by Nadège Rolland

This backgrounder from NBR Senior Fellow Nadège Rolland, author of the book China’s Eurasian Century? Political and Strategic Implications of the Belt and Road Initiative, provides an overview of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) ahead of the second Belt and Road Forum on April 25–27. Read the backgrounder below.

ORIGINS

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) was set in motion by Xi Jinping in two speeches. During his address to the Nazarbayev University in Kazakhstan in September 2013, Xi proposed the idea of a Silk Road Economic Belt, connecting China to Europe via land, in order to “forge closer ties, deepen cooperation and expand the development space in the Eurasian region.” One month later, as he was addressing the Indonesian parliament in Jakarta, Xi proposed the creation of a 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, connecting China to Europe via sea, that would increase connectivity and maritime cooperation with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).

The Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road became “One Belt, One Road” for short. In late 2015, the central government issued guidelines on standardizing the English translation, specifically demanding that “initiative” should now be used in association with Belt and Road, whereas “strategy,” “project,” “program,” and “agenda” should not be used. One Belt, One Road became Belt and Road Initiative in English, but its Chinese name remained “Yidai Yilu.”

NARRATIVE

The historical reference to the ancient Silk Road, now buried within the BRI abbreviation, is still unmistakable. The term “Silk Road” was coined by German geographer Ferdinand von Richtofen in 1877. In China, the ancient trading routes across Eurasia were more prosaically called the northern and southern routes.

The reference to the ancient Silk Road was not chosen by chance. It conjures up images of peaceful and diverse exchanges from one prosperous end of the Eurasian continent to the other and is easily identifiable in countries outside China as a shared heritage defying civilizational differences. Chinese sources never refer to BRI as the “New Silk Road.” This term is the name of a U.S. initiative envisioned in 2011 as a means to further integrate Afghanistan with its neighbors via the reconstruction of infrastructure links broken by decades of conflict.

Beyond historical references, the official narrative attached to the public representations of BRI is mainly framed around “peace and development,” a favorite theme of the Chinese leadership since 2003. BRI’s objectives are officially to “promote the economic prosperity of the countries along the Belt and Road, promote regional economic cooperation, strengthen exchanges and mutual learning between civilizations, and promote world peace and development.”

CENTRAL AND CENTRALIZED

BRI is highly centralized and coordinated from the top of the Chinese political leadership. The initiative was enshrined in the Chinese Communist Party’s constitution during the 19th Party Congress in October 2017, and its corollary, “the community with a shared future for humanity,” was included in an amendment to the People’s Republic of China constitution in March 2018.

Two central ad hoc task forces were created in March 2015 under the State Council’s purview in order to supervise all BRI-related activities: the Leading Small Group on Advancing the Construction of the Belt and Road and its subsidiary, the Office of the Leading Small Group on Advancing the Construction of the Belt and Road, located within the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), which manages the day-to-day central oversight and coordination work with relevant ministries and entities. The Belt and Road Promotion Center was established in 2017 within the NDRC’s office. It fulfils a strategic planning mission, which includes, among other tasks, the “analysis and assessment of relevant countries’ political and economic situations.”

Following the 13th National People’s Congress in March 2018, Vice Premier and Politburo Standing Committee member Han Zheng became chairman of the leading small group, while State Counselor and former minister of foreign affairs Yang Jiechi, Vice Premier Hu Chunhua, Secretary General of the State Council Xiao Jie, and NDRC Director He Lifeng assumed the responsibility of vice chairmen.

BRI leading small groups have also been created in relevant Chinese ministries and in each Chinese province. Similar to the central one, ministerial and provincial groups meet on a regular basis and include representatives from a variety of relevant government entities whose responsibilities pertain to the advancement of BRI.

At the top of the chain, Xi Jinping himself gives guidelines during regular study sessions specifically dedicated to BRI (such as the Politburo sessions on December 5, 2014, April 29, 2016, and September 27, 2016) or uses important events such as the Central Committee 5th Plenary Session (October 29, 2016) or the 19th Party Congress (October 18, 2017) to deliver important messages regarding the initiative. A compilation of 42 BRI-related speeches and public addresses by Xi was published by the Central Party Literature Press in December 2018.

On August 27, 2018, Xi chaired a symposium to mark the fifth anniversary of the launch of BRI. The symposium gathered all the domestic elements essential to the smooth implementation of his instructions: leaders of provinces, districts, and municipalities; representatives from businesses; experts and scholars; and officials from the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection and the Supreme Court.

According to Chinese official sources from the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission, since 2013, 80 Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) have undertaken over 3,100 BRI projects.

“Hard” infrastructure projects occur mostly in the following sectors: transportation (ports, roads, railways), energy (pipelines, power grids, hydropower dams), and information technologies and communications (fiber-optic networks, data centers, satellite constellations). In addition, “soft” infrastructure projects are also underway, such as the creation of special economic zones and the negotiation of free trade agreements, currency swap agreements, and reduced tariffs.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT

According to estimates by the Asian Development Bank (ADB), there is a funding gap of $26 trillion ($1.7 trillion annually) for the infrastructure projects that will be required in Asia by 2030. The most common estimates for the current proposed total budget for BRI are $1 trillion and $1.3 trillion. However, neither Xi Jinping nor any other member of the Chinese top leadership has ever announced an overall budget figure attached to BRI.

The rough $1 trillion estimate found in open sources is generated by totaling various announcements over the years:

In November 2014, Xi announced the creation of the Silk Road Fund, endowed with $40 billion from China’s foreign exchange reserves and policy banks.

In June 2015, the China Development Bank announced that it would invest $890 billion in 900 BRI projects.

In January 2016, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) began operations with $100 billion in capital. The AIIB mostly co-funds projects with other multinational development finance institutions such as the World Bank and the ADB.

In May 2017, several additional announcements were made during the Belt and Road Forum:

Ning Jizhe, the vice chairman of the NDRC, claimed that China’s investments would total between $600 and $800 billion ($120 to $160 billion a year) over the next five years.

Xi Jinping pledged an extra $14.5 billion for the Silk Road Fund, as well as $56 billion in loans from two policy banks and $9 billion in aid to developing countries and international bodies in countries along the new trade routes.

In January 2018, the China Development Bank committed $250 billion in loans to BRI.

BRI investments have also been estimated at as high as $8 trillion, a figure that seems to emanate from a 2009 ADB report projecting that Asia needed to invest approximately this amount in national infrastructure between 2010 and 2020.

GEOGRAPHIC SCOPE

There exists no official map showing all the projects undertaken under the BRI banner or all the places considered as “Belt and Road countries.” A map published by China’s state-owned Xinhua news agency in May 2014 provides the closest approximation to what the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road looked like at their inception. But the thin continental and maritime lines look more notional than concrete.

BRI’s geographic scope is constantly expanding. In the early years after the initiative’s launch, Chinese sources regularly mentioned that between 60 and 65 countries were included in BRI. Since then, the number has grown to 70 (at the time of the May 2017 Belt and Road Forum) and most recently to 123, according to statements by Ning Jizhe on the sidelines of the annual meetings of the national legislature and the top political advisory body in March 2019. Ning also claimed that 29 international organizations are working within the BRI framework.

Formerly centered on the broader Eurasian continent, BRI has since 2017 expanded to include the African continent, portions of Latin America, Oceania, and the Arctic Ocean. In addition to geographic regions, it also includes a digital Silk Road and a Silk Road in outer space. The initiative is thus pushing China’s outlook well beyond its traditional periphery.

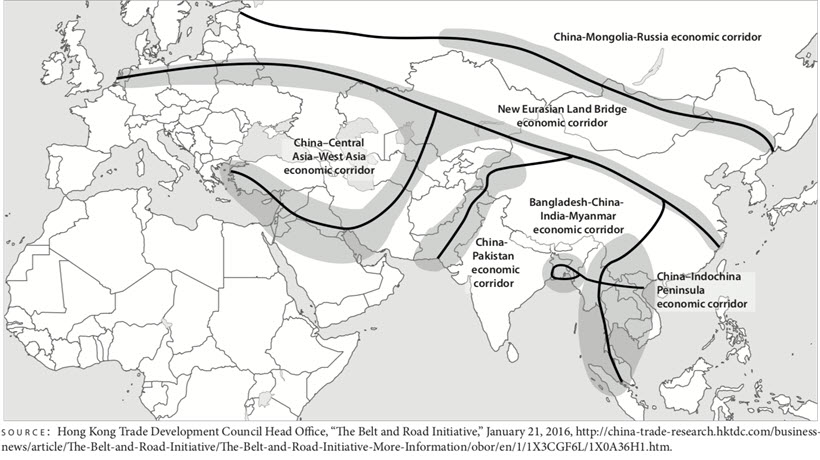

BRI comprises six “economic corridors” that create spoke-like linkages between China, positioned as the center of a hub, and several of its neighboring regions:

China-Mongolia-Russia Economic Corridor

New Eurasian Land Bridge Economic Corridor

China–Central Asia–West Asia Economic Corridor

China-Pakistan Economic Corridor

Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar Economic Corridor

China–Indochina Peninsula Economic Corridor

In addition, three “blue economic passages” have been outlined in a document published in June 2017 by the NDRC and the State Oceanic Administration:

China–India Ocean–Africa–Mediterranean Sea Blue Economic Passage

China–Oceania–South Pacific Blue Economic Passage

China–Arctic Ocean–Europe Blue Economic Passage

BEYOND INFRASTRUCTURE

The focus generally given to the infrastructure-building activities undertaken under BRI masks the fact that the initiative comprises “five connectivities” or “five links”: policy coordination, infrastructure building, unimpeded trade, financial integration, and people-to-people exchanges. Taken together, these five links reflect the Chinese leadership’s vision for a region more deeply integrated around China, forming a Sinocentric order. The ultimate objective of BRI is not only to enhance infrastructure connectivity across Eurasia but to “move toward a community of common destiny and embrace a new future.”

The “community of common destiny,” which is sometimes translated as the “community of shared future for humankind,” has emerged as one of Xi Jinping’s favorite phrases. It is far from a bland and well-meaning platitude. Although the phrase has appeared more than a hundred times in Xi’s public speeches since 2013, there is no official definition of what it entails. There is nevertheless an emerging common understanding among Chinese intellectuals that the community reflects a dissatisfaction with the current U.S.-led international order and aspires to offer a “better way” than the Western one for organizing the world and to “improve the global governance.”

DRIVERS AND MOTIVES

BRI has become so ubiquitous in China’s external discourse and practice that it is now almost impossible to distinguish it from Beijing’s foreign policy. But it is also designed for domestic purposes.

BRI has been designed to serve what Xi Jinping characterized in 2012 as the “China dream of the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation”: the accomplishment of China’s unimpeded rise. In his address to the 19th Party Congress, Xi noted that “the Chinese nation…has achieved a tremendous transformation—it has stood up, grown rich, and become strong.” For this objective to be achieved, the Chinese leadership strives to transform China into an economically, diplomatically, politically, socially, culturally, and militarily strong country (qiangguo): “Such a holistic approach calls for a focus on both internal and external security. Internally, it is essential to promote development, continue reform, maintain stability, and create a safe environment. Externally, we should promote international peace, seek cooperation and mutual benefit, and strive to bring harmony to the world.”

In line with this holistic approach, BRI’s drivers are both internal and external, both economic and strategic:

BRI is supposed to help sustain China’s economic growth.

BRI has been integrated into the 13th Five-Year Plan, which gives priority to implementing the initiative in order to develop China’s inland provinces.

BRI dovetails with the Made in China 2025 plan (launched in May 2015), which aims to upgrade ten high-tech industries, five of which are directly related to BRI’s development (aviation and aerospace, electrical power, next-generation information technologies, rail transportation, and marine technology).

BRI also dovetails with China’s “internet plus” strategy launched in March 2015 with the intent of fostering a strong high-tech digital sector. A document issued in March 2017 on China’s “International Strategy of Cooperation on Cyberspace” officially calls on domestic internet companies to “take the lead in going global” and specifically mentions BRI when encouraging Chinese IT companies to “actively engage in capacity building of other countries and help developing countries with several e-sectors to contribute to their social development.”

BRI supports the Chinese state conglomerates’ “going global” strategy. Funded by Chinese policy banks (the Export-Import Bank of China and the China Development Bank) and staffed by Chinese workers, regional infrastructure projects would predominantly become the preserve of China’s SOEs, opening new markets for them and helping them build and scale a truly global footprint.

BRI aspires to increase regional e-commerce and cross-border transactions conducted in renminbi, thus accelerating the currency’s internationalization.

BRI aims to reduce the economic development gap between China’s coastal and landlocked inner provinces. Development and enhanced living standards are seen by Beijing as key factors to reduce the risk of social unrest and political instability. They are also seen as the best ways to discourage religious radicalization, fundamentalism, and terrorist recruitment—both within China’s borders and beyond.

BRI is supposed to help strengthen China’s energy security. Uneasy at the thought that its energy imports transit through sea lanes of communication that are under the protection and surveillance of the U.S. Navy, Beijing has for some time been looking for alternative routes to circumvent the so-called Malacca Strait dilemma and diversify its supplies through land routes. The projected and current BRI projects illustrate an attempt to redraw the map of China’s energy supply routes from Iran, the Gulf countries, and eastern Africa, while increasing its imports from Russia and Central Asia. Traveling by sea and land pipelines through Pakistan and Myanmar, or directly by land across Eurasia, some of China’s energy imports would thus bypass the South China Sea, reducing the country’s vulnerability to a potential U.S. naval blockade in case of a military conflict.

Beijing expects that BRI will help “expand its circle of friends” and enhance its broader influence. Instead of gunboat diplomacy and coercive military power, China intends to use BRI to access new markets, increase Chinese control of critical infrastructure assets, and influence regional countries’ strategic decisions. China will use economic leverage both as an incentive to garner support for its interests and reduce potential resistance and as a means to punish recalcitrant countries.

BRI is a counter-encirclement strategy. Chinese strategic planners see the United States as an oppressive global hegemon determined to prevent China’s rise. The U.S. forward military presence and enduring alliance system, together with the United States’ command of the global oceans, have long been seen as posing the most direct and serious challenge to China’s security. When the Obama administration declared its intention to rebalance to the Asia-Pacific in 2011, Chinese strategists concluded that a more intense phase of competition was beginning, and they needed a way to respond. The solution was to avoid direct confrontation on China’s maritime front by consolidating its position westward on the Eurasian continent. This idea was not new. For some years, several Chinese strategists had argued that in response to increased U.S. presence in East Asia, China should seek to preserve a favorable balance of power by enhancing its position on continental Eurasia.

CHINA’S AMBITIONS

BRI advances the Chinese leadership’s ambitions to elevate China as an unchallenged risen power. It reflects a now openly assumed willingness to be proactive internationally, in contrast with Deng Xiaoping’s previous admonition to “hide and bide.” In opening a “new era” for the Chinese nation, which “has stood up, grown rich and become strong,” Xi Jinping set a series of national goals that include becoming “a global leader in terms of composite national strength and international influence,” moving “closer to center stage and making greater contributions to mankind,” and “blazing a new trail for other developing countries to achieve modernization” and providing a “new option for other countries and nations who want to speed up their development while preserving their independence.”

As China’s material power grows, as its economic and political interests expand globally, and as its political influence spreads—all of which will be accelerated by the development of BRI—China is also setting the course to shape the regional and international order in a way that benefits its own interests and favors the Chinese leadership’s worldview. As a top Chinese diplomat wrote in 2016, “the Western-centered world order dominated by the U.S. has made great contributions to human progress and economic growth. But those contributions lie in the past.” The U.S.-led world order is “a suit that no longer fits.”

PUSHBACK

U.S. suspicion about BRI’s intentions started to publicly emerge in 2017. Secretary of Defense James Mattis commented on BRI during a hearing before the Senate Armed Services Committee: “There are many belts and many roads, and no one nation should put itself into a position of dictating ‘One Belt, One Road.’ ”

During a press conference in August 2018, Malaysia’s prime minister Mahathir bin Mohamad commented that “free trade should also be fair trade,” adding that there should not be a situation in which “there is a new version of colonialism happening because poor countries are unable to compete with rich countries.” Mahathir’s comments were then interpreted as leading the charge against China amid rising concerns about BRI’s practices. In an interview with the BBC a few months later, however, he said this was an inaccurate portrayal of his comments.

As BRI began to make progress in various countries and a series of controversial projects came to light, international criticism became more focused on China’s dubious practices and the initiative’s negative impact on local countries. In early 2017, Brahma Chellaney, a professor of strategic studies at the Centre for Policy Research in New Delhi, described BRI as a way for the Chinese leadership to ensnare strategically located developing countries “in a debt trap that leaves them vulnerable to China’s influence.” Echoing the same criticism, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson in October 2017 described China’s model of financing infrastructure projects as “predatory economics” resulting in “financing default and conversion of debt into equity.”

In March 2018, a report from the Center for Global Development warned that 23 of the 68 Belt and Road countries were “significantly or highly vulnerable to debt distress,” of which eight—Djibouti, Kyrgyzstan, Laos, Maldives, Mongolia, Montenegro, Pakistan, and Tajikistan—were particularly at risk. The authors underlined their concern that debt problems “will create an unfavorable degree of dependency on China as a creditor.”

In September 2018, the head of the Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC), a U.S. government international finance development agency, accused China of purposefully plunging recipient countries into debt in order to “grab their assets” and to go after “their rare earths and minerals and things like that as collateral for their loans.”

At the November 2018 Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) summit, without specifically mentioning China by name, Vice President Mike Pence encouraged regional countries to choose the “better option” of U.S. financing: “We don’t drown our partners in a sea of debt. We don’t coerce or compromise your independence. We do not offer a constricting belt or a one-way road.”

In May 2017, the European Union’s 28 member states declined to sign a statement prepared by Beijing to mark the end of the Belt and Road Forum because of a lack of guarantees regarding transparency, sustainability, and tendering processes. A year later, a report co-signed by 27 out of 28 EU ambassadors in Beijing (with the exception of Hungary) condemned BRI for hampering free trade, giving an unfair advantage to Chinese companies, and attempting to shape globalization to suit China’s own interests.

Concomitantly, an increasing number of recipient countries expressed a willingness to return to the negotiating table or even to cancel some BRI contracts because of the financial burden they would impose. For example, Indonesia and Thailand halted high-speed rail projects with China in 2015 (though both countries ultimately went forward after Beijing adjusted its financial terms), Nepal canceled two hydroelectric dam projects, Pakistan put a stop to the $14 billion Diamer-Bhasha dam project due to “unacceptable” funding conditions, and the government of Sierra Leone canceled the China-funded Mamamah International Airport project. In May 2018, Malaysia announced its intention to renegotiate its contracts with China, describing them as “unequal treaties.” Maldives and Myanmar also began to reconsider the scale and scope of their infrastructure cooperation with China.

COUNTER-RESPONSES

Several alternative infrastructure development funding options have started to emerge. The United States increased OPIC’s portfolio cap from $30 billion to $60 billion and passed the Better Utilization of Investments Leading to Development Act of 2018 (BUILD Act), which gives OPIC the authority to purchase equity in development projects, instead of merely providing loans.

The United States has also started to work in cooperation with Japan, Australia, and India to promote joint finance development projects in the Indo-Pacific region. During the 2018 APEC summit, for example, Vice President Pence announced that the United States would help Australia develop a naval base in Papua New Guinea (PNG) and work with New Zealand, Japan, and Australia to contribute to the development of PNG’s electrical power grid.

Other countries have also launched new infrastructure initiatives to compete with BRI. India and Japan, for example, announced the launch of a joint Asia-Africa Growth Corridor a few days after the Belt and Road Forum in May 2017, and the EU released its strategy for connecting Europe and Asia in September 2018.

BRI RECALIBRATION

In August 2018, Xi Jinping chaired a high-level symposium to mark BRI’s fifth anniversary. He compared the work already accomplished with the bold strokes of a Chinese freehand painting style called xieyi and declared that the time had come to shift to the gongbi style, in which the painter carefully traces the sharp details and fine lines. Responding to the increasing wave of discontent and criticism, he has set about to recalibrate BRI.

Specifically, Xi demanded that the needs and sensitivities of local governments and populations be better taken into account. In addition to big government-to-government projects, BRI would also focus on small-scale projects that respond to the immediate needs of local populations. People-to-people exchanges (education programs, tourism, and cooperation in science, technology, and culture) would be increased. In parallel, propaganda would focus on the positive impact of BRI projects on the daily lives of local populations.

Xi instructed the Chinese Communist Party to strengthen its leadership and oversight, particularly in risk assessment and mitigation. Chinese companies operating overseas must act as “BRI ambassadors,” making sure that their behavior and practices reflect well on projects that are “worthy of praise.”

THE NEXT PHASE: SECURING BRI?

As more Chinese banks and companies invest in and build BRI projects around the world, they will increase their global footprint, operate more businesses and engage in more commercial activities abroad, bring in more Chinese goods and workers, and export back to China more resources from areas that were until now largely outside its traditional reach.

BRI’s geographic scope extends over regions where the security situation has been increasingly volatile due to ethnic and religious violence, territorial disputes, and the destabilizing spillover from conflicts in Syria, Yemen, and Afghanistan. The central government has an ambitious vision and is determined to plow ahead, but the potential risks are undoubtedly high. This creates a conundrum for the Chinese military and security forces, which do not yet have the full capacity to project power far beyond China’s borders or to deploy forces in situations of high-intensity conflict.

In addition, China continues to abide by its long-standing principle of noninterference, which constitutes a real normative constraint on future overseas deployments. The question of how to protect the country’s growing overseas interests under BRI thus poses a new set of challenging requirements for the People’s Liberation Army and China’s security forces as a whole.

No comments:

Post a Comment