Zack Whittaker

In a rare move, government officials have handed security researchers a seized server believed to be used by North Korean hackers to launch dozens of targeted attacks last year.

In a rare move, government officials have handed security researchers a seized server believed to be used by North Korean hackers to launch dozens of targeted attacks last year.

Known as Operation Sharpshooter, the server was used to deliver a malware campaign targeting governments, telecoms, and defense contractors — first uncovered in December. The hackers sent malicious Word document by email that would when opened run macro-code to download a second-stage implant, dubbed Rising Sun, which the hackers used to conduct reconnaissance and steal user data.

The Lazarus Group, a hacker group linked to North Korea, was the prime suspect given the overlap with similar code previously used by hackers, but a connection was never confirmed.

Now, McAfee says it’s confident to make the link.

“This was a unique first experience in all my years of threat research and investigations,” said Christiaan Beek, lead scientist and senior principal engineer at McAfee, told TechCrunch in an email. “In having visibility into an adversary’s command-and-control server, we were able to uncover valuable information that lead to more clues to investigate,” he said.

The move was part of an effort to better understand the threat from the nation state, which has in recent years been blamed for the 2016 Sony hack and the WannaCry ransomware outbreak in 2017, as well as more targeted attacks on global businesses.

In the new research seen by TechCrunch out Sunday, the security firm’s examination of the server code revealed Operation Sharpshooter was operational far longer than first believed — dating back to September 2017 — and targeted a broader range of industries and countries, including financial services and critical infrastructure in Europe, the U.K. and the U.S.

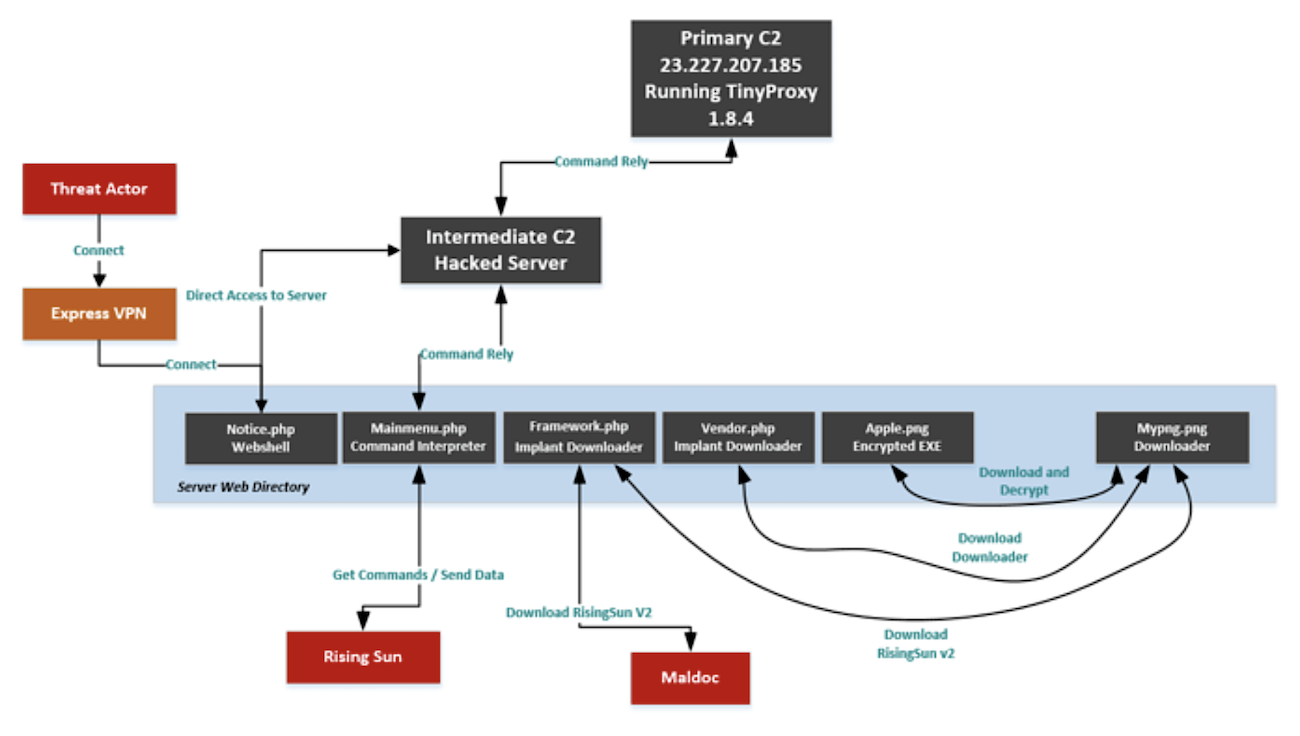

The modular command and control structure of the Rising Sun malware. (Image: McAfee)

The research showed that server, operating as the malware’s command and control infrastructure, was written in the PHP and ASP web languages, used for building websites and web-based applications, making it easily deployed and highly scalable.

The back-end has several components used to launch attacks on the hackers’ targets. Each component has a specific role, such as the implant downloader, which hosts and pulls the implant from another downloader; and the the command interpreter, which operates the Rising Sun implant through an intermediate hacked server to help hide the wider command structure.

The researchers say that the hackers use a factory-style approach to building the Rising Sun, a modular type of malware that was pieced together different components over several years. “These components appear in various implants dating back to 2016, which is one indication that the attacker has access to a set of developed functionalities at their disposal,” said McAfee’s research. The researchers also found a “clear evolutionary” path from Duuzer, a backdoor used to target South Korean computers as far back as 2015, and also part of the same family of malware used in the Sony hack, also attributed to North Korea.

Although the evidence points to the Lazarus Group, evidence from the log files show a batch of IP addresses purportedly from Namibia, which researchers can’t explain.

“It is quite possible that these unobfuscated connections may represent the locations that the adversary is operating from or testing in,” the research said. “Equally, this could be a false flag,” such as an effort to cause confusion in the event that the server is compromised.

The research represents a breakthrough in understanding the adversary behind Operation Sharpshooter. Attribution of cyberattacks is difficult at best, a fact that security researchers and governments alike recognize, given malware authors and threat groups share code and leave red herrings to hide their identities. But obtaining a command and control server, the core innards of a malware campaign, is telling.

Even if the goals of the campaign are still a mystery, McAfee’s chief scientist Raj Samani said the insight will “give us deeper insights in investigations moving forward.”

No comments:

Post a Comment