By Tamim Asey

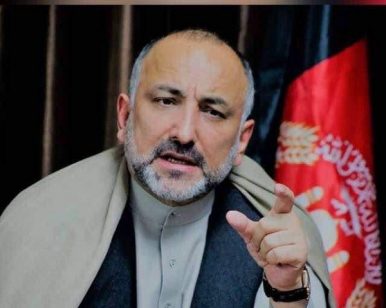

As Afghanistan’s national security adviser, Mohammad Haneef Atmar signed the Bilateral Security Agreement (BSA) with the United States, negotiated a peace agreement with Hizb-e-Islami Group (HIG), kept a fragile regional consensus on Afghan war and peace intact until his departure, and undertook major reforms in the Afghan security sector. Today, he is running for the highest office in Afghanistan, challenging his former ally, Mohammad Ashraf Ghani, for the presidency.

As Afghanistan’s national security adviser, Mohammad Haneef Atmar signed the Bilateral Security Agreement (BSA) with the United States, negotiated a peace agreement with Hizb-e-Islami Group (HIG), kept a fragile regional consensus on Afghan war and peace intact until his departure, and undertook major reforms in the Afghan security sector. Today, he is running for the highest office in Afghanistan, challenging his former ally, Mohammad Ashraf Ghani, for the presidency.

Ghani, increasingly paranoid and isolated, has become a divisive personality both at home and abroad. The Afghan political elite do not trust him, his former allies have left his side, and the region increasingly views him as a puppet — too westernized, removed from the Afghan realities, and distanced from its people.

Atmar, a British-educated former spy turned humanitarian worker and politician, is one of the most formidable figures to challenge the incumbent Ghani in the upcoming presidential election. The late Richard Holbrooke once dubbed Atmar as the next president of Afghanistan, and most of the European and American generals who worked with him over the years considered him as a man to count on during a crisis. He was the go-to man for many in the international community and the region on issues ranging from women’s rights to building regional and global consensus on the Afghan peace process.

In one telling episode, a former European ambassador burst out of a meeting with the Afghan president, terming it a repetitive lecture with no end in sight. The frustrated diplomat instead heading next door to meet Atmar for consultations on an important European agreement to fund the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces (ANDSF). The ambassador was frustrated by the lack of results from Ghani; Atmar, he knew, would carefully take notes and get back to him with progress in a few days. Such was the reputation of Atmar in the National Unity Government.

Prior to his role as the national security advisor of Afghanistan, Atmar was a successful businessman and the head of a major political party, the Rights and Justice Party, which gathered moderate and Western-educated Afghans to advocate for the political and human rights of all Afghans. Former U.S. Ambassador Karl Eikenberry called Atmar’s party one of the most progressive parties of post 9/11 Afghanistan. Meanwhile, his business, Hambastagi Co., was flourishing with a portfolio of projects amounting to millions of dollars and employing hundreds of Afghans and dozens of foreigners.

Atmar also had a long and distinguished career in the Afghan humanitarian and development community as well. He headed several NGOs such as the International Rescue Committee and Norwegian Church Aid during the reign of the Taliban and traveled across Afghanistan to deliver humanitarian aid and development projects. Many of his colleagues even then regarded him as a broker, negotiator, and excellent project manager who enjoyed the trust of Afghans and donors. He is a man who has seen many faces and many chapters of Afghanistan; today he wants to put that experience and knowledge in use in the Afghan presidency.

Atmar brings to bear some unique qualities in this race: unity, pluralism, inclusivity, and above all a desire for broad-based change and reform in the culture of politics in Afghanistan. During his time in office, Atmar served as the unifier, firefighter, and glue holding the fragile and shaky National Unity Government together. For days on end, he would shuttle between the office of the president and the office of the chief executive to settle their differences and call for unity. His shuttle diplomacy did not end within the Afghan government but also extended throughout the region. He was often traveling to the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Russia, Iran, and Central Asian states to urge them to cooperate rather than compete in the Afghan war and peace theater, present confidence building measures, and listen to and address their concerns.

Atmar hails from Kandahar and speaks Kandahari Pashtu with a thick accent. The same region is the birthplace of the Afghan Taliban, a factor that goes a long way in the complicated web of Afghan tribal politics. He is well-known to the Afghan Taliban since his days as a humanitarian worker and subsequently during his many assignments in former President Hamid Karzai’s cabinet, where he kept channels open with the Afghan Taliban for negotiations. When Karzai invited Taliban negotiators, messengers, and leaders for negotiations in Kabul, they often ended up meeting Atmar for advice and assistance. Today, the United States and the West need such a man with Atmar’s skill set and proven track record to allow for a graceful exit by American forces, forge a regional consensus and negotiate a peace deal with the Afghan Taliban, and pave the way for a peaceful and stable Afghanistan.

Tamim Asey is the former Afghan Deputy Minister of Defense and Director General at the Afghan National Security Council. He is currently pursuing a Ph.D in Security studies in London. Follow him on Twitter @tamimasey.

No comments:

Post a Comment