Raj Chengappa

Every Indian leader who occupied the spartan corner office in the prime minister's wing in Delhi's South Block after Jawaharlal Nehru, has looked to emulate him.

Every Indian leader who occupied the spartan corner office in the prime minister's wing in Delhi's South Block after Jawaharlal Nehru, has looked to emulate him.

Even Narendra Modi, though he may be loath to admit it in public. Modi's ideological moorings in the Rashtriya Swayamsewak Sangh (RSS) and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) have seen him spout venom against India's first prime minister and trash his achievements.

Yet, more than Indira Gandhi, it is Nehru's exalted status as the builder of modern India that every prime minister after him, including Modi, aspires to surpass. Do a Google search using the words 'Nehru' and 'books'.

Apart from the list of 50-odd books that he authored, including compilations of his speeches, it will throw up a thousand books written about him and his legacy. Such has been Nehru's prominence in the Indian mindspace.

As Modi completes five years as prime minister next month and seeks a mandate for a second term, he is clearly looking to establish a legacy of Nehruvian stature- the making of a Second Republic.

At the release of the BJP manifesto for the 2019 election, Modi didn't confine himself to listing out what his government and party would do up to 2024. Instead, he surprised everyone by setting goals far ahead-to 2047, when India completes a hundred years of Independence. He alluded to a vision of India as a developed country that would be a premier power in the world.

Modi then placed the work that his government had done so far and now promises to do in the next five years if re-elected as part of a process of achieving such a lofty vision. (If Modi follows his party's principle of leaders retiring at 75 years of age, he will have to do so in 2025 and will be out of the reckoning for breaking the record held by Nehru and Indira Gandhi of having the longest tenures as prime minister).

Unlike historians, ordinary citizens tend to judge political leaders by their defining moments rather than through a stringent assessment of their tenures. Their approach is binary and they can be brutally harsh when they lose faith in a prime minister.

Thus, Nehru is credited with laying the foundations of a new India but vilified for the humiliating defeat India suffered against China in the 1962 war. Indira Gandhi is best known for dismembering Pakistan in the 1971 war apart from making India a nuclear power in 1974 but she is remembered as much for imposing a disastrous Emergency between 1975 and 1977.

Rajiv Gandhi is regarded as someone who ushered in the computer revolution in India and a mission approach to development but evokes negative memories for the Bofors scandal and getting India embroiled in the Sri Lankan war. Narasimha Rao is lauded for bringing in economic reform, but slammed for allowing the Babri Masjid demolition on his watch.

Vajpayee is feted for his Kargil victory and nuclear tests but upbraided by many for failing to force Modi's resignation as chief minister after the 2002 Gujarat riots. And Manmohan Singh won appreciation for his record on economic prosperity and the nuclear deal in his first term but lost much of the goodwill when he presided over a government riven by allegations of scams and policy paralysis in his second term. When he left office, Singh hoped that history would judge him more kindly. It just may.

TO LAUD OR TO LAMBAST

So, how should we judge Modi's five-year record? Should we credit him with a Swachh Bharat revolution but decry him for failing to stem the agrarian crisis? Should we praise him for ushering in the biggest tax reform since Independence in the form of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) but criticise him for imposing a demonetisation drive to curb black money that ended up stunting India's economic growth? Then, again, should we laud him for drawing a new red line with Pakistan through his surgical strikes but blast him for the worsening situation in Kashmir? Should we commend him for running a relatively corruption-free government but castigate him for undermining the independence of institutions such as the Reserve Bank of India? Should we pat him on the back for building highways at breakneck speed but lambast his deafening silence over the murderous excesses of cow vigilantism?

(Note: the BJP's manifesto for 2019 makes no mention of steps to ensure greater protection for cows.) Should we hail him as amongst the most hardworking and energetic prime ministers the country has seen and yet censure him as his opponents do for his arrogance, his dictatorial tendencies and for the increasing concentration of power in the PMO?

As the leader of the world's largest democracy, every prime minister must be prepared to face more vilification than applause for their actions in office. That's because the buck stops with you, you can't pass the blame on to someone else. Modi is perceived to be sensitive to criticism and often complains that though he delivers, the goal posts are constantly shifted by those his cabinet colleague Arun Jaitley derides as "compulsive contrarians".

But Modi should heed the advice Chief Oren R. Lyons, faith-keeper of the Onondaga tribe and head of the Confederation of Native Americans, gave leaders who had assembled for the historic 1992 Earth Summit in Rio. Chief Oren said, "We were taught that every chief must have skin seven spans thick to withstand the barbs and arrows, mostly from his own people and not to hold counsel only for ourselves, our family or our generation. Every decision should reflect on the welfare of the seventh generation."

To the prime minister's credit, he always kept his sights and vision far ahead even as he contended with the problems he had inherited. When he took over in 2014, he was given a handsome majority in Parliament to provide a decisive government in contrast to UPA-II, revive economic growth, bring down inflation, ensure employment to millions (he had promised 10 million jobs annually), curb corruption and black money and speed up rural development.

He was seen as a prime minister in a hurry when he announced a flurry of government schemes and programmes (96 at the last count) to implement his promises with catchy slogans and deadlines that had historic significance. For the Swachh Bharat campaign that he announced in his first Independence Day address, he set October 2019 as the date for making India open-defecation free (ODF) to coincide with the 150th birth anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi. In the third year of his term, he was already looking at a second term when he talked of ushering in a new Bharat by 2022 when India completes 75 years of Independence. Not to mention his most recent refrain about looking ahead to 2047. Modi is undoubtedly a marathon runner, but he does not like to see himself in that light. In an informal interaction with this writer, he brushed aside such comparisons and said, "My focus is on sustainable development and every programme that my government initiates is to ensure that it contributes to a holistic growth that will last. My aim is to empower people to do it themselves."

A DETERMINED MIND

Nothing Modi does is random. It is linked to a larger scheme of things that he has in mind. He doesn't think small, he goes for scale. He is open to new ideas and has an eye for detail. But he shies away from revealing all the pieces of a plan at once as he worries that people who have to implement it might be overwhelmed by the task. Rural development became the hallmark of the way he got things done. He launched the Jan Dhan Yojana to open bank accounts to India's unbanked millions and soon linked it to the Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) scheme to transfer subsidies and relief funds directly to reduce pilferage and corruption. So the subsidy for a cooking gas connection and cylinders under the Ujjwala scheme is deposited directly in the beneficiary's Jan Dhan account. All these would be part of larger game plan where the government would fund houses for the poor (the government claims 15.9 million homes have been built since 2014 under the rechristened Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana), provide money for building toilets in that house from the Swachh Bharat kitty, the gas cylinder from the Ujjwala scheme and rural roads to provide connectivity under the Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana apart from a separate programme for electrification of households and villages. He also showed a commitment to clean energy, particularly solar. His efforts to use digital technology to monitor the schemes enabled far better implementation than before.

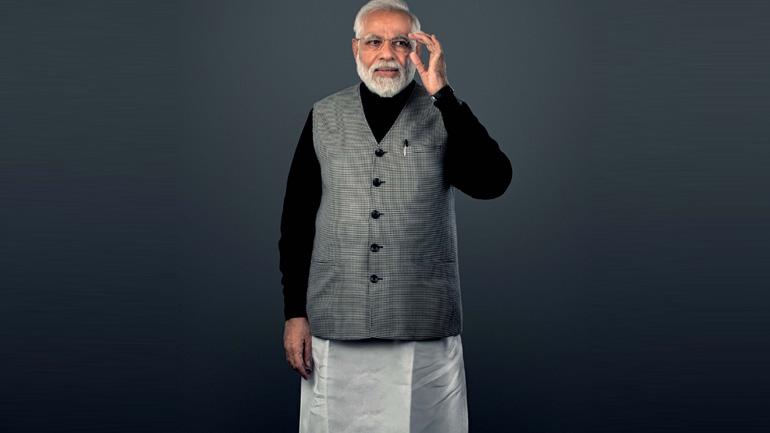

Nothing Modi does is random, it is linked to a larger scheme of things. He also doesn’t think small, he goes for scale. (Photo: Raj K Raj/Getty Images)

On another front, when Modi took over, he went about pulling the economy out of the morass it had sunk into in the final years of the UPA-II regime. Despite back-to-back droughts that hurt agriculture, the government, helped by record low oil prices, was able to fund massive infrastructure projects, particularly for building national highways (that came up at a rapid pace) and revamping the railways apart from funding rural development. Then hubris set in. To fulfil his campaign promise of putting an end to black money, he ordered the demonetisation of high value currency notes overnight on November 8, 2016. Far from meeting its primary objective, the move seriously damaged the vast unorganised and informal sector that ran on cash transactions, throwing millions, mostly the poor, out of jobs. The true impact would hit home when GDP growth dropped after demonetisation. Yet, bolstered by a landslide victory in the assembly election in Uttar Pradesh, Modi pushed ahead with implementing the GST. The combined effect of demonetisation and GST impacted job creation and stalled economic growth. The situation worsened because the banking sector, crippled with mounting non-performing assets (NPA), imposed a credit squeeze that further depressed growth in the manufacturing sector. It would take more than a year for the economy to recover and return to its GDP growth levels of 7 per cent annually.

Meanwhile, the Modi government had failed to gauge the enormity of the rural crisis that had built up. On agriculture, it had followed the policy of increasing productivity rather than boosting farmers' income. The glut in production may have kept inflation under control, but it brought farmers to their knees. Meaningful agrarian reform, including diversification of crops and setting up infrastructure to store and process produce, failed to take root. Adding to the woes, with manufacturing slowing down and the informal sector still in disarray after demonetisation, overall job creation dropped dramatically. However, the government continues to dispute employment figures.

Modi had a far better track record in his handling of foreign policy and national security issues even as the way his government dealt with Kashmir remains a blot. The prime minister's willingness to take tough action against Pakistan for terror attacks has bolstered his image, both domestically and internationally. That has emboldened the BJP to make zero tolerance on terror and national security the top priority in its manifesto for the 2019 election, ahead of even agricultural reform and job generation. This goes against the findings of the INDIA TODAY Political Stock Exchange poll which revealed that voters across the country considered unemployment the number one concern, followed by rural and farm distress and then national security.

THE MUSCULAR APPROACH

The BJP manifesto is focusing on three clear messages to win a second term for the Modi-led BJP government. Firstly, at the ideological level, by presenting itself as a muscular, nationalistic party and pushing for the Ram Mandir in Ayodhya, a uniform civil code and abolishing Article 370, the BJP hopes to retain the support of its Hindutva core constituency. Secondly, at the social level, to address agrarian distress, the BJP has expanded the scope of the annual Rs 6,000 dole to all farmers instead of only to those who own less than two hectares in a bid to counter the Congress promise of a minimum guaranteed income of Rs 6,000 per month to all households below the poverty line. While repeating the anodyne promise of doubling farmers' incomes that it had talked up about mid-way through its current term, the party is short on details on how to do so except for committing an investment of Rs 25 lakh crore to improve the sector. Thirdly, at the economic level, the BJP flatly refuses to acknowledge that there is a jobs crisis at all and, surprisingly, only discusses employment under the header 'Creating Opportunities for Youth'. The manifesto does talk of pumping Rs 100 lakh crore as capital investment in infrastructure, which it hopes will also energise the manufacturing sector and generate employment.

Modi clearly believes his credibility as a leader who can deliver is much more powerful than any of the promises made by the Congress and other parties. On the stump, his connect with the people is obvious and he remains his party's biggest vote-getter. He summed up his pitch for a second term thus: "In our first term, we focused on meeting the basic needs of the people; in the second, we will focus on fulfilling their aspirations." So confident is Modi of being re-elected that apart from fixing his schedule of foreign trips in September, he has formed committees to come out with a 100-day action plan for his second term. Those who work with him closely say that five years at the helm have made him no less impatient to get things done. As one of them put it, "He still wants all the work he assigned to be done yesterday rather than today. We can't match his enthusiasm for speeding up national development. The emphasis in his second term will be on deeper reforms." It is now left to the 900 million voters in India to give their verdict on the Modi government's performance and decide whether he deserves a second term as prime minister.

No comments:

Post a Comment