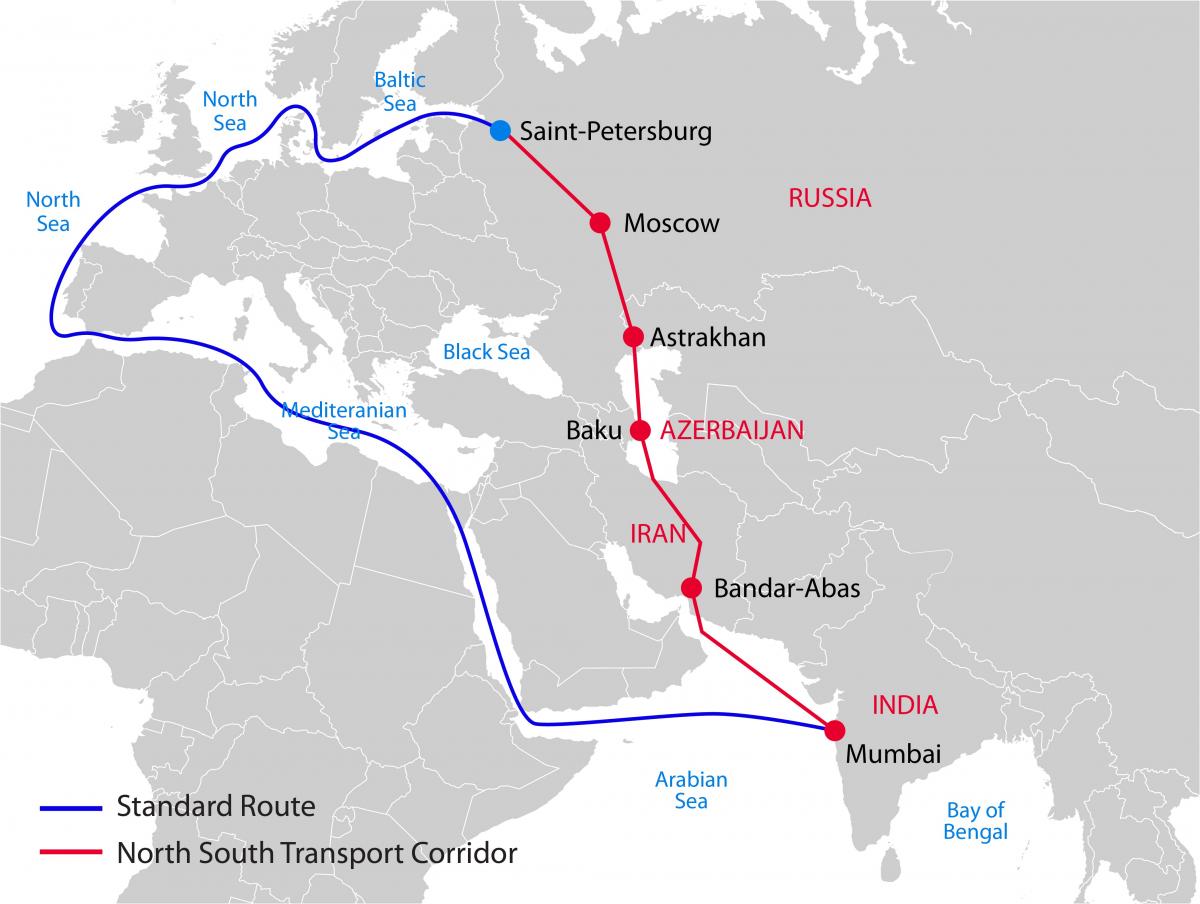

India’s strategy is articulated within the framework of New Delhi’s key infrastructure project, the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC). The objective is to guarantee a faster route between Indian and Russian territory, allowing Indian goods (such as clothing, chemicals and agricultural products) to reach Iran, Central Asia and some parts of Europe while bypassing Pakistan, India’s historic rival. Increasing Indian imports of Central Asian and Iranian natural gas, oil and uranium is also a key goal in this regard.

A completed INSTC could boost trade exchanges between India and Central Asia (including Iran), with estimatespredicting an increase to 170 billion dollars, from the current 1 billion level.[2] By way of comparison, in 2016, trade between China and Central Asia amounted to 30 billion euro.

Figure 2 | Map of North South Transport Corridor route via India, Iran, Azerbaijan and Russia

Source: Boris Volkhonsky, “North-South Transport Corridor Begins Functioning”, in Russia Beyond, 12 December 2016, https://www.rbth.com/blogs/the_outsiders_insight/2016/12/12/long-awaited-north-south-corridor-close-to-launch_655489.

The clearest representation of the ongoing infrastructure competition between China and India are the ports of Gwadar in Pakistan (backed by China) and the Iranian port of Chabahar (backed by India). Located near the Gulf of Oman and about 150 km from each other, they represent two different and competing trade access points.

Gwadar port has been developed by China within the framework of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) – a branch of the BRI that includes a series of initiatives to modernise Pakistan’s infrastructure – and represents Beijing’s door to the Indian Ocean. On the other hand, Chabahar is New Delhi’s entrance gate to Iran and Central Asia, especially when a planned railway on Iranian territory to the border with Afghanistan is completed.[3]

Figure 3 | NSTC vs CPEC

Source: Apurva Agraval, “Chabahar Port – India’s Gateway to Central Asia”, in Steel 360 News, 2 January 2017, https://news.steel-360.com/?p=5752.

From a commercial point of view, the two projects have different objectives: Gwadar aims to allow China to increase its access to the Indian Ocean; Chabahar will allow Indian imports and exports to and from Central Asian markets and provide an opening for New Delhi to take part in the Afghan reconstruction.

Looking at the strategic implications of the Central Asian sections of the BRI and the INSTC, will clarify Indian and Chinese concerns. India fears that once trade links are strengthened, China could influence the foreign policy choices of regional states. Gwadar is also viewed by India as a potential Chinese naval outpost in the Indian Ocean, raising further concern. Finally, the CPEC may destabilise the disputed region of Kashmir since some parts of the planned route pass through the territory of Gilgit Baltistan.

Between the two, the Gwadar project – which according to Chinese authorities will be fully operational by 2020/2021[4] – and the broader CPEC are certainly more controversial. Despite the potential economic benefits, the project is generally seen as a top-down initiative lacking attention for local dynamics and has met the opposition of the populations involved.[5]

In the Asian infrastructure game, some players act on the basis of clear objectives. Other transit countries, however, are playing a more ambiguous game.

Iran has acted like a pendulum, supporting Chinese or Indian objectives depending on the circumstances while forging links with both.

China and India are Iran’s top oil importers.[6] While, Iran has strongly backed the India-supported Chabahar port project, this has not prevented Tehran from signing an agreement with China to build a railway between the cities of Shiraz and Bushehr last March.[7] Clearly, Tehran is trying to balance its relations with the two Asian giants, seeking to maximise returns at a time of increased international pressure.

Much of the same can be said for Uzbekistan. The “double-landlocked” nature of the country, has forced Uzbek authorities to try to increase land and air connections to the outside. China is Uzbekistan’s largest trade partner and Beijing is supporting Uzbek authorities in improving their infrastructure. In late 2017, for example, a China-backed railway between the Uzbek capital and the Chinese city of Kashgar was inaugurated.[8]

Uzbekistan has been one of the regional players most interested in exploiting India’s infrastructure dynamism which, with reference to Central Asia, finds its origin in the 2012 “Connect Central Asia Policy”, a new approach to the region that aims to strengthen political, economic, security, logistical and cultural relations.

It is no coincidence that Uzbek leader, Shavkat Mirziyoyev, asked New Delhi to participate in a project to build a 650 km railway between Mazar-i Sharif and Herat in Afghanistan during his latest official visit to India last September.[9]This would be the continuation of a railway built in 2011 that connects Hairatan – on the Uzbek-Afghan border – to Mazar-i Sharif.[10] Once another project, a railroad between Herat and the Iranian city of Khaf is completed (according to Iranian authorities, by 2019), Uzbekistan would potentially be connected by land, through Afghanistan and Iran, with the Persian Gulf. In this regard, the Afghan rail project would provide Uzbekistan a direct and privileged link to the Iranian port of Chabahar, thereby also boosting Indian interests.

While controversial due to the opposition of local communities in transit countries, the Gwadar project seems to have more chances of success, mostly due to broader geopolitical dynamics.

This is linked, firstly, to India’s capability to attract the interest of other countries in using its infrastructure projects connected to Iran’s Chabahar port. Such efforts will not be easy given growing US and Arab Gulf states pressure on Iran following the re-imposition of US sanctions on Tehran. Moreover, the present limits of infrastructure development in Central Asia and the obstacles posed by the security situation in Afghanistan, also pose challenges.

Conversely, Gwadar port and its related infrastructure links are not burdened by similar pressures, excluding opposition coming from part of the population of Balochistan. In fact, the project relies on more solid commercial foundations and massive Chinese investments.[11] Furthermore, while India’s INSTC project may rise concern in the US due to the pivotal role granted to Iran, China is not bothering Russia with its action in Central Asia, historically Moscow’s backyard.[12]

Beijing, therefore, seems better positioned than India in both the “ports challenge” and the more general infrastructure competition in Central Asia. Against this backdrop, and while a continuation of this competition is likely to persist, it is not unthinkable for Beijing and New Delhi to move towards cooperation. For example, China would like to include India’s Kolkata in its Maritime Silk Road, an eventuality still being debated.

The most important step towards infrastructure cooperation would be Beijing’s participation in the development of the port of Chabahar. Iran has repeatedly welcomed this possibility. This could happen if India realises that it has to come to terms with Beijing to make its project commercially viable. For China, this would mean limited additional investments, compared to the tens of billions of dollars already invested in the BRI, with a significant return in strategic terms.

While it is too early to tell weather this eventuality will materialise, what is certain today is that, in the short term, regional players, including Iran, Uzbekistan and Afghanistan, seem to be the main beneficiaries of this ongoing infrastructure competition between China and India in Central Asia.

* Davide Cancarini, PhD in Institutions and Policies from the Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore in Milan, has worked extensively on Central Asian affairs.

No comments:

Post a Comment