By Jack Thompson

Jack Thompson contends that the US’ longstanding role of international leadership is under threat. Washington is struggling to manage external challenges —including great power competition and globalization— and domestic constraints, such as the underfunding and mismanagement of the military and diplomatic corps. Unfortunately, prospects for reform are uncertain given the dysfunctionality of the US political system. So what does all this mean for the future of US foreign policy? Further, what implications could this have for European policymakers? Here’s Thompson’s answer.

Jack Thompson contends that the US’ longstanding role of international leadership is under threat. Washington is struggling to manage external challenges —including great power competition and globalization— and domestic constraints, such as the underfunding and mismanagement of the military and diplomatic corps. Unfortunately, prospects for reform are uncertain given the dysfunctionality of the US political system. So what does all this mean for the future of US foreign policy? Further, what implications could this have for European policymakers? Here’s Thompson’s answer.

The US’ longstanding role of international leadership is under threat. It is struggling to manage external challenges, including great power competition and globalization, and domestic constraints, such as underfunding and mismanagement of the military and diplomatic corps. Unfortunately, prospects for reform are uncertain given the dysfunctionality of the US political system. This should worry European policymakers and will hopefully hasten their efforts to develop a more robust and independent Common Security and Defense Policy.

Introduction

The United States enjoys an unrivaled ability to shape world affairs. Thanks in large part to its leadership of and participation in the liberal world order (LWO), US military might is unequalled, its economy is the largest in the world, and the US dollar’s status as the most important reserve currency provides enormous benefits. Soft power is another area of advantage, with US culture in particular commanding global influence.

US President Donald Trump returns to the White House after addressing the Republican Congressional Retreat, 1 February 2018. Yuri Gripas / Reuters

However, this favorable state of affairs is under threat. Partly, this is due to structural changes in the international system. With the rise of persistent global and regional challengers, the post-Cold War “unipolar moment” has ended, and US military and economic predominance are no longer assured. Globalization and technological change have accelerated the process, fragmenting power, diffusing information, and weakening support for international trade and democratic values. Even its soft power could be at risk, as political and economic dysfunction undermine the US’ image abroad.

If the US is to reverse these trends, to retain a position of unquestioned leadership in world affairs, and to preserve the LWO, it will need to get its house in order. There is little policymakers can do to reverse the structural changes to the international system, but they have the power to deploy US troops more carefully, to manage the military and diplomatic corps more intelligently, and to address the underlying causes of opposition to international trade and declining attachment to democratic norms.

Unfortunately, a vigorous reassertion of US leadership appears to be unlikely. Demanding deployments and – in light of its many commitments – inadequate budgets have left the military in a state of crisis. The diplomatic corps is also struggling under the weight of poor leadership, a sharp reduction in numbers, sinking morale, and the prospect of reduced funding. Some of these problems are specific to Donald Trump’s presidency, but the problems go much deeper than the current administration.

In other words, reform is unlikely. There is little indication that the political will exists, or that the system is equipped to accommodate the sweeping changes that would be necessary to turn things around. Washington remains hamstrung by gridlock, which reflects the polarization that has divided society in recent decades. It seems likely that the US will continue to face significant constraints for the foreseeable future. In the meantime, its rivals are gaining ground, and the world is becoming less conducive to liberal internationalist values such as democracy, free trade, and the rule of law. This state of affairs should worry Europeans, as their foreign and security policy relies upon vigorous international engagement by the US.

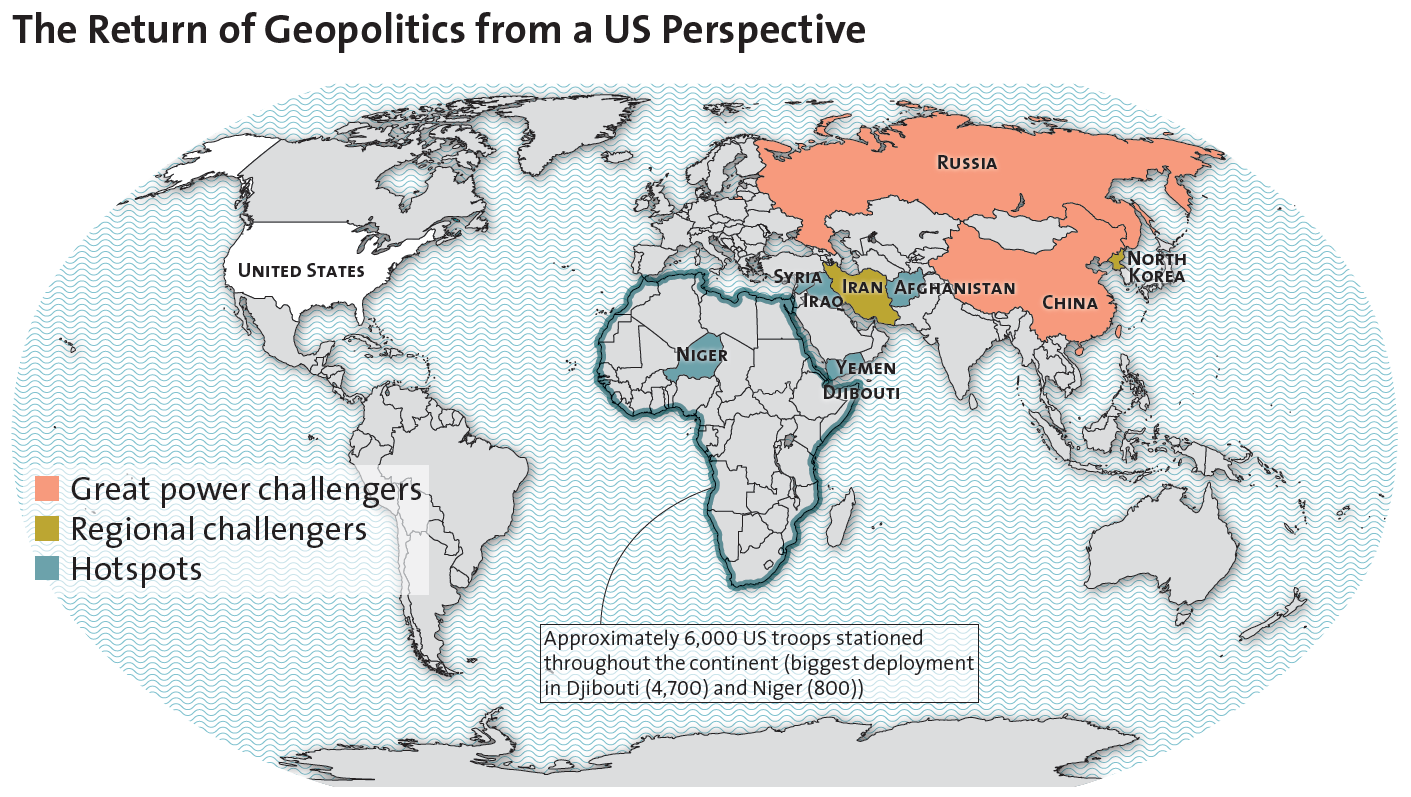

Sources: Kathryn Watson, “Where does the U.S. have troops in Africa, and why?”, in: CBS News (21.10.2017); International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), The Military Balance 2018 (Routledge, 2018), 59.

The Return of Geopolitics and the Forever War

The apparent post-Cold War triumph of the LWO has proven illusory. Instead, the US and its allies face a fractured, multipolar system that is rife with threats, especially from revisionist powers. What Walter Russell Mead dubbed the “return of geopolitics” represents – as the Department of Defense’s 2018 National Defense Strategy acknowledges – “the primary concern in U.S. national security”.

Two nations, China and Russia, have not reconciled themselves to the current international order and constitute the foremost threat to US leadership and the future of the LWO. China resents US predominance and is positioning itself as a rival superpower. Though Beijing is challenging US interests across the globe, its priority is to upend the status quo in East Asia, where the US has long served as the fulcrum for the region’s power structure. Much as the US asserted itself in the Western Hemisphere in the early 20th century by forcing European nations to acknowledge its preeminent role, China seeks to replace the US as the leading power in its neighborhood.

Though the US position remains strong, recent political and economic developments have drawn attention to Beijing’s growing influence. President Trump’s decision to withdraw the US from the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade agreement – which excluded China, and which the administration of Barack Obama viewed as a way to reinforce its standing in East Asia – represented a setback. China quickly moved to fill the vacuum by redoubling efforts to promote an alternative arrangement, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership. This dovetails with a desire to link Eurasia under Chinese economic leadership, embodied in the Belt and Road Initiative, and a long-term goal of establishing footholds in Europe, Latin America, and Africa.

Beijing is also challenging the US and its allies on military, strategic, and technological fronts. It is executing a steady campaign of pressing a long list of territorial claims in the region, including a dispute with Japan over the Senkaku Islands. Even more noteworthy is China’s project of creating artificial islands in the South China Sea, several of which it is equipping for military purposes. Their development also serves the broader goal of buttressing Beijing’s claim to sovereignty over most of the South China Sea, the world’s most important shipping zone. The US contests this claim by regularly conducting freedom of navigation exercises, but has been unable to do anything to slow the reclamation and fortification project. China’s development of anti-ship ballistic missiles, which are designed to destroy aircraft carriers, also threatens the ability of the US to intervene in the region. China’s nuclear arsenal, though still small when compared to those of the US or Russia, is slowly increasing in size and in terms of its capabilities.1

China has moved aggressively to close the gap with the US in the realm of advanced technology, with considerable success. When it comes to artificial intelligence, for instance, China has announced a goal of becoming the global leader by 2030, and is already closing in on the US. China is also a powerful player in the cyber domain and is using its influence to shape the global development of the internet in ways that are conducive to its own interests, but not necessarily to those of the West.2

Like China, Russia seeks to undermine US leadership, which it views as the foremost hurdle to its return to superpower status. Vladimir Putin’s campaign to revivify Russian power has enjoyed considerable success, even if the economic resources at his disposal are more modest than China’s, and much of his progress has come at the expense of the US and its allies. Military interventions in Georgia and Ukraine – nations that harbored ambitions of drawing closer to the European Union (EU) and/or the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) – elicited condemnation and economic sanctions from the West. However, these have done nothing to impair Moscow’s aggressiveness, which includes frequent violations of NATO airspace. Even Moscow’s interference in the 2016 US elections, the full extent of which remains unclear, has yet to elicit an effective US response.

Russia’s intervention in the Syrian civil war appears to have been a decisive factor in the resurgence of Bashir al- Assad’s regime and should give Moscow a foothold in the Middle East for the foreseeable future. Meanwhile, in spite of the virtual defeat of the Islamic State, the return on Washington’s investment of money and troops in Syria has been more modest. Nevertheless, former Secretary of State Rex Tillerson recently announced that US forces will remain in Syria for the foreseeable future, thereby adding further strain to an overstretched military.

The US is also confronted by regional powers that resent the status quo. The speed with which North Korea has developed intercontinental ballistic missiles that might already be able to reach the US mainland, and Pyongyang’s unwillingness to trade its nuclear weapons program for relief from economic sanctions, has left policymakers with a series of unappealing choices. They could accept North Korea as a nuclear power and rely on deterrence. However, Kim Jong-un’s regime is particularly brutal and regularly transgresses international laws and norms. It views a nuclear arsenal as more than merely a defensive investment. Rather, it has a history of engaging in brinkmanship to extract concessions from the US and the rest of the international community.

One alternative to deterrence would be an attack designed to destroy most or all of the North Korean nuclear arsenal. The Trump administration is currently considering such a “bloody nose” strike. However, even if a military raid achieved its objectives – and the chances of success would be low – Pyongyang also has extensive conventional armaments at its disposal. These includes a large array of artillery that potentially could inflict catastrophic damage upon Seoul.3 A third option, relying on North Korea’s only close ally, China, to force Pyongyang to denuclearize has also failed. There are limits to Beijing’s ability to dictate to North Korea and it is unwilling to impose conditions that would lead the Kim regime to collapse, as the most likely outcome would be a united Korea closely allied to the US.

Policymakers are also uncertain how to handle the emergence of Iran as a regional power. The 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) appears to have halted Iran’s nuclear weapons program. However, the president and some of his key advisors have taken initial steps to undermine the JCPOA, and there are indications that they will withdraw from it altogether.4 Meanwhile, Iranian influence in the Middle East continues to increase. Tehran’s expansion has been enabled, in large part, by ineffective US policy over the last 15 years, including the invasion of Iraq in 2003 and the indecisive response to the Syrian civil war.

There are no appealing options when it comes to restraining Iran. The Trump administration complains that the JCPOA, by ignoring the non-nuclear aspects of Iranian expansionism, is worse than no deal. However, withdrawing from the JCPOA would alienate the other signatories – especially the Europeans, who consider the deal to be effective – and allow Iran to restart its nuclear weapons program. The preferred alternative of some hawks – airstrikes on Iran’s nuclear facilities – would further destabilize the region. It would also be difficult to hit all of the targets, and even a successful operation would only retard Tehran’s nuclear program for a few years.5

The Trump administration’s attempt to balance Tehran by reinvigorating the long-standing alliance with Saudi Arabia and moving even closer to Israel also brings risks. By siding so decisively with Riyadh and Tel Aviv, the US further undermines its previous status as an honest broker and makes a broader peace agreement in the region between Israel and its neighbors more unlikely. This strategy also ties the US more closely to Saudi Arabia’s disastrous intervention in Yemen, which will do nothing to improve the US’ image in the region.

US troops have been involved in combat in the Middle East and South/ Central Asia for more than 15 years, and the recent announcement of the Trump administration that it is planning for an open-ended commitment of forces in Syria confirms that there is no end in sight to the “Forever War” against terrorism and hostile regimes. The length of this conflict, which constitutes the longest in US history, does not indicate resolve. Instead, it underlines the inability of the US to obtain its political and military objectives, or even to formulate a coherent strategy for doing so. The prosecution of the Forever War has led to an unsustainable dynamic: The US is fighting on too many fronts and lacks the resources and political will to maintain the present situation. It is a textbook example of imperial overstretch.

If anything, the situation is worsening. Military involvement in Africa is a case in point. It has notably escalated over the last 15 years and now affects almost every nation on the continent. Many soldiers – at least 6,000, according to the Department of Defense – are participating in ill-defined activities such as training or advising, which often entangle them in combat.

Obama was anxious to avoid worsening the problem of overstretch, and Trump, albeit inconsistently, has also criticized the Bush administration’s overuse of the military. Yet neither has explained how to prevent it. This suggests that the US is caught in a vicious cycle. Policymakers recognize that they need to use force more intelligently in order to husband finite resources and revitalize an exhausted military, but struggle to extricate the US from its existing obligations. Furthermore, the temptation to intervene in new hotspots is ever-present.

The Downsides of Economic Interdependence and Globalization

In the decades following World War Two, the US did more than any other nation to create the foundations of the modern era. It encouraged free trade and the lowering of barriers to the flow of capital; US corporations penetrated new markets, taking knowledge and technology with them; and millions embraced US popular culture. The results appeared to be unequivocally positive. Many Americans attained unprecedented standards of living as a result of greater interdependence, and the US economy remains the world’s largest and arguably most dynamic.

Nevertheless, in the years since the financial crisis of 2007 – 2008 the downsides of globalization have become apparent. Indeed, even as the US appears to be thriving, it is also increasingly constrained by many of the forces it was instrumental in unleashing. In spite of strong headline numbers – including an unemployment rate of approximately 4 per cent and an economic expansion of 2.3 per cent in 2017 – there is ample reason for concern. Partly, this can be ascribed to ineffective policymaking at home. Inequality has reached historic levels, and legislators appear to be more concerned with placating wealthy donors than with the need to rebuild crumbling infrastructure or make university education more affordable.6

Changes in the structure of the global economy also present long-term obstacles. The rise of China – facilitated in part by the interdependence pursued by the US – is particularly problematic. In and of itself, the emergence of a strong economic counterweight is not necessarily cause for concern. The economic clout of allies such as Germany, Japan, or the EU – in spite of occasional alarmist headlines – does not generate widespread alarm. However, the threat posed by China is more profound: it is expected to surpass the US as the world’s largest economy in the near future, and its ability to influence the global system dwarfs that of other trade competitors.

The scale of China’s influence can be seen in the consequences of its rapid growth. The “China Shock”7 – the inability of labor markets to adjust to competition from China – and other manifestations of interdependence, such as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), have led to the loss of millions of jobs, the long-term decline of regions most vulnerable to increased competition, and an increase in political populism, including calls for protectionism.

The nature of the Chinese regime and its geopolitical ambitions also make its status as an economic superpower problematic. In spite of occasional friction between the US and Germany or Japan over trade practices, the fact that they are close allies that hold free elections and embrace the rule of law means that they pose no threat to core US interests – a point that is lost on President Trump. China, by contrast, has failed to democratize. This has confounded many analysts, who argued that accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001 and a long-term program of economic liberalization would force Beijing to reform its political system. If anything, the opposite has occurred, and President Xi Jinping has redoubled the grip of the Communist Party, as well as his own, on the Chinese political system.

This combination of economic power and resilient authoritarianism gives Beijing considerable global sway.8 China is now Africa’s largest trading partner and, in spite of Beijing’s official policy of “non-interference” in the internal affairs of other countries, it has gradually expanded its influence throughout the continent. In doing so, it has pursued strategic aims – such as garnering support for its “One China” policy and its model of non-democratic governance – as well as economic growth.9 Similar efforts in Latin America pair economic and strategic objectives, such as counterbalancing the strong position of the US in East Asia.10

Most worrying is China’s growing influence in Europe. It has used promises of investment in the “16+1” group of Central and Eastern/Southeastern European countries to engender closer ties and more sympathy on issues such as human rights.11 While China’s influence is still modest in comparison to that of the US – and is generating opposition in some corners of Europe – its efforts underscore the sweeping scale of Beijing’s vision. Furthermore, China’s emergence as an alternative to the US when it comes to leading the international community on pressing global challenges, such as trade liberalization or combating global warming, underscores the fact that the US can no longer take predominance for granted.

Regional powers have also harnessed aspects of globalization to increase their ability to frustrate the US. North Korea and Iran have used technology first developed in the West in their quest to attempt to develop nuclear arsenals. North Korea has developed sophisticated cyber capabilities and used them to carry out cybercrime, to infiltrate the political and military infrastructure of adversaries such as South Korea, and to undermine the dissemination of what it views as hostile cultural products. The US has yet to develop an effective response.12 Because its economy is relatively primitive, retaliatory attacks are of limited value, and until recently, the US has been reluctant to respond with conventional military force for fear of sparking a broader conflict.

Hostile powers and non-state actors alike have discovered that some of the longstanding strengths of the US, such as its democratic form of government and the ability to develop and integrate advanced technology into its economy, render it vulnerable to cyber attacks. Russia’s interference in the 2016 election relied on a combination of cyber espionage and collaboration with US citizens. WikiLeaks has caused considerable damage by releasing a large number of sensitive government documents. These data dumps, which have relied on leaks from inside the US national security community and intelligence acquired by state actors such as Russia, have angered allies and damaged US soft power.

As the example of WikiLeaks indicates, globalization has enabled some non-state actors to accrue disproportionate influence. The ability of terrorist groups such as al-Qaida or the Islamic State to confront the US would not have been possible in the era before modern international travel, mass immigration, and wider access to information about weapons and military tactics. The tendency of the US to overreact, and to pay correspondingly less attention to more acute problems such as global warming, only compounds the problem.

Domestic Constraints

Trade liberalization and advances in technology have had a profound impact on US political culture. Political polarization, for instance, has increased in areas that are exposed to increased international trade. Over the last 15 years, congressional districts represented by moderates have tended to replace them with more liberal Democrats or more conservative Republicans. In presidential races, these areas have become more likely to vote for Republican candidates.13 The results at the national level are striking, as polarization has reached historically high levels and the Republican Party (GOP) is more conservative than at any point in its history.14

Related to this increase in partisanship is the tendency of voters who have suffered economically as a result of free trade and/or technological change to embrace radical political views. Many working-class white voters feel that they have lost economic and political status and power.15 This perception has been amplified by the growing diversity in the US – at some point in the mid-21st century, whites will no longer constitute of a majority of the population – and has fueled support for extremist political ideas and figures, with several notable consequences.

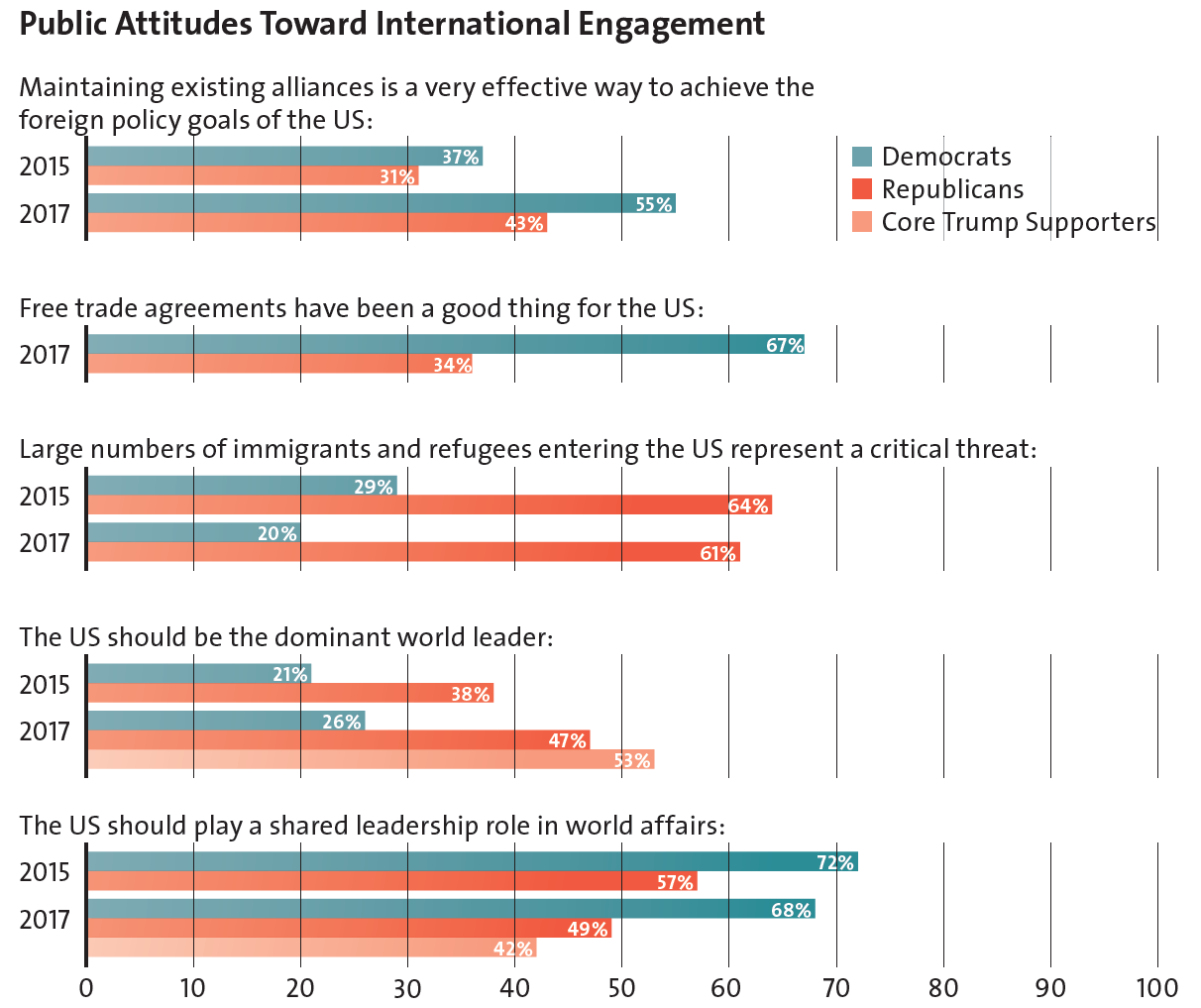

One is decreased enthusiasm for democratic politics and norms – which correlate closely with support for internationalism. This phenomenon is particularly notable among younger Americans, but can be seen throughout the US body politic.16 The rise in authoritarian values – a preference for order and conformity, especially in times of crisis – and the growing tendency of authoritarians to vote for the GOP, is a manifestation of this tendency.17 Another is the radicalization of border politics, as a majority of white Americans have come to view immigration as a burden and/or threat.18 Opposition to free trade has become an important feature of US politics, especially among culturally conservative whites.19 Support for international alliances is shaky and notably weak among Republicans (though support for NATO remains strong). Even when it comes to broad attitudes toward international engagement, which a large majority of Republicans advocate, many in the party – and a majority of Trump supporters – prefer a dominant position rather than a shared leadership role.20

Sources: Dina Smeltz et al., “What Americans Think about America First”, in: 2017 Chicago Council Survey, The Chicago Council on Global Affairs (2017), p. 3, 5, 9; Dina Smeltz et al., “America Divided: Political Partisanship and US Foreign Policy”, in: 2015 Chicago Council Survey, The Chicago Council on Global Affairs (2015), p. 12; Bradley Jones, “Support for free trade agreements rebounds modestly, but wide partisan differences remain”, Pew Research Center (2017).

When viewed in this light, the election of Donald Trump is not surprising. His withdrawal from the Trans- Pacific Partnership trade agreement; his promise to renegotiate or withdraw from NAFTA and to get tough on Chinese trade practices; his attempts to reduce the number of immigrants, legal and undocumented alike; his ambivalence about NATO; his enthusiasm for illiberal leaders; and his reluctance to condemn white supremacists – all of these policies are acceptable to millions of Americans, and in some instances enjoy the support of a majority of Republican voters. Many in the GOP political establishment have quickly embraced the Trumpification of Republican foreign policy. (It is also worth noting that in regard to some aspects of international engagement, such as free trade, a large minority of Democratic voters also express skepticism.)

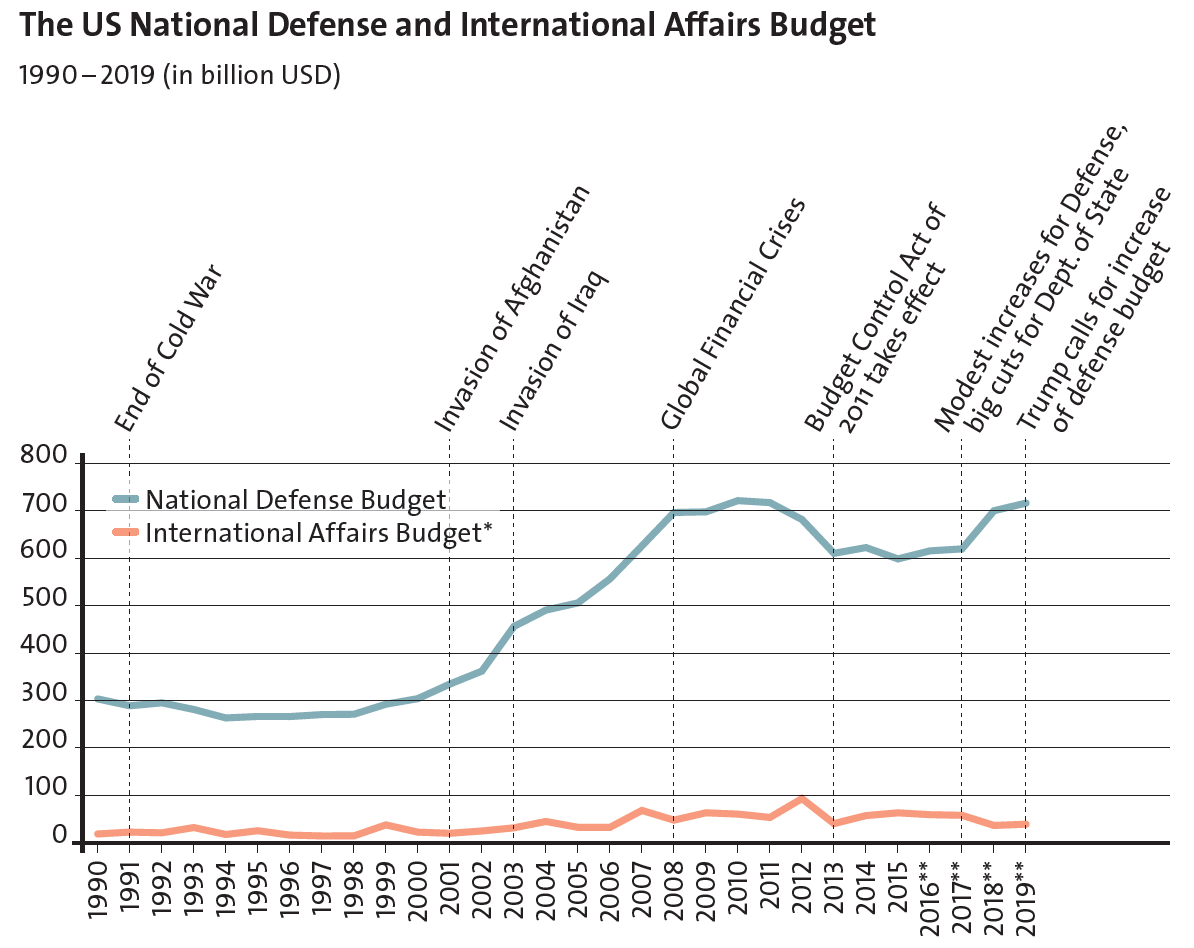

Overstretch, polarization, political dysfunction, and skepticism about internationalist policies have contributed to a crisis in funding and readiness for the military. The problem began with the conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq, which led to frequent and lengthy deployments for many soldiers and a corresponding drop in morale. This problem has been compounded by certain provisions in the Budget Control Act of 2011 – commonly referred to as sequestration – which was opposed by most members of Congress, but was nevertheless implemented because no agreement could be reached to fund the government. Sequestration has required substantial spending cuts and led to uncertainty about long-term funding streams.21

President Trump has called for a sustained increase in military spending, including an upgrade and expansion of the nuclear arsenal that will cost at least 1.2 trillion USD. Although Congress recently agreed to a spending deal that would increase funding for the military over the next two years by 160 billion USD, this is unlikely to include nuclear weapons. Furthermore, though the additional funding is a necessary first step, it will still take time to undo the damage wrought by sequestration. For instance, in the event of a conflict, the Army would only be able to field an estimated three brigade combat teams out of more than 50.22

The diplomatic corps is also in a state of crisis. At one per cent of the federal budget, funding for the Department of State and the Agency for International Development is already modest. To make matters worse, the Trump administration has proposed sweeping cuts to these departments – though Congress is unlikely to approve these reductions in full. This indifference to the importance of diplomacy and development, along with mismanagement by former Secretary of State Tillerson, has resulted in a steep decline in morale and a mass exodus of senior diplomats. Meanwhile, a hiring freeze by Tillerson has dramatically lowered the number of incoming Foreign Service Officers.23

With the exception of the ongoing disaster at the State Department, it would be a mistake to blame Trump for these developments. Rather, the president embodies an evolving political culture in which actual or perceived threats assume disproportionate importance for many. This imposes additional constraints on foreign as well as domestic policy making and makes it more difficult to sustain internationalist policies such as admitting immigrants, promoting trade deals, maintaining alliances, and upholding democratic values.

* International Affairs Budget consists of International Development and Humanitarian Assistance, International Security

Assistance, Conduct of Foreign Affairs, Foreign Information and Exchange Activities, International Financial Programs

** Estimate

Sources: U.S. Government Publishing Office; Paul Singer, “What’s in the senate budget deal? Billions for defense, infrastructure, disasters and more”, in: USA Today (7.2.2018).

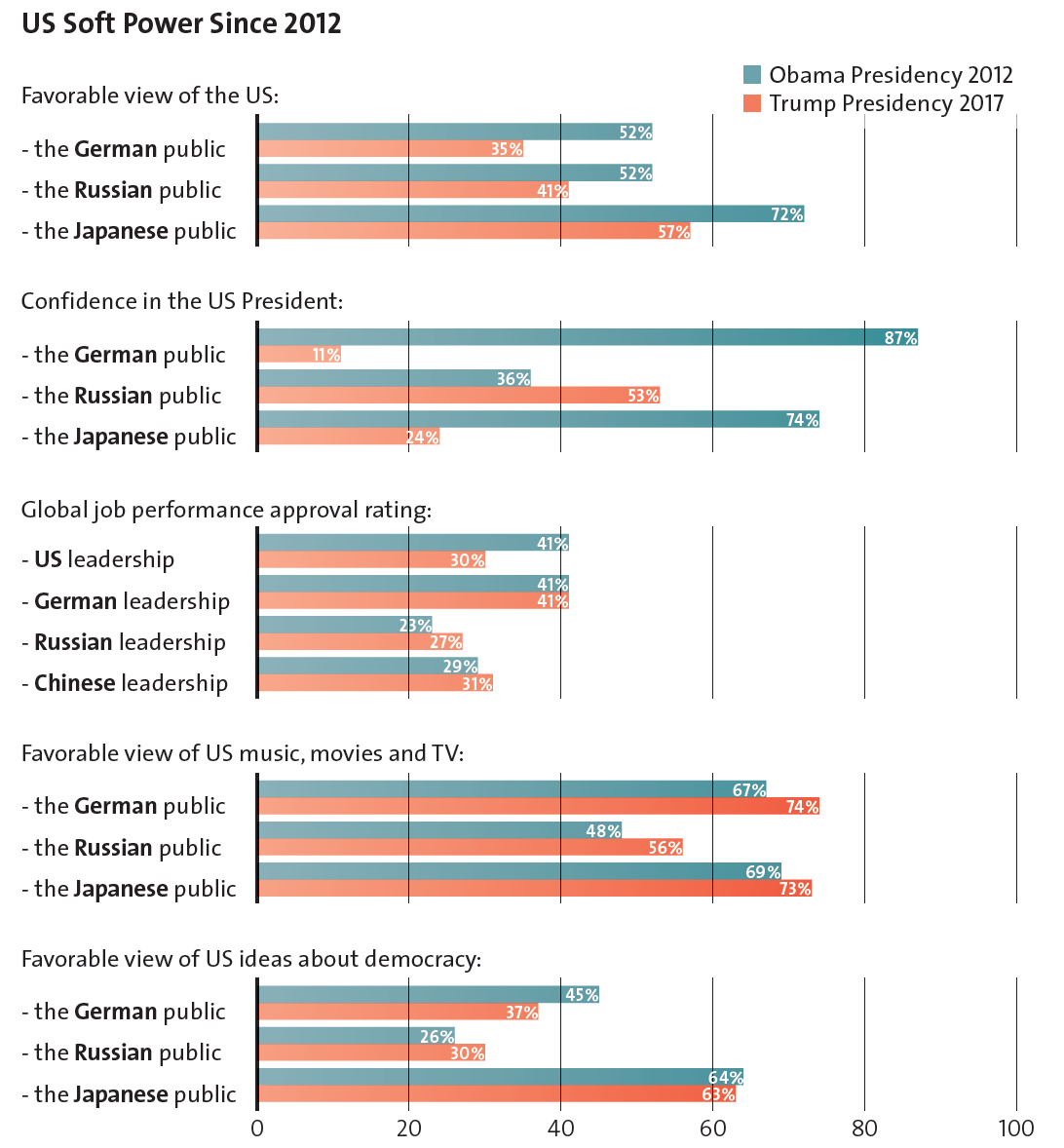

The rest of the world has noticed. Although there is still widespread admiration for some aspects of the US, such as popular culture, there is widespread unease about its political system and opposition to the spread of its ideas and customs. Partly, these attitudes can be linked to the election of Trump, who is unpopular in all but a few countries.24 It is also evidence of a wider sense of disquiet about the future of US global engagement. Approval of US leadership worldwide rose between 2008 and 2016, but has since returned to the low levels that prevailed during the Bush administration. It now ranks on par with China, a troubling omen for those who consider US soft power to be an advantage in its rivalry with Beijing. Also worrying is that only one-quarter of Europeans approve of US leadership.25

Sources: Andrew Kohut et al., “Global Opinion of Obama Slips, International Policies Faulted”, Pew Research Center (2012), p. 3, 5, 22 – 23; Richard Wike et al., “U.S. Image suffers as Public Around World Question Trumps Leadership”, Pew Research Center (2017), p. 22, 28, 34, 93 – 94; Gallup (2018), Rating World Leaders: 2018, p.2.

Conclusion: the Consequences of Constraint

Policymakers face a different geopolitical landscape than their post-World War Two predecessors. The US remains the world’s most powerful nation, but its influence is undermined by foreign and domestic constraints that are unlikely to dissipate. Great power competitors such as China and Russia will remain antagonistic – though China, given its economic strength, has a much better chance of sustaining its challenge over the long term.

The downsides of globalization will also endure. Economic interdependence, a source of considerable strength for the US economy, will also continue to fuel inequality and – in combination with cultural conservatism – political radicalization. There is little reason to expect that the political will exists to address this paradox, or that the system is even capable of accommodating the type of changes that would be necessary. On the contrary, the situation appears set to worsen, as key arms of the US foreign policy and national security apparatus – its military and diplomatic corps – are in the midst of crises that could leave them hobbled for years.

Aspects of soft power, such as popular culture and the reputation of its leading universities, will continue to be a strength, but the longer the US is plagued by political dysfunction and radicalization the more difficult it will be to attract talented foreigners and influence other nations. One worrying sign is that after years of steady growth, enrollments by international students at US universities declined in 2016 and 2017.26

Meanwhile, the diffusion of information and technology will continue to empower regional competitors and non-state actors. Here, too, policymakers remain at a loss as to how to respond. The nature of the US economic and political system, with its reliance on the rule of law, advanced technology, and the free flow of information and people, leaves it uniquely vulnerable to asymmetric attacks from weaker and authoritarian foes. Partisanship further complicates matters by making it difficult to assess the impact of previous attacks and to implement effective countermeasures.

What does all of this mean for the future of US foreign policy? Sweeping predictions are unwise in the era of Trump, but the evidence suggests several trends. Fears that the US will embrace a form of neo-isolationism are unjustified. However, we can expect more extreme swings in behavior, based partly on which party holds power. The GOP has fused comfortably with Trumpism, leaving it more nationalist and unilateralist than was previously the case – a fact which is highlighted by the administration’s decision to continue using the unsavory phrase “America First”, which appears numerous times in the recently released National Security Strategy. This means it will be prone to bouts of protectionism, nativism, xenophobia, and illiberalism. This will hamper efforts to sustain an internationalist grand strategy in the coming years. The Democratic Party, meanwhile, continues to be more committed to engagement, multilateralism, and democratic values. However, a vocal minority of the party firmly opposes trade liberalization and favors further cuts in military spending – tendencies which bode poorly for revitalizing US leadership.

In the worst-case scenario, extremist nationalism combined with an inability to satisfactorily counter asymmetric threats could lead to a more dangerous, unpredictable foreign policy. One hint of this troubling possibility can be found in the 2018 Nuclear Posture Review (NPR). It expands the category of threats that could elicit a nuclear response and calls for placing more emphasis on low-yield devices. Obama’s 2010 NPR called for modernizing the nation’s nuclear arsenal, but also sought to lead the way on arms control. In keeping with his skepticism regarding the value of international cooperation, Trump shows no such interest.27

European policymakers are understandably concerned about the direction of US foreign policy. It is more aggressive but less effective, and more demanding of its allies but unwilling to provide leadership. This state of affairs presents potential opportunities and pitfalls. The return of geopolitics will focus US attention on Africa, the Middle East, and East Asia, leaving limited time and resources for assisting allies across the Atlantic. This could encourage Europe to accelerate the development of a robust Common Security and Defense Policy (CSDP) and, in the best-case scenario, lead to a more equal and fruitful US-European relationship.

However, if the US continues to struggle to adapt to the evolution of global politics and to address its most pressing domestic challenges, the transatlantic alliance will suffer accordingly. This would be dangerous for both sides – and for the entire international system.

No comments:

Post a Comment